Second Anniversary Special 4

Setting the Theme

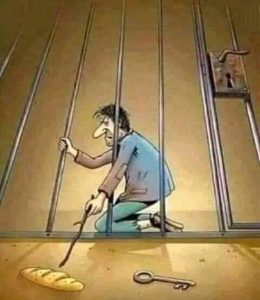

Following the French Revolution health was added to the rights of people and was assumed that health citizenship should be a characteristic of the modern democratic state. Methods for assessing the strength of the state by counting the population became a new state characteristic. Arguably, the human body has been brought twice over into the market: first by people selling their capacity to work, and second, through the intermediary of health. Consequently, the human body enters an economic market as soon as it is susceptible to diseases and health.[1]

In Indian context, with the advent of European medicine, the harnessing of the new medical knowledge to general well being and public service became evident since the foundation of Native Medical Institution (NMI, 1822). What was a medical benevolence of the highly visible earlier sovereign feudal power in India became the new disciplinary power of colonial modernity. It signified a perceptive change in the interplays of state power and their attendant effects on institutions, including medical ones.[2] All these led to the reconstitution of old feudal Indian states to the new emerging nation state.

After the introduction of the Permanent Settlement Act (1793) “many of the older zamindars sold their lands to the new urban commercial elites who had successfully made the transition from Mogul to English rule.”[3] As a result, “the control in the rural area was passing from a Persianized worldview to one that more receptive to English conquerors.”[4] This paradigmatic shift in worldview was quite conducive to the reception of Western medical knowledge, as we shall see shortly. But, to note, the impact of this worldview was limited mostly to the upper echelon of society. Indigenous practitioners were not much affected by this change for a long time (at least till the last quarter of the nineteenth century). This proposition is further strengthened from a report by Meer Ali in 1868 in no other journal than the Indian Medical Gazette – the mouthpiece of Western medical practice in India. He was a lecturer on practice of medicine at the Medical School of Agra. He reported – “In my professional career I have often observed the successful treatment of dysentery by the hakims of Upper India. They often cure the disease simply and effectually by means of aperients, mucilaginous drinks, and light farinaceous food.[5]

At a later period, it became once again evident from a report which made a plea to indigenous practitioners. It was intended that all other competing knowledge systems would be assimilated into and subsumed within one overarching system of Western medical knowledge. If, the report argued, everything goes in uniformity with the prescriptions of this report – “in place of the present double system of medicine practiced in India, we will have Western science engrafted on Eastern customs and requirements, the fusion of the two being far more in accordance with the value and wishes of the people than other systems separately.”[6]

In the parliamentary battle of 1813 the free-traders had stripped the East India Company of its commercial monopoly over India. “Free trade was its solid foundation. Evangelicalism had provided its programme of social reform, its force of character, and its missionary zeal.”[7] Moreover, “Utilitarian hopes of inaugurating a competitive society based on individual rights in the soil, depended as much upon the revenue assessment, and the registration of landholdings which accompanied it, as upon the superstructure of judicial codes and establishments.”[8] Eric Stokes reminds us regarding the year 1818 – As Shelley wrote in that year in his preface to Prometheus Unbound … It was in that year that the orator of the new liberalism, the young Macaulay, shook off his father’s toryism and avowed himself a Radical. It was in the same year that James Mill published his great History of India, and became a candidate for high office in the Company’s Home Government.[9]

All these phenomena taken together led to a situation where Macaulay was backed by the great bulk of Calcutta mercantile community in its fight for English education. It represented to a great extent the permanent Liberal attitude to India. It was the period gestating the formation of semi-modern Indian state. In tandem, changes occurred in education policy – a constituent part of which was medical education. Medical education historically became one of the most productive imperialist networks through which benefits of imperialism could be visible. In England, there were circumstances in which social resentment and political radicalism could flourish; during the 1839s and 1840s a British revolution seemed a real possibility. The social upheavals and ideological currents flowing from the revolution impinged medicine in a variety of ways.[10] The foundation of the University College London (UCL) in 1826 to a great extent influenced the formation and architecture of the CMC. UCL was to become a site at which “crucial issues of orthodox medical knowledge and of the locus of medical authority were contested.”[11] This institution was secular, “infidel” to its detractors, and put emphasis on the importance of basic sciences, and practical experiments. “It did not impose some form of religious test (as in Oxford and Cambridge universities) on those who wished to study there.”[12]

Metaphorically speaking, the first cadaveric dissection (28 October, 1836) had become successful to transform colonial medical anxiety to secular self-confidence. David Hare was quite apprehensive to see the project of the first dissection finally brought about and settled without opposition. A few days before the first dissection, he anxiously asked Madhusudan Gupta – “Do you not know what amount of pain and anxious thoughts you have kept me in for a week almost? … Have you found the text in your shaster authorizing the dissection of dead bodies?”[13] Gupta’s reply was affirmative. He did not fear any opposition. He told Hare, “I and my Pundit friends are prepared to meet them if they come forward which I am sure they will not do.”[14] But, in actual reality, the first demonstration by dissection caused great anxiety in society.[15] The College gates were closed to prevent forcible interruption of that awful act.[16]

