Unlike huge building signifying excellence of academics, the CMC started rather unassumingly. Percival Spear explains the difference in an amusing manner – “The West loves a sign, and when it finds no large buildings labelled “the Smith College” or “the Jones High School” it is apt to assume that there is no such thing as education in the land. Herein lies one of the most fruitful sources of misunderstanding of things Indian.”[1]

Further, “those who complain that India has no material genius find nothing because they are looking for complexity when they should be looking for simplicity.”[2] In the parliamentary battle of 1813 the free-traders had stripped the East India Company of its commercial monopoly over India. “Free trade was its solid foundation. Evangelicalism had provided its programme of social reform, its force of character, and its missionary zeal.”[3]

Eric Stokes reminds – “It was in that year (1818) that the orator of the new liberalism, the young Macaulay, shook off his father’s toryism and avowed himself a Radical. It was in the same year that James Mill published his great History of India, and became a candidate for high office in the Company’s Home Government.”[4] All these phenomena taken together led to a condition where Macaulay was backed by the great bulk of Calcutta mercantile community in its fight for English education. It was the period gestating the formation of semi-modern Indian state. In tandem, changes occurred in education policy – a constituent part of which was medical education. Medical education historically became one of the most productive imperialist networks through which benefits of imperialism could be visible. In England, there were circumstances in which social resentment and political radicalism could flourish; during the 1830s and 1840s a British revolution seemed a real possibility.

The making of a new medical pedagogy as well as the emergence of a new gentry of students, getting extricated themselves from ubiquitous presence of theology, grew out of long-drawn socio-economic and political struggle in England and Europe. But, unlike UCL, abandonment of religious teachings in the CMC had nothing to do with historical developments as happened in Europe. In India in the 1830s it was actually a truncated representation of secularism emanating from colonial anxieties – not to interfere with religious beliefs of colonial subjects. The colonial authority almost always maintained a policy of equidistance and religious neutrality. The first cadaveric dissection seems to transform colonial medical anxiety to secular self-confidence.

The premises previously occupied by the Petty-Court Jail, an Arrangement old house situated in the rear of the Hindu College, were converted for starting to the use of the newly started Medical College. The books and the apparatus of the abolished Native Medical Institution were made over. Along with, Pandit Madhusudhan Gupta, who was a Baidya Professor at the Sanskrit College, was transferred, with two assistants, from the College.

It is noteworthy that the founding band of workers (professors) commenced their labours of teaching at the the CMC on the 20th February 1835. There were neither Library, Museum, Hospital nor “Philosophical” apparatus. Anatomical preparations were however soon procured from England (including two skeletons which were purchased through Messrs. Bathgate and Co. of Calcutta at a cost of Rs. 1,500) and the services of one Mr. Evans were secured as Curator to the newly established museum. Besides these difficulties, the teachers were confronted with the task of combating a strong national prejudice against the study of anatomy or dissection. This prejudice was so deep-rooted among the greater part of the community, that their contemporaries laughed at the attempt to introduce it, with scorn “as a vain chimera.”

Though the best of their friends assisted them with a remarkable and modified degree of encouragement, uncertain of the propriety of committing themselves to approve of what appeared at the best a very, doubtful experiment. To overcome this, parts of the human body were first introduced in illustration at the daily instruction, and these gradually replaced the sheep’s brain, goat’s livers, wooden models and tin representations, which formerly served the purpose of teaching anatomy. It took six months to institute the required course of anatomical lectures, and when Dr. H. H. Goodeve first placed an entire dead human body on the lecture table, it created much interest, and some excitement among the pupils, who however, very soon became familiar with the sight from daily repetition.[5]

Almost after the foundation of the CMC, Bentinck returned to UK. In 1836 Lord Auckland was appointed as the Governor-General of India. His private secretary was John Russell Colvin. He ruled India from 1836 to 1842. Hence the growth and development of the CMC took place during his tenure. To write a history of the CMC we shall have to take into account both primary and secondary sources. For example, the first annual report (though incomplete to an extent owing to Bramley’s premature death and, moreover, he could not present it himself for the same reason) or various reports in the GCPI or GRPI do belong to primary sources. On the other hand, someone else’s personal account or any later accounts should be regarded as secondary sources. For my purpose, I shall try to consistently use heavily the primary sources.

To mention, when Bramley prepared the first annual progress report of the institution his assistants Goodeve and W. B. O’Shaughnessy must have seen it before its submission. Hence it is expected that any discrepancy in the report should probably have been rectified. However, first annual report of the CMC started thus, “The following Report was drawn up by the late Principal shortly before his death, and was afterwards found among his papers. It breaks off abruptly, but the chief matters requiring notice are fully detailed in it.”[6] Moreover, it was stated, “We lament the loss of which the cause of native improvement has suffered from the death of Principal Bramley; and this regret has been enhanced by the perusal of the following Report, which, besides describing in a very interesting manner the successive steps by which the Medical College has been brought to its present state of efficiency”.[7] Finally, “few measures which have been adopted by the British Government in this country will reflect more lasting honor on that Government than the foundation of the Medical College.”[8]

Almost at the beginning of his report Bramley stated, “The Institution of the present Medical College has been attended, at all its stages, with difficulties of no common order. At the very period of its foundation, a discussion between the advocates of different systems of Anglo-Oriental education was carried on with much vehemence by either party, and it appeared that to ensure the success of the educational system on behalf of which I was interested it would be incumbent upon me to adopt such a line of conduct, as, without compromising me with this or that set of Opinionists, would enable me to carry through my own views with merely a nominal attachment to either.”[9]

Moreover, “I esteem myself not a little fortunate ¡n having succeeded in keeping aloof altogether, from even a connexion by name with the partisans of different declared systems of education, since the newly formed institution was hereby constituted neutral ground upon which all might meet, by which all might benefit, and on which none need be compromised.”[10] To be sure, it was colonial modernity, where “useful knowledge” and “capable practitioners” instead of “capable enquirers and practitioners” were prioritized. The avowed secular social hierarchy disseminating through English education and governance in general and medical education in particular was irrupted by frequent use of phrases like “Hindu medicine” or “Hindu medical students”. Caste and religion seem to insinuate the half-grown project of modernity in India. But, keeping debates away for the time, from these statements it somewhat strongly transpires that the new Medical College had led to the emergence of a secular social hierarchy where old rules and customs of getting higher status in society was replaced by merit, education and efficiency. A new Calcutta began to germinate within the womb of the old traditional Calcutta.

