The first cholera morbus (to differentiate it from common or English cholera) patient William Sproat was detected in Sunderland on 20 October 1831. It spread like a hellfire and cuased deaths of thousands of people without any treatment.[1] It was the year when a young Edinburgh M.D. of just 22 years of age arrived in London and immediately became intersed to find the cause of this fatal disease. He was William Brooke O’Shaughnessy (1809-1889). History provides us with three names of this illustrious youth – William Sands, William Brooke O’Shaughnessy and O’Shaugnesy Brooke since 1861.[2] To mention, in the 1830s about 60% of doctors of East India Company were Edinburgh graduates.

Source: Reproduced from Medical Reporter, Calcutta, 5, 204 (1895)

When O’Shaughnessy was born in the year 1809, two more history-changing personalities were also born in the same year – Charles Darwin in UK and Abrham Lincoln in US. It signifies that it was the period when new thoughts were coming up. It is interesting to note, O’Shaughnessy’s career reflected the diversity of training that he received while studying medicine at Edinburgh University. The Scottish Enlightenment and the influence of Common Sense philosophy in Scottish educational institutions saw the syllabi, including the science curriculum, adopt a holistic approach: all aspects of philosophical debate were combined with a detailed knowledge of the body, and of physics and chemistry.[3] It can be safely said that O’Shuaghnessy started his medical career as a forensic chemist.[4]

He was equally interested in theoretical and experimental chemistry, physics, medical toxicology, in the discovery of newer drugs, first international medical use of cannabis, discovery of ‘narcotine’ – an opium derivative – to replace Peruvian bark or quinine which was costly for the use of poor Indian people, experiments with mineriology and so on and, also, telegraph too.

Moreover, on behalf of the Central Board of Health, London, he published a book on on chemical pathology of malignant malaria.[5] He prescribed some provisional “treatment of the fever stage” by which he expected “much benefit from the frequently repeated use of the beutral salts by the mouth or by enemata”. He proposed the following compositon: “Phosphate of Soda – ten grains. Muriate of Soda – ten grains. Carbonate of Soda – five grains. Sulphate of Soda – ten grains. Dissolve in six ounces of water. The mixture to be repeated every second hour.”[6]

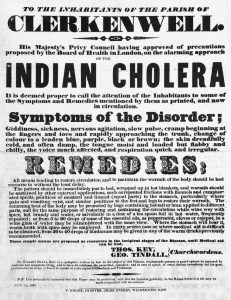

The disease was referred to as Cholera Morbus in order to distinguish it from common or English cholera, dysentery and food poisoning that were already common in the UK, particularly during warm weather. These diseases are now more commonly referred to as gastroenteritis. In the early years there was considerable confusion between the two diseases. The first confirmed case was that of William Sproat, a keelman who lived near the quayside, Sunderland. He fell ill on 23 October, and died after three days. The disease spread like a hellish fire and In Britain, 32,000 people died of cholera in 1831 and 1832.[7]

(Broadsheet warning about Indian cholera 1831. Source: Wellcome Collection)

Going against the miasmatic theory of disease of the time he published his important research paper on cholera in the radical journal Lancet.[8] It was published on 3 December 1831, less than two months after the detection of the first case of cholera.

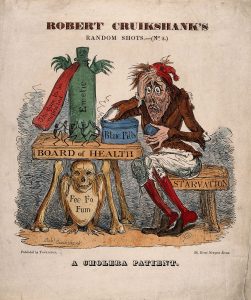

It is tempting to mention here the state of cholera treatment of the time. To be sure, there was nothing definitive and everything was based on dictated mainly by miasmatic origin of the disease.

(Coping with Cholera. Source: The National Archives)

On 3 December 1831, William O’Shaughnessy read a paper before the Westminster Medical Society in which he proposed the intravenous injection of “highly-oxygenised salts” (potassium nitrate or chlorat ) as an alternative means of restoring the arterial qualities of the blood in cases where venesection proved impossible, or “the violence of the malady derides all others means of medication”.