Lord William Bentinck had his brief stint in Calcutta from 1828 to 1835. During his rule, he played a key role in the transformation of Indian administrative, educational, tax patterns and, to an extent, social ambience of Calcutta. Bentinck was a Whig in politics. The “avowed” radical Macaulay and liberal James Mill joined him. Macaulay was highly articulate representative of the “West European liberal intelligentsia whom we generally associate with the British Reform of the 1830’s and the revolutions of 1848.”[17] Though the Calcutta mercantile community had its own narrower, more selfish standpoint, Stokes argues, “substantially it swelled the great tide of liberalism engulfing the English mind in the eighteen-thirties.”[18] Importantly, despite the spread of Utilitarian philosophy and Evangelism to an extent, the indigenous cultures of India lingered on in the courts of the princes and pensioners.[19] Bentinck’s later “encouragement of capitalist enterprise in India owed at least as much to … political economy or Benthamism.”[20] In recent scholarship, it is argued that the symbiotic relationship between India’s nascent capitalist and gentry classes and the East India Company started to come under new pressures during the first quarter of the nineteenth century.[21] The shift in relations between British and Indian capital and the transition to a “new capitalist order in India was most closely associated with governorship of Lord William Bentinck.”[22]

These changes and developments in Indian society during the 1830s, when contrasted with Charles Maclean’s monopolist mercantile views in 1813, make one understand the economic and social transition in a better way. Charles Maclean asked the “real and only question” – “What would be the consequences of laying open the navigation to India to private ships?”[23] In his opinion, it might even lead to the commercial bankruptcy. Contrarily, Bentinck is known to have said, “The sooner however that some old-fashioned principles are thrown overboard the better…”[24] Between 1829 and 1835, he transformed a budget deficit of one and a half million pounds sterling into a surplus of half a million pounds. Bayly emphasizes, “It is against this background that Bentinck’s educational reforms must be set.”[25] Moreover, from 1819 new influences were at work at India House “with the appointment of James Mill, the Utilitarian philosopher, as assistant to the Examiner of India correspondence.”[26]

Bentinck reached Calcutta at a time when all these happenings (the strife between the monopolist EIC and the rising Bengali mercantile community advocating for free trade and other issues) “were a matter of lively debate both there and, because of the coming need to renew the company’s Charter at home.”[27] To add, Bentinck had also a copy of Panopticon of Bentham in his possession. Bentham wrote, “While writing, it occurred to me to add a copy of a work Panopticon; the rather because, at the desire of Mr. Mill, it is in the hands of your new Governor-general, Lord William Bentinck…”[28] The famous Panopticon is a historical signifier of the emergence of normalizing disciplinary power (as contrasted with blatant coercive power of pre-modern parochial state) on the one hand, and a sovereign state on the other. Moreover, Bentinck had “indeed subscribed in 1826 for two shares in the newly founded University College, London – an institution under combined Whig, Benthamite and Dissenting control, and a forward battalion in the ‘march of mind’…”.[29]

Another notable change during the period was the introduction of clock-time in everyday life as well as in administrative services. “Disciplinary time was a particularly abrupt and imposed innovation in colonial India. Europe had gone through a much slower and phased transition spanning over some five hundred years: from the first thirteenth- fourteenth-century mechanical … Colonial rule telescoped the entire process for India within one or two generations.”[30] The making of a new kind of individual and, accordingly, the shaping of everyday life was in the offing. CMC facilitated the making of this modern state in so many ways. Bayly informs us, “Physicians were, in addition, important information gatherers for the state.”[31] Those who resided in cities held regular councils and could frame broad calculations of mortality rates by ordering the custodians at the city gates. Thus the profession of medicine as a whole as well as individual medical person was quite intimately tied up with the emergence of modern Indian state.

In a private letter to his friend Peter Auber on 12 March 1834, Bentinck commented, “Three thousand boys are learning English at this moment in Calcutta and the same desire for knowledge is universally spreading…My firm opinion on the country is that no dominion in the world is more secure against internal insurrection…”[32] Interestingly, the passion for acquiring English education provided the state its much desired internal security. Thus modern medical profession and education, which was a part of general education, played a significant role in the making of the state.

Brief Review of Pre-CMC Medicine and Society

In February 1835, a memorial signed by 6,945 Hindu habitants of Calcutta, including all the managers of Hindu college, the parents and guardians of the students of English, was presented to Bentinck praying that the existing restrictions on the use of the English in the law courts be abolished.[33] It signifies that somewhat “universal” acceptance of English as the primary administrative language of the newly emerging modern state was phenomenally palpable. The most important educational feat of Bentinck was the foundation of the CMC. To be sure, CMC had ushered in “hospital medicine” in India, the discussion on which has already been widely discussed in the previous chapters.

How was the medical and health situation in India, especially in Bengal, during the period we are talking about? It was reported, “We have ourselves witnessed many harrowing cases of natives killed outright, solely through the barbarous treatment of the Kabiraj, or village-doctor, who knows far less about curing diseases than an English farrier does; and yet this Eastern type of Dr. Sangrado (a character after Doctor Sangrado, physician, whose panacea was copious bloodletting and drinking of hot water, in the picaresque novel Gil Blas – L’Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane, published between 1715 and 1735 – by Alain René Lesage, French novelist and playwright who died on 1747) requires a fee of one rupee in many cases from poor fellows, who earn only four rupees a month!”[34] This was a space outside the realm of modern state and modern medicine as well in their traditional “dispositif” of living. Hence, to mitigate health and medical problems and, purportedly, to insinuate the tentacles of modern normalizing power, it was suggested at a later period, “a class of pupils to be instructed through the Bengali language (in the CMC), many of whom might be attached to the different thannas.”[35] Thus, medicine which reached even the most interior and remote parts of indigenous social lives attained benevolent face of the modern colonial state. Interestingly, in this process of making Western medicine humane and devoted to the alleviation of sufferings of poor Indian people, the “social” (of indigenous life world) thus becomes tenuously tied to the “state” (unlike the “individual” of modern European state) with the aid of modern Western medicine. Ironically, the “social” was transformed into a new kind of individual when housed in the hospital ward as a “case”.