How Bramley and other high British officials did select the prospective students of the CMC? Bramley writes, “In pursuance of the Regulations of the College, as defined in the Government Order of January 28, 1835 (Govt. G.O. No. 28 of 28th Jan., 1835) a preliminary examination was held on the 1st May, at the residence of J. C. C. Sutherland, Esq. Secretary to the Committee of Public Instruction, for the purpose of selecting the students on the foundation.”[11] Further, “On this occasion about a hundred candidates presented themselves; the majority being Hindu youths of various denominations. The greater part of these lads had received their education at Mr. Hare’s school, the Hindu College, and the Scotch Assembly School the remainder had been instructed at the minor academical Institutions in the city. The examination was conducted chiefly by Mr. Sutherland, and the acquirements of the candidates were severally tested in the elementary branches of English knowledge, in Arithmetic, and in Bengalee … twenty-five were selected as stipendiary students.”[12]

As most the students were already taught in Mr. Hare’s school, the Hindu College or the Scotch Assembly, they had acquired some kind of European habits like clock-time acculturation and punctuality. It can be assumed that the selection procedure was quite rigorous to admit 25% of aspiring candidates. Then a “second trial on some future occasion” was deemed and promised.[13] Moreover, “all of them had passed through and understood the Arithmetical gradations as far as fractions and decimals. In Bengalee their acquirements (as remarked by Mr. Sutherland and the Pundit Moodusoodan) were, with two or three exceptions, slender’ and to improve their knowledge and acquirements “an arrangement was entered into between Mr. Hare and myself, by which the pupils were enabled for a few months longer to continue their attendance at their school classes without interfering with their medical studies. This combination of general with special instruction had its advantages. It not only increased their positive knowledge, but it enabled me to ascertain whether their having embraced the study of medicine”[14].

The report (GCPI) says, “Dr. Bramley rendered another important service to the cause of medical science in India by preparing a medical dictionary for the use of native students. A book of reference of this kind was essential for the aid of learners, whether at their homes or at college”[15]. Moreover, it was stated, “The new organisation which was given to the college on the death of Dr. Bramley is detailed in the letter which was addressed to us by the orders of your Lordship in Council on the 15th February last, which, with a view to render this sketch as complete as possible, we will insert in this place.”[16] Now the question arises – how the classes at the CMC could be started on 20 February (as is conventionally accepted), 1835 if the selection process was held on 1 May, 1835? Plausible answer to this riddle is that the selection process took place after the starting of the classes on the date above-mentioned.

Besides Goodeve and W. B. O’Shaughnessy, government appointed “Dr. C. C. Egerton to be professor of surgery and clinical surgery, on a salary of 400 Rs. out of the funds of the college in addition to that assigned to him for superintending the Ophthalmic institution.” Also, “Dr. T. Chapman recently appointed Assistant Surgeon in the General Hospital will give lectures on clinical medicine, drawing a salary of 200 Rs. per mouth from the college.” And “The Governor General in Council has further appointed Dr. Wallich lecturer on Botany in the Medical College, and he will receive from the funds of the college an allowance of 50 Rs. per mensem to cover the expense of a boat. Mr. R. O’Shaughnessy has been appointed demonstrator to the dissecting room (an officer understood to be much wanted in the college) and to give assistance to the chemical lecturer, on a salary of 150 Rs. per mensem”. And, finally, “Mr. D. Hare has been nominated Secretary of the Medical College with a salary of 400 Rs. to cover (with the aid of such establishment of clerks, &c. as was allowed to Dr. Bramley) all charges of accounts and correspondence, and the general business of the college.”[17]

“The College Council has, as your Lordship in Council is aware, proposed that the projected Fever Hospital should be united with the Medical College, by which means a highly efficient amount of medical attendance would be ensured to the patients, at the same time that every requisite facility would be afforded for the instruction of the students.” Moreover, “A museum and library have been attached to the College, the present contents of which will be seen from the Appendix No. 9. Contributions to either by individuals or public bodies in any part of the world, who wish to aid the progress of European medical science in India, would facilitate the studies of the pupils, and afford them encouraging proofs that this great experiment is regarded with general interest.”[18]

It can be understood that in the early years of its foundation the CMC was regarded as a “great experiment”, not an entirely finished task, for “the progress of European medical science in India”[19]. Again, the way the students were selected initially may be viewed as a proto-entrance examination of today’s India.

However, it is noteworthy, at the beginning “[t]here were neither Library, Museum, Hospital nor “Philosophical” apparatus. Anatomical preparations were however soon procured from England (including two skeletons which were purchased through Messrs. Bathgate and Co. of Calcutta at a cost of Rs. 1,500) and the services of one Mr. Evans were secured as Curator to the newly established museum. Besides these difficulties, the teachers were confronted with the task of combating a strong national prejudice against the study of Anatomy or dissection.”[20] Regarding the success of this “experimental” institution in India there was also strong sense of disbelief and doubt among the British too. It is understood from the inaugural address of Mr. Bethune at 1849-1850 academic sessions.

Bethune said, “The institution consisted of an old house in the rear of the Hindu College, in which two young Assistant Surgeons, to whom a third was subsequently, and after much difficulty, added, were expected to teach the whole circle of medical science to a class of upwards of fifty students. There was neither library, museum, hospital, nor philosophical apparatus; and we had to combat national prejudices against the study of anatomy, which were considered so deeply rooted, that the greater part of the community laughed (at) the attempt to scorn as a vain chimera…[21]”.

