UNIVERSAL HEALTH CARE AS THE ONLY ALTERNATIV

Rationally speaking, this pandemic has given us a great opportunity to have an insight to such a flawed system and put it into a right perspective so as to implement Universal Health Care (UHC). UHC, in broad terms refers to a health care system where all people receive quality and comprehensive health care preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative, at free of cost without discrimination and reference to their paying capacity. At present, all developed nations (except US) have UHC. On the other hand, almost no developing countries provide UHC. Notable exceptions include China, Sri Lanka, Peru, Thailand, and Cuba.

UHC is not a new concept in India either. The Bhore committee (1946) had recommended that India should have a health system that ‘‘is designed to provide [a full range of health care] for everyone who wishes to use it…. everyone who uses the new service is assured of ready access to whichever of its branches he or she needs’. ‘Nobody should be denied access to health services for his inability to pay’. This report was accepted by the Government after independence and primary health care centres to provide integrated primitive, preventive curative and rehabilitated services to the entire rural population free of cost as an integral component of wider community Development Programme. It also sought to integrate health services approach as a component of intersect oral action to take care of social determinants. This was also the vision articulated by Alma Ata Declaration on Primary Health Care of WHO in 1978. The involvement of community in Health Planning Identification of their needs and priorities as well as implementation and management of health and other related programmes was again emphasized in NHP 1982.

But over a period of time from National Health Policy Document (1982) to NHP (2015) this vision of UHC has been diluted variously to limit it to ‘essential’, ‘elementary’ primary’ health care so as to restrict the range of health services to be provided to cover only immunization, emergency care and top down, cost ineffective, vertical disease central programmes. There was over-reliance on the use of technology; no effort was made to understand community needs and to involve community in Health Planning and Management. This was in tune with the global development policy that was dominated by neo-liberal macroeconomics with its emphasis on cuts in public spending and reduction of fiscal deficits, since the 1980s. The Government’s flagship programme National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), launched in 2005, did include strengthening public health services, but there was neither restoration of Bhore Committees’ vision of healthcare any mention of universal provision of health services.

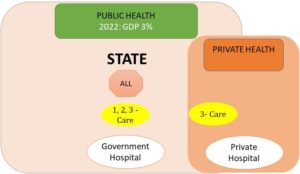

It was only in 2010, when the Government of India commissioned High Level Expert Group (HLEG) under Dr. K. Srinath Reddy that UHC once again entered the lexicon of health policy makers. The HLEG report recommended that India should achieve UHC by 2022 by increasing government public expenditures on health from 1.4% of GDP to at least 2.5% by 2017, and to at least 3% of GDP by 2022. This was to support free of cost primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare delivery through strengthened public health services. When required, Government would purchase private services (through agencies) i.e. without involving third-party insurance as it leads to higher health costs and lower levels of wellness at the population level. Availability of free essential medicines would be ensured by increasing public spending on drug procurement. These facilities will be provided cashless to all citizens of India through a pan India Health card. General taxation will be the principal source of health care financing, complemented by additional mandatory deductions from salaried individuals & tax payers. The 12th five-year plan was tabled soon thereafter by the Manmohan Singh government, which as expected shamelessly defaulted on the recommendations. On the contrary to what was expected, the government decided to give up all its responsibilities to private health services and health insurance. It was to act from side lines as a manager. The idea was to promote corporate hospitals by giving tax concessions and subsidies, so they can continue providing profitable tertiary care services. In short, government decided to continue with the failed ‘Out of Pocket’ health policy of US and Mexico.

Figure 5: HLEG 2011 Recommendations which suggested that State should increase public health expenses to 3% by 2022 and provide primary, secondary, and tertiary treatment free of cost. State can also purchase some tertiary care from private resources directly when required, without involving third-party insurance

Modi came to power in 2014 promising UHC to all citizens of India in his pre-poll campaign. But with time, the UHC promises have quietly been replaced with assurances. Somewhere in between he even managed to bring in a new National Health Policy 2017, and even proposed a health budget of 2.5% of GDP. This remained on papers, as the health budget has gone down quietly from 1.04% to <1% of GDP in the last 3 years. Meanwhile, the government went on to repackage the existing insurance-based schemes as ‘Ayushman Bharat’. This diverted the already scarce funds into private sector further as the NITI Ayaog went public with strong reservation against any increase in public health sector investment, including free drugs or diagnostics. The proposed plan to privatize the district hospitals (with at least 750 beds) under the illusion of public-private partnership is set to finish-off the remaining primary and secondary public health care system. Such two set of contrasting policies seems to a ploy to create confusion and nothing else.

Compared to, Thailand began implementing UHC only in 2002. Backed by enormous political will, pressure from people and civil society groups, it had covered 98% of the population in a decade. It’s completely financed by the government, through general tax, and covers nearly 80% of the healthcare needs of people compared to India’s 30%. The risk of health catastrophes has since then dramatically fallen and people feel safe and secure. The per capita expenditure on health in Thailand is nearly four times than that of India, but it spends only 4.1% of GDP (compared to India’s 3.9%). The crucial difference lies in the fact that 80% of this 4.1% is government spending (and not private). This optimizes the cost as the government purchases ‘quality’ services from ‘state of the art’ private hospitals at a very low price. Such robust public healthcare system has in fact helped Thailand to become one of the most successful country in combatting the corona virus with almost new cases and deaths since mid-May.

To sum-up, “Healthcare is a human right and not a luxury”.

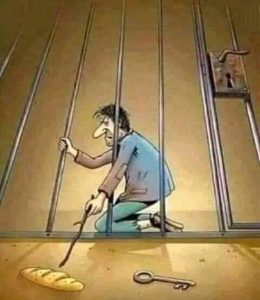

Failure of State in ensuring UHC is not a question of feasibility anymore, but lack of political will and priority which keeps the interest of corporate and insurance sector before that of the common man, whose ignorance is exploited with false assurances. Current Corona pandemic has thus provided us with a golden opportunity to unite such people belonging to all facets of life in understanding these false pretences and help us realize that without UHC, ‘quality’ healthcare delivery will remain inaccessible to the majority for sure.