It was the Act of 1833 in England that injected “fresh vigour into both the Home and Foreign divisions of [the] oriental administration…[and] medical and general education began to experience something like the attention it deserved”.[36] S. Goodeve Chuckerbutty, one of the brightest students of the CMC and the first Indian to excel in the IMS examination, wrote in 1864, “The Kabirajes were ready enough with their nostrums whenever they were required…Of human anatomy they were utterly ignorant; consequently, their surgery was of the rudest kind.”[37] Examples may abound. But the basic fact remains that the state of medicine as a whole was not much laudable before the advent of Western medicine with its institutional practices.

We can have a good account of deplorable medical condition of rural India during the time CMC was founded. Montgomery Martin did extensive surveys of rural Bengal, Bihar and Assam. In the surrounding areas of Rajmahal, he found about “20 Jurrahs, who evacuate the water of hydrocele, treat sores, and draw blood both by cutting a vein, and by a kind of imperfect cupping. They are by birth barbers.”[38] On the contrary, medicine was practiced by Brahmins or Vaidyas or Kayasthas. “Medicine (Baidya-sastra) is taught by several of the pundits, some of whom also, although they grammarians, practice the art.”[39] In Darbhanga, he found some untrained medical men doing their business with herbs. They were variously called as “Atai Baidyas, or doctors defraud the ignorant; Dehati Baidyas, or village doctors; Chasa Baidyas, or plough doctors; Haturya Baidyas, or doctors who attend markets.”[40]

In another area he found 53 Hindus and 4 Mohammedans “profess the art (of medicine)”.[41] Montgomery Martin is possibly the first Company surgeon to talk about, in 1838, what we now know as lathyrism. He observed, “It seems to consist in a weakness and irregular motion of the muscles moving the knees, which are bent and moved with a tremulous irregular motion, somewhat as in the chorea, but not so violent. … It is attributed by some to eating khesari (lathyrus-sativus); but this seems fanciful …”[42] In adjacent areas of Purnea, he found about “150 Jurrahs, or surgeon-barbers, who cup, bleed, and treat sores. The midwives are of the lowest tribes, and merely cut the umbilical cord.”[43] He found that there remained some acts of “hybridization” of European inoculation and Indian variolation. “I have heard that some Europeans have been silly enough to employ them to repeat their spells, even when an European surgeon had performed the operation.”[44] We should note that while the scholastic practice of medicine is vested in the hands of the high caste people, surgical procedures are relegated to the lowest caste and Muslims. The division between medical and surgical practices is quite evident from the big demographic survey done by Martin.

Importantly, Ainslie found Hakeems who possess a great deal of information, and are, “in general, men of polite manners, unassuming, liberal minded and humane.”[45] If those people, living beyond the reach of the modern state, could be brought under the surveillance of local dispensaries and made to learn the techniques modern hygiene, sanitation and other health programs modern state would regain its meaningfulness. Such programs were actively taken by the colonial state. Medicine turned out to be an effective tool in the making of state.

Macleod noted, “With the increase of the armies in the three Presidencies and the increase of factories and stations the medical department increased in numbers.”[46] In 1824, some people of Calcutta wrote to the editor of the Sangbad Coumudy (the Moon of Intelligence), “The people of this country have been relieved from a variety of diseases since it has been in the possession of the English nation.”[47] They wrote that the ten rupees which poor people earned every month was barely sufficient to sustain the family, and, consequently, “the populace have generally not the means of calling in a European doctor…whereby the poor might avail themselves of the medical treatment of European doctors”.[48] They argued, “Were the Hindoo physicians to instruct their children in the knowledge of their own medical Shasters first, and then place them as practitioners under the superintendence of European physicians, it would prove infinitely advantageous to the Natives of the country.”[49]

According to the reporting, this endeavor would benefit the society in four ways. First, pupils would be acquainted with both the English and Bengali mode of learning. Second, “by going to all places, and attending to poor as well as rich families, and to persons of every age and sex, he could render service to all”. Third, “he could go to such places as were inaccessible to European doctors”. Fourth, “this kind of medical knowledge, and the mode of treatment by passing from hand to hand, would be at length spread over the whole country”.[50] The new medicine, heralding its universality with the words “[for] every age and sex”, also incorporated a kind of secular nature into it. To emphasize at this juncture, ontologically speaking, the existing predominant medical practice of the time, Ayurveda, does have unwaveringly male gaze.[51] Bearing only the faint trace of the gurukul system in which knowledge could be passed “from hand to hand”, the English mode of teaching had to be incorporated for better efficacy. It was in such an intellectual climate and bolstered by such favourable social attitudes (at least in a particular section of society) that the NMI struck its deep roots in Bengal.

It was reported, “The demand thus created gradually drew large number of practitioners of European medicine into the villages in the mofussil, and every outbreak of cholera or fever to a noticeable extent in any locality increased their numbers.”[52] From a Foucauldian viewpoint, it may be deduced that the clinical gaze extended from metropolis to the periphery. Indian society experienced the emergence of a new type of medicine which was not only patronized by the state (as was not in case of Ayurveda or Unani) but also actively set it into operation.

Experiments like stipendiary education and, to emphasize, the intertwining of medicine and surgery in one person – one of the hallmarks of “Hospital Medicine: – were effectively practiced in the CMC.