However, according to Bramley’s report “shortly after the opening of the college on the 1st of June, forty-nine stipendiary students had been enlisted.”[22] Bramley’s report extends from pages 31 to 67 of the GCPI and he noted, “My intention being to render these, the first pupils, not only proficient in the usual routine of Medical Science, but also capable of exercising their minds freely upon general subjects, in order to ensure the application, and not the simple acquirement of knowledge, I was much struck with the unwholesome and unsettled state into which their minds had been thrown, and with the imperfect condition of their physical powers, owing partly to the nature of their early education, as to what had been done, but perhaps more as to what had been neglected.” [23]

He also found “the natural precocity of the minds of these native youths, fostered and forced into unnatural action, by being employed on speculative subjects before they had been taught or understood the nature of practical ones. The general taste of all these boys took, I found, in this respect the same bent and inclination”[24] To Bramley, it was an impediment to the furtherance of European medical education in India. Further, “as a consequence, they had learnt to cherish a false estimate of learning, in so far that the test of acquirement was held among them to be, the extent of abstract rather than positive knowledge possessed by the recipient, or in other words, that learning was with them of higher value than wisdom.”[25] He realized, “It is true, that knowledge is power; but it furnishes the power to do evil as well as good: it follows, that misdirected and unassisted knowledge is mischievous in proportion to its extent.”[26]

Bramley also made a significant observation while comparing England and India with regard to higher education, “In England, where education mingles a domestic with a school life, combining the advantage which is to be derived from the learning of a master, the emulation which results from the society of other boys, and the affectionate vigilance of parents, the heart and head are educated at one and the same time. But in this country, and at the present time, there exists no indirect controlling power whatever, no natural example which the pupil is either enabled, or is content to follow. For the Master’s authority is confined to the School-room; and a European education leads the youth to despise the knowledge of his parent, and disdain his control, the great majority of youths in his position becoming necessarily elevated above their guardians in the scale of knowledge and in the rank they hold in Society.” [27]

As he found, the same moral and physical cause still operating to the prejudice of his naturally enfeebled frame, he also found that medicine merely palliates but does not cure him, so that by the time he reaches what ought to have been the prime of life, he is a confirmed hypochondriac, and in the end. the body either wastes, consigning him to an early grave, or he becomes plethoric and bloated, so as to render life a burden rather than a blessing, “Living to eat, rather than eating to live.”[28] With this orientation he began his for moral as well as physical training of the students. It transpires that a new kind of physical and moral acculturations consistent with European mode of thinking and living began to operate.

More elaborately he explained it, “The above exposition of my policy with regard to the internal management of the Medical College, will account for the absence of any fixed academical regulations, other than of the simplest and most obvious nature. I have considered the whole of the attempt as purely experimental, and I have been guided throughout by the course of circumstances, intending rather to suit my arrangements to the peculiarities of my position, than increase my difficulties in the first instance, by establishing at the outset, regulations, devised in utter inexperience of the character and habits of those to whom they were meant to apply, or of the institution to which it was intended to adapt them.” [29]

We should remember that Bramley’s feat until his premature death (19 January, 1837) to indoctrinate his students into “strict code of moral, intellectual and habitual discipline” smoothed the way for future teachers and disciplined and docile modern citizenry. He wrote, “to educate natives so as to combine the communication of knowledge with the regulations of their minds and the directions of their habits of thought.”[30] Moreover, “I have endeavoured to prove to them that I am not only their instructor but their anxious friend, ready to advise and assist them, and desirous not less of their moral improvement and their general welfare, than to see them succeed, under the instructions of my colleagues and myself, in the honorable profession they have made choice of.”[31]

Having performed these basic tasks and reconstituting the students’ general and unique Indian psychological, bodily and habitual components, real medical education started its classroom journey and pedagogy at the CMC. They were, according to Bramley’s report, arranged in the following manners.

General Instruction

Bramley explicitly wrote down his plan, possibly in consultation with Goodeve and O’Shaughnessy. “On this point I propose to consider the nature and extent of the education already given, the means of instruction, and the general plan of teaching. Hitherto the instruction conveyed to the pupils comprehends Lectures upon General and Practical Anatomy, Physiology, General and Practical Chemistry, Theory and Practice of Physic, Elements of Medical Botany and Materia Medica, Practical Pharmacy, together with hospital attendance.”[32]

Then he discussed in details about anatomy teaching and classes. Anatomy teaching and classes were conducted by Bramley himself and Goodeve. Regarding anatomy teaching he made an interesting remark, “establishing a systematic mode of teaching, and as far as means and circumstances would permit to frame the general Instruction of the College on the mode of the English Medical Schools.”[33] From his observation it transpires that universal or European medical science had undergone some amount of refraction and mutation to make it compatible with the “local” or specificity of Indian circumstances. These specificities were seen thus. In the first place, “It was important therefore, that their capabilities should be tested as soon as possible as to their power to receive instruction in a science, the very elements of which are crowded with technicalities, for whose etymology the English language forms no guide.”[34] Again, In the second place it was essential to the well working of the general plan to ascertain, at as early a period as possible, the tastes and dispositions of the pupils, to receive instruction in a science to them perfectly novel, and under any circumstances by no means inviting at the outset, and the first approach to which must necessarily be made amidst the gloom of prejudice, and the confusion of ignorance.”[35]