In his paper O’Shaugnessy’s observation was ‘in the briefest time I can employ, an outline of suggestions regarding the treatment of the Indian cholera … foundation of the subsequent observations is also strictly experimental and demonstrable in its nature.’ He further studied with his results and rectified his ideas. In his leter to the editor of Lancet on 19 December 1831 elaborated it –

“1. The blood drawn in the worst cases of the cholera is unchanged in its anatomical or globular structure. 2. It has lost a large proportion of its water, 1000 parts of cholera serum having but the average of 860 parts of water. 3. It has lost also a great proportion of its NEUTRAL saline ingredients. 4. Of the free alkali contained in healthy serum, not a particle is present in some cholera cases, and barely a trace in others. 5. Urea exists in the cases where suppression of urine has been a marked symptom. 6. All the salts deficient in the blood, especially the carbonate of soda, are present in large quantities in the peculiar white dejected matters. … All my experiments, however, have been publicly performed, and can be authenticated by numerous witnesses…”[9]

The nature of cholera was revealed to make a ‘pradign shift’ in the perception of the disease. Interestingly, O’Shaughnessy did animal experiment on dog, not in human being. Dr. Thomas Latta materialized it by application on human being. It was 10 May 1832 – a cornerstone in medical discovery. O’Shuaghnessy admitted, “I beg to state that the results of the practice described by Drs. Latta and Lewins exceed my most sanguine anticipations.” But every endeavour and discovery ended in a big vacuum – “The death of Thomas Latta in 1833, and the departure of O’Shaughnessy to India in August of that year, effectively ended research into the treatment of cholera and the chemical pathology of the blood in cholera victims.”[10]

O’Shaughnessy’s contribution to original scientific researches and advancement is more scientifically and meticulously described by another researcher, “In that year, O’Shaughnessy joined the East India Company and went to India. There he interested himself, not with cholera, but with chemistry, electricity, and telegraphy. He was knighted in 1856, not for work in medicine, but for establishing a telegraph service between the main centres of India which was said to have influenced the result of the Indian mutiny. William O’Shaughnessy’s third claim to fame was that, on returning from India, he introduced cannabis to England and Europe as a potent medication and analgesic for the treatment of tetanus, rheumatism, and epilepsy. He died in 1889, but obituary notices make no mention of his pioneering research – his analyses of the blood and excreta of cholera patients, his deduction of the mechanism of the changes in composition, and his proposal of rational treatment, which was put into practice by Thomas Latta and Robert Lewins of Leith. All this when O’Shaughnessy was 22 and 23 years old, and when chemical pathology was an embryonic science.”[11]

It important to note here that even so-called “metropolitan” science could not assay the depth and extent of his work. It is not some phenomena to boast of.

O’Shaughnessy in India and at CMC

When he came to India in 1833 he had the rank of assistant surgeon. Then elevated to surgeon and, subsequently, to surgeon major rank. O’Shaughnessy soon became second in-charge of the Calcutta Mint. The mint produced and converted coins; Pagodas, a currency common in southern regions of India and other currencies coming into the mint had to be tested for levels of purity before conversion.

His scientific inquiries were as alive as was in England. As assistant surgeon posted in Gaya, Bihar, he published a new research paper.[12] To my analysis, he most likely gave some early hints of kala-azar body in the blood – “The existence of a previously unknown principle in the specimen of blood then before me, having thus unequivocally ascertained, several interesting questions immediately arose.”[13] Known to almost everyone, Calcutta Medical College (CMC) or Bengal Medical College or Medical College, Bengal or the New Medical College (variously termed) was founded on 28 January 1835 – “the foundation of the Medical College, from 1st Feb., 1835, was sanctioned in G.O. No. 28 of 28th Jan., 1835, the Native Medical Institution and the medical classes at the Madrasa and at the Sanskrit College being abolished.”[14] CMC started rather unassminngly with only two teachers – M. J. Bramley as the Principal and H. H. Goodeve as his assistant. “By G.O. No. 10 of 5th Aug., 1835, Bramley’s ofiicial designation was changed from Supt. to Principal, that of Goodeve from Assistant to the Supt. to Professor of Medicine and Anatomy; while a Professor of Materia Medica and Chemistry was added to the staff, Assistant Surgeon W. B. O’Shaughnessy.”[15]