The twin need for an educational economy as well as a cohort of trained “native doctors to supply vacancies in regiments”[53] was the principal motive behind educating ‘native doctors’ in India. In 1855, the Lancet reported, “It is little more than thirty years ago since the wants of the army caused the Medical Boards of Madras and Calcutta to commence instructing natives in some of the simple varieties of medical knowledge”, though these were “of the humblest possible description.”[54] The economic need of the state was explicitly stated: “Native surgeons, educated at the Company’s Medical College in Calcutta, could be easily procured, and would be glad to be employed, at from Rs 25 to Rs 50 per month, with rations and a free passage.”[55] For each English soldier, on the other hand, it would cost the state £100 to train him for duty.[56]

To emphasize, modernity in India was operating in an asymmetrically overdetermined space. The flow of knowledge was always from the centre like London to its recipient periphery Calcutta or Bombay or Madras. For a limited period in the early years of colonialism there were some exchanges of knowledge, but as the colonial state consolidated its power it became a one-way journey.[57] For some concrete examples, it should be mentioned that the way Indian vegetables, minerals and animal products were regarded by earlier authors like Ainslie as “Materia Medica of the Native Indians”[58] was completely reversed after the formation of the CMC. In his “Introductory Address” at the CMC on March 17, 1836, then principal Bramley commented, “there can be no question that your materia medica contains many articles of a fantastic, useless, or destructive character, of which further advance in European Science will point out to you the mischief and danger.”[59] At the same session, Goodeve noted, “Hitherto you are ignorant of the science of materia medica; you know not the names, much less the properties of the various drugs which you are employ in the cure of disease…”[60]

It became widely accepted that “the British government could not have established an institution calculated to be of greater benefit…than the Native Medical Institution [NMI]”.[61] Macaulay’s efforts seemed only to add a snowballing effect to the process already started by the students of the NMI and Calcutta elites taken together. During the decade of its existence, the number of native doctors “which this institution furnished to the public service between 1825 to 1835…was 188”.[62] Eight of the pupils “who had been educated in this seminary were appointed native doctors, and sent with the troops serving in Arracan”.[63]

My contention is that the brief phase of the NMI and the medical classes at the Calcutta Sanskrit College represents the period of gestation of hospital medicine in India. Medical classes at the Sanskrit College started in 1827. But the preparatory phase to introduce pupils to modern science—its technology and technique—had begun earlier. The report of 1828 stated that the progress of the students of the medical classes had been satisfactory “in the study of medicine and anatomy; and particularly that the students had learned to handle human bones without apparent repugnance, and had assisted in the dissection of other animals”.[64] They also “performed the dissection of the softer parts of animals’, and opened ‘little abscesses and dressing sores and cuts”.[65] Moreover, at the Sanskrit College of Calcutta the number of pupils was then 176 and the number was quite impressively increasing. Of these 176, only ninety-nine students received allowances from the college.[66] This estimate makes it clear that seventy-seven students were without allowances and still pursuing their studies at their own expense—the lure of English medical education can be unmistakably discerned from these facts.

The exposure to dead bodies began to erase the social taboo against touching the dead. Before the foundation of the CMC, students were exposed to the postmortem examination through attending clinical classes at the General Hospital. Once again to remember, this act prepared the environs for exposing the new generations of pupils to visual, auditory, verbal and psychological acculturations with the new culture of medicine consistent with the functioning of the new state in the making. Along with these, moral, behavioral and clock-time acculturations were also introduced. These acculturations were of paramount importance as it paved the way for the emerging new medical individual and new citizen as well who would be disseminating new knowledge of the state as well as become its flag bearers.

Hospital Medicine in the Making of Modernity

One of the profound changes brought about by the G.O. No. 28 of 28th January, 1835 (foundation of CMC) was the introduction of secular nature of medical education, not “inferior to some of the most celebrated schools of medicine in Europe”. In 1815, it was reported, “a Brahman boy would not sit down on the same mat with one of another caste.”[67] Within 30 years, people of high and low caste performed together dissection. In 1844-45 session of CMC, there are – “Brahmins, 19; Kaists, 21; Boyddows, 8; Kyburt, 2; Tanty, 2; Bankers, 3; Soory, 1; Talee, 1, Shutgope, 1.” Total number of students was 57.[68] The lectures in CMC, as fully described earlier, started with osteology, leading finally to dissection proper on 28 Oct. 1836. Later on, Medical Jurisprudence and Pathology were added. For better clinical training, two small hospitals – one Male, another Female – were added to the College after 1839. The new kind of midwifery, unlike indigenous one, started since then.

Unlike Europe and UCL (fees ranging from £5 to £20), students were stipendiary here. When stipend was given in CMC, “fee for the Examination” of University of London was £5 (equivalent to Rs.50 at that time), and that of St. Guy’s £20.[69] A mercantile corporation like the EIC invested this amount of stipendiary money not for any gambling out of nothing. It was political economy of education – investment for the generation of desire for European medicine and, consequently, European political hegemony, which led to furtherance of more convincing approval of the British regime as well as the gradual adoption of European medicine and hegemony socially as a token of benevolence.[70]