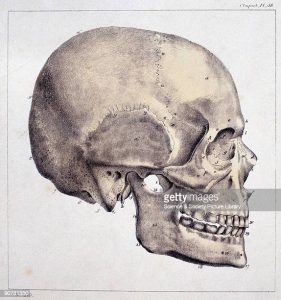

As a sequel to these issues, “Thirdly, it was expedient that the first step should be made in that branch of science which was destined to hold the capital place in the studies of the College, and also to experimentalize on the willingness of the students to be taught the first rudiments of their art by the actual demonstration of human bones.”[36] It enabled Bramley to see how far their prejudices might be infringed on without hazard; while the selection of osteology to commence with imposed a somewhat severe tax on their patience and industry, as the subject is difficult, and at the same time dry and uninteresting. In this way the large arteries, the principal muscles and nerves, &c. which during lecture were spoken of as connected with any particular bone were explained and demonstrated on the ensuing day. “During the osteological lectures the subject was taught entirely upon human bones, which after lecture were placed in the pupil’s hands for their individual observation and examination, and were closely studied by them.”[37]

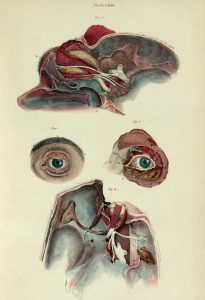

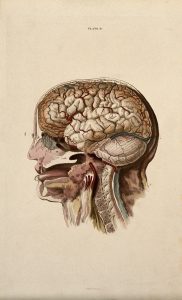

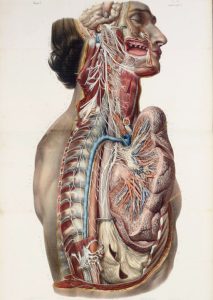

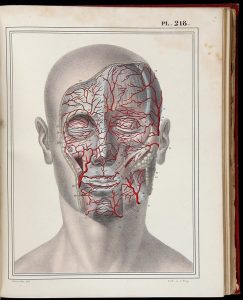

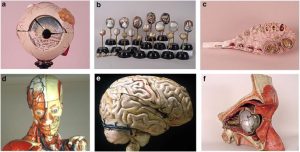

Not the slightest repugnance was shewn at any time in this proceeding; indeed the youths appeared rather to exult in overcoming their national prejudices in these matters. The auxiliary demonstrations were made upon the valuable plates in Cloquet’s celebrated work presented to the College by Dr. Duncan Stew art; by Lizar’s plates; those of Tusón and the Papier Maché models of the human frame which the College possesses. In this manner the students, as far as such means would enable them, acquired a practical knowledge of the subject before them, and during these three months made such progress as to leave no doubt on the most sceptical mind of their power to comprehend what they had been taught.[38]

It should mentioned here that as a medical student in Paris, Louis Thomas Jérôme Auzoux (1797-1880) noticed that there was often a shortage of human remains available for doing human dissections. Dissections were an essential part of studying medicine. However, even if a body was available, it could only be used once before it began to decompose.

To deal with the shortage of bodies, Auzoux began producing accurate anatomical models that could be taken apart piece by piece. The models were sturdy and inexpensive, especially when made with the secret papier-mâché mixture that Auzoux had developed. The mixture contained cork and clay as well as paper and glue. Introducing papier-mâché as a modelling material was a radical change from earlier modelling techniques. In previous centuries, anatomists and artists made their anatomical models using wax.

For sure, it was another step ahead towards visual, verbal and psychic acculturations. Some of the plates shown to the students are represented below.

(Cloquet’s plate of skull)

(Lizars’ plate of brain and interior of the eyes)

(Tuson’s Plate – from Guillotined body)

(Cloquet’s front of face)

(Various Papier Maché models of the human frame then in possession of the CMC)

Such classes on osteology and acquaintance with the 3rd dimension or the interiors of the body (which was hitherto unknown and non-existent in traditional knowledge systems like Ayurveda, Unani or Siddha) through various plates continued from 1 June, 1835 to 30 June, 1835, consisting of three lectures a week.[39] “The intermediate days were occupied by those ‘subjects which were touched upon in the lecture of the previous day, but which did not admit of more than cursory notice at the time , and could not be shewn to the pupils without interrupting the proper course of the subject under discussion.”[40] The college was closed on 1 October, 1835 and reopened its classes 31 March, 1836.[41] After reopening of the class students were able to explain all alien Greek or Latin terms used in anatomy.

“The beneficial results of this plan of teaching are constantly rendered apparent during the periodical examinations, where the custom is now established of calling upon any of the pupils to demonstrate a bone, and requiring him to explain and point out its relative position, its connections, its various processes and foramina, with the parts attached to or passing through them, and their ultimate distribution. These are described with surprising accuracy by the more studious and intelligent students, who will moreover prove their knowledge of the subject by answering almost any question which may be put, out of the immediate train of the examination.”[42]

Despite these facts Bramley laments, “we had not, and have not up to the present time, a single class-book in the Institution, and I believe it to be almost impossible to acquire by rote, that which is taught only by Lectures orally delivered in connection with objects under demonstration.”[43] So what they had to do all were from scratches. Truly inquisitive, original and scientific-minded scientist-doctors like O’Shaughnessy and Goodeve precisely dwelt on their efforts, “as teachers in a new and experimental institution”. They worked hard to structure the best curricula for CMC students form materials “drawn from attentive examination of all the British and foreign professional journals”.[44] They tried sincerely to bring the level of medical education imparted at the CMC at par with European medical schools. They jointly stated their desire in a plain way for the recognition of their endeavour in homeland – “It must not be said of us in Europe, that expatriation has not rendered us inefficient in the advancement of our profession. We will rather strive to excite among our brethren of the fatherland some surprise, that amidst the many impediments which beset us here, we will pursue with unabated zeal the various useful and enobling branches of our truly philanthropic art.”[45]

Unhesitatingly, Gorman comments, “As late as 1870 Charles Eliot, president of Harvard, declared “The ignorance and general incompetency of the average graduate of American Medical Schools … is something horrible to contemplate. In contrast to this situation, the Calcutta Medical College must be regarded as equal and possibly superior to the best and oldest schools on the Atlantic coast.”[46] Gorman pays his tribute to these founding stalwarts of the CMC, “Henry Goodeve and William O’Shaughnessy proclaimed that as teachers in a new project they built their courses of study from the contents of British and foreign journals. Of the seventeen medical journals they used, nine were French and eight British. They were very conscious of the challenge before them … Indeed, in one respect the curriculum at Calcutta was superior, for the emphasis the French placed on clinical subjects was accompanied by a disdain of the basic sciences. The Calcutta plan was more balanced.”[47]