In its initial period, CMC had no textbook for students, no structured syllabi. Only the 39-clause G.O. made it obvious that period of studentship should not be less than four years and not more six years. “Henry Goodeve and William O’Shaughnessy proclaimed that as teachers in a new project they built their courses of study from the contents of British and foreign journals. Of the seventeen medical journals they used, nine were French and eight British.”[16] As teachers, Goodeve and O’Shaughnessy were earnest enough to keep them on track with the metropolitan medical developments – “It must not be said of us in Europe, that expatriation has rendered us inefficient in the advancement of our profession. We will rather strive to excite among our brethren of the fatherland some surprise, that amidst the many impediments which beset us here, we still pursue with unabated zeal the various useful and ennobling branches of our truly philanthropic art.”[17] They tried best to put the CMC in the global network of science.

Gorman points out an important fact about O’Shaughnessy’s chemistry classes – “At a time when a chemical laboratory in an American medical school was rare, this course with lectures and laboratory work was the equal of any in a European medical institution.”[18] Elsewhere, Gorman notes, “O’Shaughnessy’s role in the transmission of forensic chemistry to India is well illustrated by his recognition of the medico-legal value of the Marsh test for the detection of arsenic. Early in 1836 James Marsh of the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, published his procedure for the detection of arsenic by the conver-sion of its compounds to arsine (AsH3) and subsequent decomposition to ele-mental arsenic. Contemporary chemists regarded this test as epoch-making, and it initiated a flurry of excitement and interest which did not subside for years.”[19] As a teacher of CMC, O’Shaughnessy may be regarded as the father of medical toxicology (later known as forensic medicine). As Gorman further points out, “Some insight into O’Shaughnessy’s activities as chemical examiner can be gleaned from a year’s report on various poisoning cases within the year following April I840. Magistrates from all over British India sent powders, fluids, and stomach contents for analysis. Arsenic cases were the major category, including the trioxide and the trisulphide.”[20]

Experiments and O’Shaughnessy

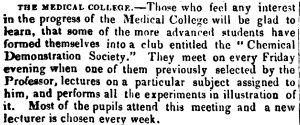

O’Shaughnesy infused such a strong spirit of inquiry among his students tha even formed a “Chemical Demonstration Society” in Calcutta, first ever such society in India.

Importantly, O’Shaughnessy also became secretary par interim of the Asiatic Society, along with Malan of Bishop’s College, when the indefatigable secretary James Prinsep became ill for a long time and went to London for the restoration of his health.[21]

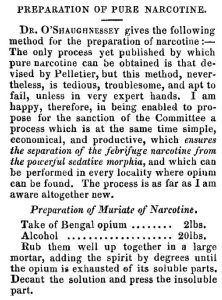

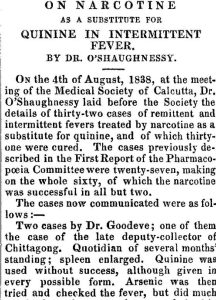

In 1839, the import of Peruvian bark (source of quinine) was stopped by Peru governmemt. To alleviate sufferings of millions of poor Indian people he discovered a new substitute “narcotine” (muriate of opium), the report of which was published in Lancet.[22] Besides narcotine’s use in intermittent fever or malaria, an American journal reported, narcotine was also used in ague – “Dr. O’Shaughnessy added that, besides the sixty cases now recorded, more than 100 ague patients had been treated by his pupils and acquaintance with perfect success by this remedy.”[23] It was later renamed “anorcotine”.[24] According to Lancet, “It is generally known, that one of the crystalline constituents of opium received from chemists the name of “narcotine,” under an erroneous impression that it was the narcotic principle of that drug.”[25] Lancet added, “it is very properly proposed to prefix the privative letter a to the name, and henceforth designate it as anarcotine.”[26]

He did extensive experiments on Indian hemp[27] and he was the first scientist to introduce the medical use of Indian hemp to the western world. Thus “colonial science” went international. Crosbie observes, “In the mid nineteenth century cannabis was virtually unknown as a drug in Europe and North America. Within a few years of O’Shaughnessy’s experiments, however, it was being used as a medication to treat a wide range of conditions by many of the leading doctors in Ireland, including Robert Graves and Sir Philip Crampton in Dublin.”[28]