At the end of 3 and ½ years’ education at CMC – when each candidate had attended 3 courses of anatomy and physiology, 2 of actual dissection, 3 of chemistry, 1 of natural philosophy, 2 of materia medica, 2 of general and medical botany, 2 of practice of physic, 2 of the principles and practice of surgery and 1 of operative surgery – rigorous examinations were taken, lasting from 30 October 1838 to 9 November1838. Finally, 4 outstanding students (out of 11) were declared successful – Umacharan Set, Rajkisto Dey, Dwarakanath Gupta and Nobinchunder Mitter. They were appointed as sub-assistant surgeons in new dispensaries. Dwarakanath did not go into government service and successfully did his private practice in Calcutta.[71] It should be emphasized that within 8 years of the first dissection which was performed with utmost secrecy the situation changed completely. It was openly ruled out – “Every dissecting student shall deposit a sum of two Rupees in the Office of the College, to make good any loss or unnecessary destruction of instruments.”[72]

Along with this, on March 16 1841, it was gleefully noted – “We are happy in being able to report an increasing desire, on the part of the native community, to obtain Medical aid, and in proportion as the purposes of the Dispensaries become known, their advantages will be more and more appreciated.”[73]

Original researches were done in basic sciences – “an amazing total of 557 books and articles with an average of 31 per professor.”[74] In 1845, 4 students made educational sojourn to England to study in UCL. It had three-fold effects – (1) it showed convincingly that Indians could master science and medicine on a level with Europeans; (2) having attained their degrees from the UCL and the Royal College of Surgeons, they served as disseminators of modern science and became role models for future Indian students; (3) their example set the stage for a veritable flood of Indian students to England for study in all fields which continues to this day. They studied under the famous Thomas Graham – the innovator of Graham’s Law in chemistry.

Practitioners required by Government be made available for the different services required and eventually when subordinate seminaries were to be established in different localities it would become an aim that the most promising students may become a professor so that the “College may become a normal Seminary through which individuals capable of conducting schools of Medical Education in different parts of the Country may be provided.”[75]

In 1847, Balfour felt that one of the most striking features was the wonderful success with the opening of Dispensaries. Dispensaries were held by the great majority of the people with increasing favour. They were manned by graduate sub-assistant surgeons of the CMC. Sykes reported “267,456 cases treated”, who were relieved in the Charitable Dispensaries of India in 1847.[76] Arguably, the era of modern public health began to emerge. However, as described in the 4th chapter, in the last months of 1868, on the eve of the opening of the Suez Canal, the freedom of British medical doctors in India to keep purely medical considerations uppermost in mind came to an abrupt end.

Importantly, ether anaesthesia was administered on 22 March 1847, while chloroform was applied on 12 January 1848—within two months after its first introduction in London.[77] Among the prominent points of interest referred to “were the extraordinary success of some of the graduates of the College in the performance of the formidable operation of lithotomy, and the valuable results which had followed the introduction of chloroform into the practice of surgery.”[78] Chloroform was given in two obstetric cases of operative procedure with perfect safety and success in the presence of several of professors, and a number of the students of the CMC.[79]

Harrison, in one of his monographs, concludes thus, “The emergence of what contemporaries celebrated as “rational or “scientific” medicine was therefore intimately bound up with Britain’s commercial and imperial interests, with the empire at home as well as overseas.”[80]

Sometimes there appeared true scientific spirit and rational enquiry suited to colonial soil. W. B. O’Shaughnessy was one of the very few progenitors of such acutely sensitive free scientific mind. But true scientific spirit (except some hands-on training) was subsumed by the Utilitarian leitmotif of the day. And that is undeniably expected when modernity is grafted, not emerging through socio-economic evolution.

The Making of Navya Āyurveda

What may be the most intriguing part of my discussion is the fundamental ontological and epistemological changes carefully wrought into the matrix of Āyurveda, following its encounter or vigorous exchanges with Western medicine. While in the field of materia medica or mineral or botanical knowledge there was some acceptance of Indian medical knowledge till the early 19th century, after the institutionalization of hospital medicine through the CMC it was completely asymmetrically overdetermined. Āyurveda was now at the receiving end only.

Following Meulenbeld, “The renaissance of āyurveda since about the middle of the nineteenth century – historically a fascinating phenomenon – made its protagonists and epigones feel called upon to sketch a profile of this science that would be serviceable in the competitive struggle with Western medicine.”[81] The question arises how this renaissance was brought into becoming and set into motion. Girindranath Mukhopadhyaya, seemingly in contrast to Gananath Sen, notes, “The Sanskrit College was opened on the first day of 1824. This year forms a landmark in the history of education in India.”[82] Sanskrit education in the mold of European or English education appears to be the “landmark”, antedating the date dissection by Hindu students or, supposedly, Madhusudan Gupta. But, according to Mukhopadhyaya, “dissection of the human body” which was “found to be stumbling-block to the progress of the students in Anatomy” was brought to fruition by the Pundit Madhusudan Gupta.[83]

In September 1923, Major R. N. Chopra, Secretary, Ayurvedic Committee, Bengal, sent a set of 17 questions to Mukhopadhyaya, with the intention to modernize Āyurveda. He provided elaborate and very long replies to the questions raised. His replies pithily clinch the question of modernization of Āyurveda, not only copying from English medical texts or incorporating modern medical theories. It dealt with organizational structures and definite programs to make Āyurveda and compatible with the changing modern world of the time. His recommendations included – (a) “Establishment of hospitals for the treatment of patients according to Āyurvedic system”, (b) “Foundation of charitable dispensaries in rural areas”, (c) “Foundation of a scientific library for the use of the students”, (d) “Translation of Sanskrit books and manuscripts into English … for then only can we expect healthy criticism from the savants of the world”, (e) “The text books as read by the students of Āyurveda require to be recast and re-edited to suit our modern conditions of life”.[84] Moreover, he proposed for “Popular lectures dealing with improvements in hygiene and cognate sciences illustrated by lantern slides (today’s power-point presentation), pictures and drawings to elucidate the subject.”[85] He also pleaded for “therapeutic gardens” and “museums”. In his opinion, “The importance of a museum in teaching a scientific subject has been recognized by eminent authorities”.[86] In the Central College, provisions were to be made “for the study of the various sub-divisions of the Āyurveda, namely medicine, surgery, midwifery, children’s disease, pathology, materia medica, anatomy, physiology, hygiene, medical jurisprudence, and the elementary sciences, viz., biology, physics, chemistry, according to the modern scientific methods.”[87]