Coming back to Bramley’s report, Bramley reported, “muscles, and arteries, nerves, viscera of the thorax and abdomen, Brain and organs of sense were considered. A considerable portion of physiology was likewise included in the lectures … Bones, plates and models, again formed the chief materials for illustrating the course, but occasionally portions of animals lately dead, and in a few instances, parts of fresh viscera of the human subject were introduced for demonstration.” Bramley was fully satisfied with the advancement the students made – “The technicalities of anatomical science chiefly derived from the Latin and Greek had been acquired with singular accuracy, and could be used and repeated by almost all the pupils with fluency and correctness.”[48] For example, “on the meaning of such a term as sterno-cleido-mastoideus, there was scarcely one who could not readily explain that it signified a muscle whose origin and insertion was denoted by the name”.[49] To attain a broader and more accurate knowledge of what the students learned “the custom is now established of calling upon any of the pupils to demonstrate a bone, and requiring him to explain and point out the relative position, its connections, its various processes and foramina … and their ultimate distribution.”[50]

The summer session from April to September was occupied by lectures on chemistry and the practice of physic, and “the second regular anatomical course did not commence till October 1836.”[51]

The introductory Lecture to this course, delivered by myself, was made as public as possible, and was honoured by the presence of the Right Honorable the Governor General and a large body of distinguished persons both native and European, whose visits on this, as upon all occasions, are of material service to the College, in marking to the pupils, and the native community the interest which the Government and the European public take in the prosperity of the College, and the importance they attach to it as a national Institution. Up to this period actual dissection which was destined to be the chief feature of this course, had not been practised by the class. If it had been desirable, no conveniences were in readiness for the purpose during the previous cold season, which is the only time such operations can be practised in this country.[52]

Another practical impediment was “under any circumstances, it would not have been advisable to put the dissecting knife into the hands of the students until they had acquired some familiarity with the nature and situation of the parts they were about to examine, nor until their moral training had been so ripened as to admit of the final, yet all important experiment being essayed, without risking the interests of the Institution.”[53] It was necessary to proceed with considerable caution, to take care that they were not too abruptly introduced to this new department of study, and that when entered upon, each step of the proceeding should be conducted under the most favorable circumstances.

Moreover, Bramley reminded, “Dissection is seldom approached by the uninitiated even in Europe, without feelings of aversion, and it was much to be dreaded lest the first impressions upon these youths, who were peculiarly sensitive to every feeling of the kind, should operate to alarm or discourage them from the pursuit which constituted the vital part of the desired innovation. It was moreover necessary to conduct the dissections with due regard to secrecy, as the students were naturally enough exceedingly averse to being exposed to the gaze of intruders, particularly as such exposure might entail the penalty of excommunication to themselves and their families, and prove most disastrous to the welfare of the cause in which they had embarked.” [54]

Despite these hindrances, Bramley informs us, “For the most part also the students looked with contempt upon the ignorant prejudices of their countrymen, and it was most delightful to witness the spirit current amongst them, to raise themselves above the evils of their condition.”[55] Hence “A rigid observance of these precautions, however, was all that was necessary to ensure success, for I had previously received unquestionable proofs of their intention to use the dissecting knife whenever called on to do so”. Finally, on 28 October, 1836 all doubt was removed. “On that day, which may be regarded as an eventful era in the annals of the Medical College, four of the most intelligent and respectable pupils, at their own solicitation undertook the dissection of the human subject, and in the presence of all the Professors of the College and of fourteen of their brother pupils, demonstrated they were hereafter to receive when the hospitals should be thrown open to their observation”.[56]

Bramley sincerely wanted to reward those brave boys “for the industry and moral courage of the students who have thus more especially distinguished themselves”. Finally, failing to reward these students, his despair became evident, “were their names brought to the notice of Government in the present report; but the same reason which induces them to conceal their anatomical labours, and the probable publicity of this document, forbids my making the disclosure.”[57]

It is interesting to note that prior to the historical act of dissection there was a great deal of anxiety among the concerned non-medical section of the English society.[58] For example, we can cite a long quote of Pearry Chand Mitra, “I will state however one fact which will shew how Mr. Hare was anxious to see the project of the Medical College finally brought about and settled without opposition. One evening as I was sitting with him, I saw Baboo Muddosuden Goopta the tlien professor of the Sanscrit Medical Science ot the Sanscrit College entering the room in all haste.

Mr. Hare viewing him said at once well—Muddoo what have you been doing all this time? Do vou not know what amount of pain and anxious thoughts you have kept me in for a week almost ? I have been to Radhacant, and I am hopeful from what he said to me. Now’ what, you have to say. Have you found the text in your shaster authorising the dissection of dead bodies”? Muddo answering in the affirmative said “Sir! fear no opposition from the orthodox section of the community, I and my Pundit friends arc prepared to nwet them it (hey come forward which I am sure they will not do”. Mr. I hire felt himself relieved at this declaration on the part of the Professor…”[59]

