Doctor-patient dynamics

The third parallel workshop in the post-lunch session was on the theme of ‘Methods and tools for generating knowledge’. The first presenter described an interesting experiment, where researchers were asked whether the patient’s level of knowledge or voice makes any difference to the way medicines are prescribed. As part of the undercover study standardized patients (SPs) visited 227 private health facilities in Tanzania to seek care. The SPs were trained to present a case of uncomplicated upper respiratory tract infection, with symptoms of a cough, sore throat and headache lasting three days. SPs were randomized to ‘informed’ or ‘uninformed’ roles; informed SPs made a statement that they had heard antibiotics were not necessary for a simple cough, and uninformed patients made no statement.

The study found there was an extremely high rate of antibiotic over-prescription, with over 90% receiving an unnecessary prescription. Patients who signaled knowledge of correct antibiotic prescription practices were less likely to be prescribed an antibiotic – but very slightly (from 94% to 86%). However, signaling this knowledge did not reduce overall prescription rates of any drug, mean number of drugs prescribed or mean expenditure.

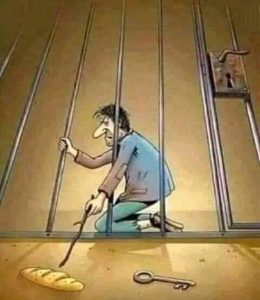

Listening to them, Sholmes had wondered why was there such a big differential between the power of the doctor and their patients? Had this always been the case or had it increased due to the growing specialisation of knowledge and the world of medicine becoming far more complex than in ancient times? What really would be needed to change the supreme confidence with which physicians hand out pills like candies to their patients? Or prevent patients from accepting these pills meekly without questioning?

As he recollected all this Sholmes felt his blood pressure rising and had some quite violent thoughts brewing in his head. Spotting a painting of Lord Buddha, in a calm meditative pose in a corner of the room he calmed down but decided to get out for some fresh air.

He couldn’t get the subject out of his mind though. Why was the patient’s right to know and decide on the course of treatment so easily brushed aside by professionals in certain cultures and contexts? Was it even possible for individual patients to learn and decide on complex medical issues all on their own?

Was there some way by which these currently academic tools and methods could be simplified in a way that ordinary patients or communities could use them to improve usage of medicines? Was it possible to list out the broad principles that everyone should be aware of while prescribing medicines or being prescribed to?

It had been a tiring day and given the delicate condition of Whatsup’s stomach the duo decided to go to bed early. They missed sitting alongside the Chao Phraya but the thought of another full dinner made both of them duck quickly beneath their quilts in the hotel beds.

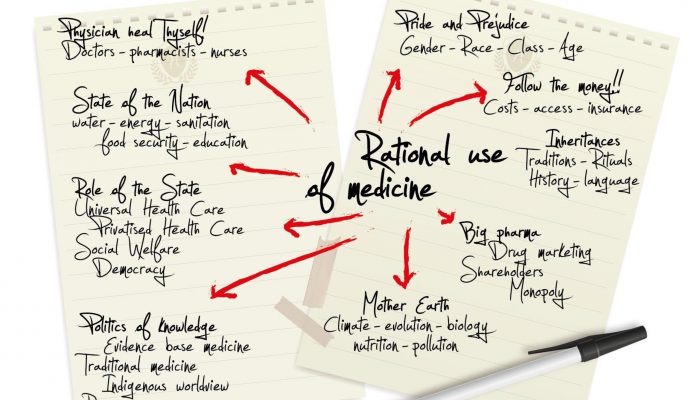

Sholmes however tossed and turned constantly and could not sleep easily as the different themes mentioned during the presentations kept buzzing in his head. The day’s proceedings had been wide-ranging and it was clear that, besides the various suspects involved, there were many systemic factors driving inappropriate use of medicine. Sholmes had to put all this information down somewhere just to get it out of his mind. Sholmes pulled out a sheet from a notebook provided by the hotel and began drawing another mind map. (featured image)

The drawing done, Sholmes quickly fell asleep, dreaming of fish ‘n chips and all kinds of home food that felt very safe and comforting as far as his digestive system was concerned!