Girindranath clearly charted a program regarding Tols (traditional centers of Āyurvedic learning). In his opinion, for the time being “the tol system may be retained … the dual system of study may be followed for a time.” But, according to him, “it must however be clearly borne in mind that sooner the Tol system of medical education be stopped, the better.”[88] It sounds like the Greek Oracle of Delphi heralding the doom’s day of Āyurvedic learning in its traditional form. A new hybridized Āyurveda was figured out and set into social motion. Āyurveda was now in the gleeful spirit of mimicry of Western medicine. Girindranath stresses that no medical institution is complete without hospitals – “A complete knowledge of diseases can be acquired in the wards of hospital.”[89] We can understand the deadly impact of modern medicine on Āyurveda. In Āyurveda, patients were always seen in domestic setting – in patient’s own environment. In this new structure of “modernized” Āyurveda patient’s subjectivity would metamorphose into an object of the wards. Moreover, such new phenomena would lead to making the patients into a cohort for statistical analyses, which was completely unthinkable in traditional Indian medical concept. Girindranath strengthens his logical position by citing reference to the Chāndsi doctors who were specialists in ailments related to pile, fissure and fistula-in-ano etc. For him, “the Chāndsi doctors, who still carry a lucrative trade in Calcutta, are in the habit of keeping patients in their own house in a room called by them ‘hospital’ at their own cost, and thus acquire skill in performing certain surgical operations, e.g., piles and fistula-in-ano.”[90] Here Girindranath’s observations pose two distinct questions. First, till the time he mentions Āyurveda was basically a scholastic medicine solely dealing with medical problems and confined to high caste people of the society. Moreover, surgery was taboo to this scholastic medicine and relegated to the low caste people of society. Second, to weave his logic and frame his issue he alludes to the Chandsi doctors who were basically low caste people and somewhat related to Unani system and were looked down upon by Āyurvedic practitioners.

Regarding the functioning and curricula of the Central Āyurvedic College, Girindranath proposed a course of four years. He detailed different subjects to be taught in different years. One must remember the curriculum of the CMC in pre-1845 era. In his proposition, subjects were arranged thus for different years. First-year – physics, chemistry, biology and anatomy, dissection and practical training in scientific subjects. Second-year – anatomy, physiology, materia medica, pathology dissection, practical classes, and hospital duty. Third-year – medicine, surgery, midwifery, hygiene, clinical medicine and surgery, labour cases, hospital duty – medical and surgical, and operative surgery. Fourth-year – same as in the third year, medical jurisprudence and history of medicine. Then he comments, “After a few years, it would be found that a five-year course would cover the subjects better than a course of four years.”[91] At this juncture, it would occur to the reader that it was a virtually a replica of the courses taught at the CMC. Even the transition from four to five years was in mimicry of post-1845 curricular changes in the CMC.

The eternal flow of healing traditions was undermined by the supposed votaries of this tradition itself. It created a kind of “epistemological hypochondria” which led them to vigorously adopting all the means Western medicine, as epitomized in the CMC. Intriguingly, “epistemological hypochondria” in the wider sense of meaning was actually ascribed to the traditional tol system of learning. Girindranath realized that the modern Āyurveda and the tol system would be incompatible. “Tols shall have great difficulty in their practice”, he explains, “So there ought to be a separate system of teachings for those Kavirajes to give them some idea about modern advancements.”[92] Finally, admitting and confining patients into hospitals and dispensaries would facilitate various therapeutic trials.[93] In his words, “Encourage systematic study of diseases and drugs according to Ayurvedic and if necessary modern methods.”[94] The adoption of modern scientific methods, “where necessary for the said purpose and is not based on blind orthodoxy”[95], were also quite expectedly emphasized by him.

To be sure, here I am not on the judgmental seat to give verdict whether this process was conducive or not to the revival of Āyurvedic learning. But it can be safely said that the rise of hospital medicine in India was instrumental in the total reconstruction of Āyurveda in both epistemological and ontological matrices. In this way the reconstruction of Āyurveda was a definite entity and force in the making of modern Indian state. To be put otherwise, modern Indian state became successful to reorient Āyurvedic learning to suit its purposes.

[1] Michel Foucault, “The Crisis of Medicine or the Crisis of Antimedicine?” Foucault Studies 1 (2004): 5-19 (16).

[2] For a fuller study on NMI and CMC and the genesis of hospital medicine in India see, Jayanta Bhattacharya, “The genesis of hospital medicine in India: The Calcutta Medical College (CMC) and the emergence of a new medical epistemology,” Indian Economic and Social History Review 51.2 (2014): 231-264.

[3] Joseph E. Di Bona, “Indigenous Virtue and Foreign Vice: Alternative Perspective on Colonial Education,” Comparative Education Review 25.2 (1981): 202-215 (212).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Meer Ushraf Ali, “Treatment of Dysentery by Native Medicines,” Indian Medical Gazette 3.1 (1868): 83-84 (83).