In 1833 Lord William Bentinck, not less attracted by the controversy than compelled by the deplorable state of medical education, appointed a committee to report on the whole subject. The members were: Surgeon J. Grant, the Apothecary General; Assistant-surgeons Bramley and Spens, Baboo Ram Komul Sen, T. C. C. Sutherland, the secretary to the Committee of Public Instruction, and Sir C. Trevclyan. For twelve months did these authorities, professional and educational, take evidence and deliberate, having submitted to the combatants on both sides from forty to fifty detailed questions. Being an influential person, educationist and philanthropist, Alexander Duff was strong advocate of dissection and the furtherance of European medical education at the CMC. He too was very anxious about repercussions of the Indian society of Calcutta and its surrounding. Led by Duff, Grant asked a barrage of questions to the students who all happened to be of Brahmin class. He began: “You have got many sacred looks, have you not?” “Oh yes,” was the reply,” we have many Shasters believed to be of divine authority. Some are very old, and others have been written by Rishis (holy sages) inspired by the gods. They are upon all subjects, literature, science such as it is, chronology, geography and genealogies of the gods.” “Have you not also medical Shasters, which profess to teach everything connected with the healing art?” “Oh yes,” they said,” but these are in the keeping of the Bhoido or physician caste; none of us belong to that caste, so that we do not know much about them.” “Do your doctors learn or practise what we call anatomy, or the examination of the human body with a view to ascertain its real structure in order skilfully to treat wounds, bruises, fractures, etc.?” “We have heard them say that anatomy is taught in the Shasters, but it cannot be like your anatomy.” “Why not?” “Because respectable Hindoos are forbidden by imperative rules of caste to touch a dead body for any purpose whatever; so that from examination of the dead body our doctors can learn nothing about the real structure of the human body.” “Whence then have they got the anatomy which, you say, is taught in the Shasters?” “They have got it out of their own brains, though the belief is that this strange Shaster anatomy must be true or correct, it being revealed by the god; but we now look upon this as nonsense.”[60]

However, Bramley was very much emphatic about his students’ achievements, though owing to social prejudices and inhibition prevailing in the society, beyond the college campus, forbade him to disclose their names – “since this time dissections have been regularly practised by all the senior class with one solitary exception; and in point of knowledge derivable from this source, the majority of the students may be considered on a par with the pupils of the English schools of medicine, possessing the same, if not more abundant, opportunities for its acquisition, equal intelligence, zeal, and industry.”[61] Again, as a sequel to previous taboos, “the same reason which induces them to conceal their anatomical labours, and the probable publicity of this document, forbids my making the disclosure.”[62] As feared by Bramley, there was huge uproar in Bengali society – “The first demonstration by dissection caused great anxiety. The College gates were closed to prevent forcible interruption of that awful act”.[63] From another account we come to know “I have heard from people of that time that this human dissection aroused a tumultuous social situation and great stir among people … the leadership of the Nabya-Banga (New Bengal) encouraged those students who did dissection and thus began to invigorate the new college.”[64] Against this perspective, it seems improbable and is hard to swallow the fact as stated by Arnold that “The momentous event was duly celebrated, in rather militaristic fashion, by firing a fifty-round salute from the guns of Calcutta’s Fort William.”[65]

According to Bramley, four of the most brilliant students, whose names were not disclosed for the fear of social repugnance, did the first dissection on 28 October 1836. These four students, as narrated by Dr. Mahendrala Sircar (the second M.D. from the Calcutta University), were Umacharan Set, Rajkrishna De, Dwarakanath Gupta and Nabin Chandra Mitra comprised the first batch of students to take part in dissection. Sircar wrote in 1873, “It would have been impossible at this distance of time to find the names of the “four intelligent and respectable pupils” of Mr. Bramley … These are no other than Babu Uma Charan Sett, who has just retired from an honourable service of thirty-four years, and Babu Dwarakanath Gupta, who has been practising as a private practitioner, ever since he graduated.” [66]Amongst them, Rajkrishna (Raj Kisto) Dey “is stated to be the first Hindu student who dissected the human body … They, however, all agree in stating that Babu Raj Kisto Dey was the individual who was the first to plunge the scalpel into the dead human body, and to whom therefore the need of being the pioneer of dissection is due. Pandit Madusudan, having been an assistant tutor, was, as a matter of course, present on the occasion, but he did not actually take part in the dissection.”[67]

Later on R. Havelock Charles (appointed as the Professor of Anatomy at the Medical College, Calcutta, and surgeon at the College Hospital in 1894) emphasized: “The most interesting feature is that in 1835 the Hindu prejudice against touching dead bodies first gave way, and much credit must be given to the original class of eleven students who had the courage to break through the iron bonds of caste, and engage in the dissection of the human body. I think it but right to mention the names of the students of this first class that studied human anatomy in India. They were: Umacharan Set, Dwarkanath Gnipto, Rajkisto Dey, Gobind Chunder Goopto, Kallachand Dey, Gopalchander Gupto, Chummuin Lal, Nobin Chunder Mitter, Nobin Chunder Mookerjee, Buddinchunder Chowdree, and James Pote. I do so for two reasons; first, to honour those who, throwing aside the trammels of prejudice, withstood firmly the strong moral pressure brought to bear on them by the outraged feelings of a kindred whose customs are the type of a crystallized conservatism; and, secondly, that although I835 is not so very long ago, these men have practically been forgotten…[68]

He further added, “Pandit Madusudden Gupta, who for good work as a demonstrator of anatomy had his portrait in oils presented to the Anatomical Department, where it hangs at present in the lecture-room. The Pandit passed his examination in 1840, and as I write, I have a copy of his diploma before me. The students whose names I have mentioned were examined and passed in 1838, yet the Pandit alone is remembered; his predecessors are Vixere fortes ante Agamemnona!”[69]

According to Bramley’s report, besides the pivotal job of dissection there were important classes on “Theory and Practice of Physic”. In these classes, “lectures were delivered by Professor Goodeve and occupied from May to September, 1836. The object of the professor in this course was to instil into the minds of the students the groundwork of the science, and prepare them for the reception of practical information which they were hereafter to receive when the hospitals should be thrown open to their observation, and when clinical instruction (which it was then too early to commence) should become available. The subject therefore was treated in a purely elementary manner, and directed to the theory and principles, rather than the practice of physic.”[70]

Despite these limitations of the time where theoretical classes prevailed over the practice of physic, “These lectures, however afforded the pupils an insight into pathology, explained to them the nature and cause of disease in general, laid down the objects to be pursued in removing it, or palliating it, without however, entering at length into the details of therapeutics. At the same time the instruction thus given, served to disabuse them of many prejudices and foolish ideas which they bad gathered from the deplorable ignorance of their countrymen upon all medical questions.”