Some very interesting characteristics associated with his experiments with Indian hemp or Gunjah: (1) To my knowledge, in the medical history of Indian drugs O’Shaughnessy did the first animal trial on dog at different concentrations before applying it on human being,[29] (2) “Encouraged by these results … an extensive trial” on humans was done,[30] (3) he applied the drug in cases of rheumatism, catalepsy, hydrophobia, cholera, tetanus, infantile convulsions, delirium tremens,[31] (4) he was possibly the first person to use “informed consent” for a trial of Indian hemp on an infant of fory days only – “I stated to the parents the results of the experiments I had made with the hemp … that it would relieve their infant if relief could possibly be obtained. They gladly consented to the trial…”[32]

Out of his classes on electromagnetism and galavanism, in 1837, he published his book.[33] This book startled an American journal – “It would have been natural to expect from Calcutta a case of indigo or of gum shellac, rather than a pamphlet upon a matter of science.”[34]

Besides these achievements more of his works include – “Lectures on General Chemistry and Natural Philosophy,” India Journal of Medical and Physical Science – New Series, 1836, Vol. 1 (1): 225-232. Manual of Chemistry, Arranged for Native, General and Medical Students, and the Subordinate Medical Department of the Service, 2nd edn, (Calcutta: Ostell and Lepage, 1842), The Bengal Dispensatory and Pharmacopeia (Calcutta: Bishop’s College Press, 1841).

Concluding Remarks

A few interesting facts may end up this little journey on a very big scientist. Interestingly, he was even requested by government to assess the impact of lightning in Calcutta, which included Dr. Goodeve’s house at the Park Street.[35]

Between 1834 and 1837 there was a race for the patenting of the best telegraphic device. Morse, O’Shaughnessy, Wheatstone and others were inventing separate versions of telegraphy and were harnessing electricity for different purposes. O’Shaughnessy joined this race but had no right to patent any device not constructed in Britain.[36] His use of original methods and local resources were completely ignored because of his endeavour in a colony.

He made innumerable experiments on iron and copper wire ropes insulated in various ways and protected by spiral or parallel guards of iron wire and rods, and it was not until after many failures that he adopted the chain cable idea. He appears to have used generally gutta-percha covered copper wire 1/16 inch in diameter, which was protected from the chemical action of the water by a coating of sheet lead put on in spirals and secured with a spiral of tape saturated with melted wax applied hot. In 1852, the two most important cables in circuit were those across the Huldee and Hooghly rivers. The former was 4,200 feet in length and the latter was 6,200 feet. This may be taken as the first system of telegraphs in India, for later on in the same report he says that the offices were opened for actual business on the 4th October 1851.[37]

________________________

[1] E. Ashwrth Underwood, ‘The History of Cholera in Graet Britain,’ Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 1948, XLV (165): 165-173.

[2] D. G. Crawford, Roll of the Indian Medical Service, 1615-1930, vol. 1 (London: W. Thacker & Co., 1930), 106 (entry 1232).

[3] C. M. Shepaherd, ‘Philosophy and Science in the Arts Curriculum of the Scottish Universities in the Seventeenth Century’, unpublished Ph.D. diss., Edinburgh University, 1975.

[4] Mel Gorman, ‘Sir William Brooke O’Shaughnessy, FRS (1809-1889), Alnglo-Indian Forensic Chemist,’ Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 1984, 39 (1): 51-64.

[5] W. B. O’Shaughnessy, Report on the Chemical Pathology of the Malignant Cholera (London: S. Highlie, 1832).

[6] Ibid., 54.

[7] UK Paliament Report, https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/towns/tyne-and-wear-case-study/introduction/cholera-in-sunderland/ (accessed 3 July 2021)

[8] W. B. O’Shaughnessy, “Proposal of a Kind of Treating the Blue Epidemic Cholera by the Injection of Highly-Oxygenated Salt into the Venous System,” Lancet 1 (1831-32): 366-371. Some other important papers of O’Shaughnessy include – “Experiments on the Blood in Cholera,” Lancet 1831, 17 (435): 490; “On the Blood in the Cholera,” Lancet 1833, 19 (495): 704.