[6] Anonymous, “A Plea for Hakeems,” Indian Medical Gazette 3.1 (1868): 87-89 (89).

[7] Eric Stokes, The English Utilitarians and India (London: Oxford University Press, 1959), xiv.

[8] Ibid, 81.

[9] Ibid, xvi.

[10] Stephen Jacyna, “Medicine in transformation, 1800-1849,” in The Western Medical Tradition: 1800 to 2000, W. F. Bynum, Anne Hardy, Stephen Jacyna, Christopher Lawrence, E. M. (Tili) Tansey (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 11-110.

[11] Ibid, 21.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Peary Chand Mittra, A Biographical Sketch of David Hare (Calcutta: W. Newman & Co., 1877), p. 138

[14] Ibid, pp. 138-139.

[15] Though in general accounts Madhusudan Gupta has been accepted as the first dissector, it can be contested. See, Jayanta Bhattacharya, “The first dissection controversy: the introduction to anatomical education in Bengal and British India,” Current Science 101.9 (2011): 1227-1232.

[16] Pramatha Nath Bose, A History of Hindu Civilisation during British Rule, Vol. II (Calcutta: W. Newman & Co., 1894), p. 32.

[17] David Kopf, British Orientalism and the Bengal Renaissance: The Dynamics of Indian Modernization 1773-1835 (Calcutta: Firma K. L. Mukhopadhyay, 1969), 143.

[18] Stokes, English Utilitarians, p. 43.

[19] Stokes, “The First Century of British Colonial Rule in India: Social Revolution or Social Stagnation?,” in Modern India, 173-198.

[20] John Rosselli, Lord William Bentinck: The Making of a Liberal Imperialist (Berkley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1974), 87. Also see, Demetrius C. Bougler, Lord William Bentinck (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1892).

[21] Burton Stein, A History of India (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2004), 220.

[22] Ibid, p. 221.

[23] Charles Maclean, Abstract of the East India Question: illustrating in a concrete manner the controversy between the East India Company and His Majesty’s ministers (London: J. Mawman, 1813), 3.

[24] Rosselli, William Bentinck, p. 187.

[25] C. A. Bayly, Indian society and the making of British Empire (Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 121.

[26] A. F. Salahuddin Ahmed, Social Ideas and Social Change in Bengal 1818-1835, Papyrus edition (Calcutta: Papyrus, 2003), 189.

[27] Rosselli, Bentinck, p. 185.

[28] The Works of Jeremy Bentham, ed. John Bowring, vol. 10 (Edinburgh, 1843), 591.

[29] Rosselli, Bentinck, p. 85.

[30] Sumit Sarkar, Writing Social History (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2002), 309.

[31] C. A. Bayly, Empire and Information: Intelligence gathering and social communication in India, 1780-1870 (New Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 265.

[32] The Correspondence of Lord William Cavendish Bentinck: Governor General of India 1828-1835, ed. C. H. Philips, in 2 volumes, vol. II (London: Oxford University Press, 1977), 1279-1280. [Emphasis added]

[33] Ahmed, Social Ideas, p. 204.

[34] Anonymous, “Miscellaneous Critical Notices,” Calcutta Review 13.25 (1850): xix. [Emphasis added]

[35] Anonymous, “Vernacular Education for Bengal,” Calcutta Review 22.44 (1854): 328.

[36] Anonymous, “Sketch of an Indian Physician,” Lancet 1 (1855): 48.

[37] S. Goodeve Chuckerbutty, Popular Lectures on Subjects of Indian Interest (Calcutta: Thomas S. Smith, 1870), 139.

[38] Martin, The History, Antiquities, Topography, and Statistics of Eastern India; Containing the Districts of Behar, Shahabad, Bhagalpoor, Goruckpoor, Dinajepoor, Puraniya, Rungpoor, and Assam, in 3 volumes, vol. II (London: Wm. H. Allen and Co., 1838), 106. [Emphasis added]

[39] Martin, History, Antiquities, Topography, vol. I, p. 137.

[40] Martin, History, Antiquities, Topography, vol. III, p. 142

[41] Ibid, p. 510.

[42] Montgomery Martin, The History, Antiquities, Topography, and Statistics of Eastern India, vol. I (London: Wm. H. Allen and Co., 1838), 115.

[43] Ibid, p. 139.

[44] Ibid, p. 140.

[45] Whitelaw Ainslie, Materia Indica, vol. II (London: Longman, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1826), xxxiii.

[46] Kenneth Macleod, “The Introduction and Spread of Western Medical Science in India,” Calcutta Review 71 (1914): 419-454 (432).

[47] Anonymous, “Miscellaneous – Bengally Newspapers,” Asiatic Journal 14.82 (October 1822): 385-390.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Ibid, p. 388.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Dominik Wujastyk, The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from the Ayurvedic Classics (New Delhi: Penguin Books, 1998), 23.

[52] Calcutta Journal of Medicine VII (Nos. 10-12, 1874): 380.

[53] Anonymous, “Education of Native Doctors,” Asiatic Journal 22.127 (1826): 111-121.

[54] Anonymous, “Sketch of an Indian Physician,” Lancet I (1855): 48.

[55] Report of the Select Committee on Transportation; Together with the Minutes of Evidence, Appendix and Index (London, 1838), 196.

[56] W. J. Moore, Health in the Tropics or Sanitary Art Applied to Europeans in India (London: John Churchill, 1862), 6.