Next was the course of “Hospital Attendance” which is briefly described. As Bramley’s report lets us know: “The summer session of 1836 being now closed, and the pupils having acquired a considerable degree of proficiency in Anatomy and the broad principles of medical and surgical science, I thought that the most fitting season had arrived to introduce them to studies of a purely practical nature, and accordingly arrangements were made for their attendance at the Native Hospital, the General Hospital, the Eye Infirmary, and the Kolingah Dispensary; the first of these from its convenient distance from the College, became the favorite place of resort, and I am happy to say that they availed themselves fully of the benefits which that excellent Institution affords. The greater part of the class were exceedingly regular in their attendance, observing closely the eases, noting carefully their symptoms, and treatment, and receiving with great attention the remarks made to them upon the diseases they witnessed. Most of them were anxious and ready to assist in the various minor operations, and some of them performed them with confidence and dexterity … at the same time they accustomed themselves to the disagreeable sights and impressions to be met with amongst the sick in hospital sights which even to an experienced practitioner are frequently painful in the extreme, and to the young student sometimes the source qf unconquerable repugnance. Their attendance at the Eye Infirmary, the General Hospital, and the Kolingah Dispensary, was less regular than at the Native Hospital owing to these institutions being situated at a much greater distance from the College than this.[71]

Keeping the plight of transportation of Calcutta during the period under discussion, students had to walk several miles to reach the General Hospital, Kolingah Dispensary or the Eye Infirmary. During the summer or rainy season it was almost a inhumane task. So the students could not attend these institutions regularly. But the Native Hospital was in the vicinity of the CMC. As a result, the students were regular attendees here.[72]

Then Bramley proceeds to describe the “Practical Pharmacy” classes. Since the opening of the new session 16 students were to attend the class three times a week. This class was formed so that it could suit “the peculiar circumstances of the native students” who were studying in a foreign language and who had no other means acquire knowledge of this particular branch of science without attending the General Hospital and other hospitals mentioned above. Their instruction was carried out in the following manner, “The class is made to stand before the Professor, and each student in his turn is called upon to read aloud on the subject selected for the day’s discourse. As he proceeds defects of The instruction in this branch is conveyed in the following manner. The class is made to stand before the Professor, and each student in his turn is called upon to read aloud on the subject selected for the days discourse. As he proceeds defects of pronunciation are corrected, he is required to explain any technical phraseology which may occur in the passages he reads, and he is closely questioned on the general meaning of the whole; observations are introduced by the instructor”[73].

Bramley goes further, “The subjects discussed comprehend the whole range of Therapeutics, hence opportunities are constantly afforded for enlarging the student’s knowledge on matters of the highest importance, such as those which bear reference to the moral as well as medical treatment of disease, and the general laws of Hygeine. These could not be so advantageously, or so familiarly treated of, in stated public lectures.”[74] It is interesting to note two points here – (1) a moral component was induced in the treatment of diseases, and (2) general laws of hygiene was being taught at the College from its very beginning. Though, to speak, hygiene as a separate branch of teaching was incorporated in the syllabus at a much later period. Bramley’s original intention was “to have delivered these during the present Session, but owing to the pupils time being so fully occupied in, the study of Practical Anatomy Materia Medica, Medicine and Pharmacy, I have, at the suggestion of my Colleagues, postponed the course till the summer session.”[75]

Next he elaborated on the classes of “Chemistry and Materia Medica” – “The course of instruction in Chemistry was commenced in this Institution in January 1836, as Dr. O’Shaughnessy was anxious if possible to test the aptitude and inclination of the pupils for a science of the nature of which they had no previous idea.”[76]

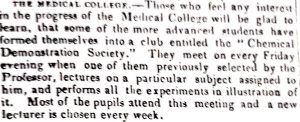

But in stark contrast to such anxious presumptions “several of the young men… evinced a strong desire to become experimentalists themselves, and were known to purchase at (to them) enormous expence (sic), various tests and articles of apparatus with which they repeated at their homes the experiment they witnessed in the lecture rooms” and “guided by these data Doctor O’Shaughnessy with my full concurrence decided on a plan of instruction calculated to enable the students to acquire the most minute information on every department of chemistry…”[77] Moreover, “twenty of the most distinguished pupils were instructed in the manipulation of apparatus, preparation of reagents, &c. being the repetition of the experiments performed in the Professor’s Lectures … and with the mode of preparation of many of the most useful mineral remedies”.[78] Importantly, “It is worthy of remark too that no servants were allowed to the class, the practical pupils themselves making the fires, cleaning the vessels employed, applying clay lutes, &c.”[79] It was jubilantly reported in a Calcutta journal that some of the more advanced students with great zeal went so far to form the first “Chemical Demonstration Society” of India.[80]

They would meet on every Friday evening when one of them previously selected by the Professor lectures on a subject assigned to him, and performs all the experiments in illustration of it. Most of the pupils attend this meeting and a new lecturer is chosen every week.