[9] O’Shaughnessy, “Experiments on the Blood in Cholera,” Lancet 1831, 17 (435): 490. Also see, W. E. van Heyningen and John R. Seal, Cholera: The American Scientific Experience, 1947-1980 (London, New York: Routledge), 21-23.

[10] N. MacGillivary, ‘Dr. Latta of Leith: pioneer in the treatment of cholera by intravenous saline infusion,’ J R Coll Physians Edinb 2006, 36: 8-85.

[11] J. E. Consett, ‘The Origins of Intravenous Fluid Therapy,’ Lancet 1989, 333 (8641): 768-771.

[12] W. B. O’Shaughnessy, ‘Discovery of a New Principle (Sub-rubrine) in Human Blood, in Health and Disease, and also in the Blood of Several of the Lower Mamalia,’ Lancet 1835, 23 (597): 677-679.

[13] Ibd., 678.

[14] D. G. Crawford, A History of Indian Medical Service, 1600-1913, vol. 2 (London: W. Thacker & Co., 1914), 435.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Mel Gorman, ‘Introduction of Western Science into Colonial India: Role of the Calcutta Medical College,’ Proceedings of American Philosophical Society 1988, 132 (3): 296.

[17] ‘The Quarterly Journal of the Calcutta Medical and Physical Society,’ Calcutta Monthly Journal for the Month of Januray 1837 1838, (XXVI): 16.

[18] Gorman, idem, 287.

[19] Gorman, ‘’Sir William Brooke O’Shaughnessy,’ 58.

[20] Ibid., 60.

[21] ‘Supplement to Asiatic Intelligence,’ Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register (New Series) February 1839, 28 (110): 121.

[22] O’Shaughnessy, ‘On narcotine as a substitute of intermittent fever,’ Lancet 1839, 32 (829): 606-607.

[23] ‘On Narcotine as a substitute for Quinine in Intermittent Fevers’, p. 195. The Journal “substituted” WB O’Shaughnessy as R. O’Shaughnessy!

[24] ‘Anarcotine’, pp. 53-54.

[25] Ibid., 53.

[26] Ibid. [Italics in original]

[27] O’Shaughnessy, On the preparation of Indian hemp, or Gunjah (Cannabis india): their effects on animal system on health, and their utility in treatment of tetanus and other convulsive diseases (London, publisher not identified, 1843).

[28] Barry Crosbie, Irish Imperial Networks: Migration, Social Communication and Exchange in Nineteenth-Century India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 184.

[29] O’Shaughnessy, On the preparation of Indian hemp, or Gunjah, 18-19.

[30] Ibd., 19.

[31] Ibid., 20-34.

[32] Ibid., 32.

[33] O’Shaughnessy, On the Employment of the Electro-Magnet as a Moving Power; with a Description of a Model Machine worked by this Agent (Calcutta, 1837).

[34] “O’Shaughnessy on Electro-Magnetism,” North American Review 1837, 45 (97): 495.

[35] “Official correspondence on the attaching of Lightning Conductors to Powder Magazines. Communicated by permission of Government, by W. B. O’SHAUGHNESSY, Assistant Surgeon, Bengal Medical Service,” Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal January-June 1840, IX (Pt. I): 277-284.

[36] Deep Kanta Lahiri Chowdhury, Telegraphic Imperialism: Crisis and Panic in the Indian Empire, c. 1830-1920 (Hampshire: Palgarve Macmillan, 2010), 18.

[37] M. Adams, Memoir of Surgeon-Major Sir W. O’Shaughnessy Brooke, Kt. I Connection with the Early History of the Telegraph in India (Simla: Government Central; Printing Press, 1889), 11-13.

Very nice your write 🙏🙏🙏

অনেক ধন্যবাদ স্যার. Information টা share করার জন্য

Very informative. 🙏🙏

Congratulations on penning these interesting and revealing facts. You have shown how O Shaugnessy introduced Canabis to the Western population. Now, it will be probably Re-introduced to India as the “processed,refined and hygienic European Canabis”. The drug industry too may pick it up with lobbying for complete destruction of the Indian varieties. Good analysis, Dr Bhattacharya. Please carry on with your thought provoking and highly informative writings.