[57] For discussion at length on this issue see, Michael Adas, Machine as the Measure of Men: Science, Technology, and the Ideologies of Western Dominance (Ithaca, London: Cornell University Press, 1989); M. N. Pearson, “The Thin Edge of the Wedge: Medical Relativities as a Paradigm of Early Modern Indo-European Relations,” Modern Asian Studies 29,1 (1995): 141-170.

[58] Whitelaw Ainslie, Materia Medica of Hindoostan (Madras: Government Press, 1813); Ainslie,

[59] M. J. Bramley, “Introductory Address Delivered at the Opening of the Calcutta Medical College,” Calcutta Monthly Journal and General Register of Occurrences, Third Series: Vol. II (May 1836): 1-7 (6). [Emphasis added]

[60] H. H. Goodeve, “Practice of Physic,” Calcutta Monthly Journal, Third Series: Vol. II (May 1836): 19-26 (25). [Emphasis added]

[61] Anonymous, “Liberality of the Indian Government towards the Native Medical Institution,” Oriental Herald X.31 (1826):17–25.

[62] The Centenary of the Medical College Bengal, 1835-1934 (1935), 9.

[63] Minutes of Evidence taken before the Select Committee on the Affairs of the East India Company, I. Public (London, 1832), 448.

[64] Anonymous, “Native Medical Society,” Asiatic Journal, New Series, 7.26 (1832): 84–85.

[65] Kopf, British Orientalism, 183-184.

[66] Minutes of Evidence, 494.

[67] Adam’s Report on Vernacular Education (Calcutta: Home Secretariat Press, 1868), 3.

[68] General Report on Public Instruction, 1844-45, 98.

[69] “Account of the Hospitals and Schools of Medicine in London,” Lancet vol. I (1841-42): 3-20.

[70] Charles Trevelyan, On Education of the People of India (London: Longman, Orme, 1838).

[71] GCPI (1839).

[72] Rules and Regulations of Bengal Medical College, 1844, p. 33.

[73] GCPI 1841, Appendix, No. VII, p. clxxiii.

[74] Mel Groman, “Introduction of Western Science in Colonial India”, p. 293.

[75] Selections from Educational Records, Part II, 1840-1859, Ed. J. A. Richey (Calcutta, 1923), 322.

[76] W. H. Sykes, “Statistics of the Government Charitable Dispensaries of India, chiefly in the Bengal and North-Western Provinces,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society X (1947): 3.

[77] S. Anantha Pillai, Understanding Anaesthesia (New Delhi, 2007), 13.

[78] GRPI 1851, p. 122.

[79] GRPI 1848, Appendix E, No. VIII, p. cli.

[80] Mark Harrison, Medicine in an Age of Commerce and Empire: Britain and its Tropical Colonies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 291.

[81] Meulenbeld, HIML, 1A, p. 2. This issue has been fragmentarily discussed in the 1st chapter.

[82] Girindranath Mukhopadhyaya, History of Indian Medicine, 2nd edn., 2 volumes, vol. 2 (New Delhi: Orient Books Reprint Corporation, 1974), pp. 14-15.

[83] Ibid, p. 17.

[84] Ibid, p. 22. [Emphasis added. All these characteristics reproduced from within Āyurveda remind the readers of the beginning of the CMC and the rise of hospital medicine in India]

[85] Ibid, p. 23. The mention of lantern slides leads us to believe the employment of modern technology, which is now developed in the form of power-point presentation (ppt).

[86] Ibid, p. 23.

[87] Ibid, pp. 23-24.

[88] Ibid, 24.

[89] Ibid, 25.

[90] Ibid.

[91] Ibid, 26.

[92] Mukhopadhyaya, History of Indian Medicine, vol. 2, p. 5051.

[93] Ibid, pp. 52-53.

[94] Ibid, p. 53.

[95] Ibid, p. 77.

Bold and beautiful

Dear Dr Jayanta — to day is 26th.Dec.of dying year of 2021. However it is a day of exchange of pleasantries — in words or kinds, amongst the people you like or consonant with mind game . Your article — titled ” The Calcutta Medical College (CMC), ‘Modern’ India and Navya Ayurveda ” — posted late last night arrived to me as a “BOXING DAY”gift to be preserved with care for many readings in days and months to come. Its logical algorithm , style of composition,semiotic and quality of English is of International academic lucre.You must send the copies of it to — Dominik, Dagmer, Rahul,Pratik of M’chester and many such scholars in this field of colonial and post modern historical Indology. I have no doubt it would be lapped up by any famous journal of serious intellectual intents. It is marvelous. Bon Voyage in your attempt to international literary voyaging.. It is highly IMPERATIVE —- n.da

My gratitude ?

This is most brilliant work of Dr Byattacharya. It must be evaluated with proper respect.

I am grateful to doctorsdialogue platform to share such a rich article by Dr Jayanta Bhattacharya. I had an impression from my association with health system as a generalist that Ayurveda, Homeopathy and hekimi methods of treatments are still faithfully acceptable to a good many people all over India though the gurus of these systems had initially tried to block their systems in an organised way so that they can retain their respective identities during the “English” medical system. As such their systems could not grow after a certain stage as they did not like to take the advantage of the progress of the new systems. After a certain point of time they realised their mistake and started to adjust with the new system and upgrade their systems. British Government tried to encourage them at a later stage and the independent Indian government also is trying to encourage them through a department, AYUSH.

Dr Bhattacharya has nicely deliberated on these issues in a convincing way with necessary documentation. I would like to thank him.

Thank you!