Strengthened by these developments, Bramley, with a happy, content and emphatic note, reported: “Dr. O’Shaughnessy is prepared to furnish an estimate and plan for the supply of all essential apparatus in the general as well as practical department. The expense will be found so small, especially when contrasted with the benefits to be derived from the supply, that I earnestly solicit the sanction of the Committee to the proposed expenditure. With respect to the course of instruction on material medica, also conducted by Dr. O’Shaughnessy, it has not yet proceeded to a sufficient length to call for any detailed notice. [81]

As we noted earlier, metropolitan/universal science underwent some amount of refraction in the colonies like India. It is quite well explained in Bramley’s report too, “no complete apparatus having been provided for the establishment, the Professor is himself compelled to devote a considerable portion of time to the actual manual labour of glass-blowing, &c. which he could otherwise employ in the instruction of the pupils. The illustrations of each lecture necessitate the taking to pieces and re-adjustment of the apparatus used the preceding day, thereby adding greatly to the labours of the teacher, and subtracting from the benefit he could otherwise confer on his class.[82]

Dr. O’Shaughnessy introduced his course by twelve Lectures on the elements of botany, in which the structure and physiology of vegetables were generally discussed and the Linnaean natural systems of Botany explained. This study seemed to be replete with charms to the native students; Dr. O’Shanghnessy made occasional demonstrative excursions with a portion of the class to the Botanical Garden, and Dr. Wallich. Bramley maintained an international code of instruction then in vogue in France and England – “The admirable effects of the system of concourse in all the medical institutions of France, and where it has been adopted in England, the satisfactory results that have been produced by it, have induced me throughout to adopt it as one of the leading principles of the College, no promotion or reward can be obtained but by a fairly contested examination, where all have an equal chance of succeeding, and wherein the most industrious and deserving are certain of success.[83]

However, Bramley’s unfinished report was finally approved and signed by the high official H. T. Prinsep. The post of the principal was abolished after the death of Bramley, and David Hare was appointed as the Secretary to the College. The College Council was formed of teachers of the CMC – Dr. C. C. Egerton (prof. of surgery), Dr. T. Chapman (of clinical medicine), Dr. McCosh, Dr. Nathaniel Wallich (botany) and Mr. R. O’Shaughnessy (demonstrator of anatomy).

The above formed a Council for the administration of the College. The office of Principal remained in abeyance for nearly twenty years, until revived on ist Feb., 1856, when the title and office were conferred on Surgeon James Macrae, Professor of Medicine. David Hare, however, from 1837 to 1841, was the only non-medical Secretary; his successors being F. J. Mouat, (1841-51), E. Goodeve, (1851-55), and F, N. Macnamara, (1855-56).[84]

It was proposed that the projected Fever Hospital should be united with the Medical College, by which means a highly efficient amount of medical attendance would be ensured to the patients, a t the same time that every requisite facility would be afforded for the instruction of the students. A museum and library had been attached to the College. It was noted, “Contributions to either by individuals or public bodies in any part of the world who wish to aid the progress of European medical science in India, would facilitate the studies of the pupils, and afford them encouraging proofs that this great experiment is regarded with general interest.”[85]

The circuit of “hospital medicine” did find its flesh, life and soul through the functioning of the CMC. Ackerknecht pointed out, “it was only at the hospital that the three pillars of the new medicine – physical examination, autopsy, and statistics – could be developed.”[86] One of the key features of hospital medicine – pathological anatomy – was cultivated in Paris too.[87] In his acute observation, Ackerknecht notes, “These were essentially a consequence of the tremendous influx of uprooted and penniless boys and girls from the country and of the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution.”[88] In later chapters we shall come to see relevance of this observation to an extent for the CMC too – in the newly burgeoning Calcutta.

All the three basic components of hospital medicine – physical examination, autopsy, and statistics – were fully cultivated after the attachment of the clinical hospital to this educational institution. A new medical cosmology and the mode of production of medical knowledge began to germinate and flourish.

[1] Percival Spear, “Bentinck and Education”, in Modern India – An Interpretive Anthology, ed. Thomas R Metcalfe (Delhi: 1994), 240-250 (247).

[2] Ibid, 247.

[3] Eric Stokes, The English Utilitarians and India (1959), xiv.

[4] Ibid., xvi.

[5] Centenary of the Medical College Bengal, 1935 (Calcutta: 1935), 11-12. Hereafter, Centenary.

[6] Report of the General Committee of Public Instruction of the Presidency of Fort William in Bengal, for the Year 1836 (GCPI, 1837) (Calcutta: 1837), 31.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid, 32.

[9] Ibid, 33.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid, 63.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid, 64.

[15] Ibid, 65.

[16] Ibid, 65.

[17] Ibid, 66.

[18] Ibid, 67.

[19] Ibid, 67.

[20] Centenary, 12.

[21] General Report on Public Instruction in the Lower Provinces of the Bengal Presidency, from 1st October 1849 to 30th September 1850 (hereafter GRPI), 123.

[22] GCPI (1837), 64.

[23] Ibid, 36.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid, 37. Italics in original.

[26] Ibid, 39.

[27] Ibid, 39-40.

[28] Ibid, 44.

[29] Ibid, 48.

[30] Ibid, 45.

[31] Ibid, 47-48.

[32] Ibid, 48.

[33] Ibid, 48-49.

[34] Ibid, 49.

[35] Ibid, 49.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Ibid, 50.

[38] Ibid, 50.

[39] Ibid, 49-50.

[40] Ibid, 50.

[41] Ibid, 51.

[42] Ibid, 52.

[43] Ibid.

[44] “The Quarterly Journal of the Calcutta Medical and Physical Society,” Calcutta Monthly Journal, Third Series, III (1837): 16.

[45] Ibid, 16.

[46] Mel Gorman, “Introduction of Western Science into Colonial India: Role of the Calcutta Medical College”, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 132 (3) (Sep., 1988): 276- 298 (296).

[47] Gorman, 296.

[48] GCPI (1837), 51-52.

[49] Ibid, 52.

[50] Ibid, 52.

[51] Ibid, 53.

[52] Ibid, 53.

[53] Ibid, 53.

[54] Ibid, 54.

[55] Ibid, 53.

[56] Ibid, 55-56.

[57] Ibid, 55.

[58] For detailed discussion on this issue see, Jayanta Bhattacharya, “The first dissection controversy: introduction to anatomical education in Bengal and British India”, Current Science 2011, 101(9): 1227-1232. Also see by the same author, “From Hospitals to Hospital Medicine: Epistemological transformation of Medical Knowledge in India”, Historia Hospitalium, Band 28 (2012/2013): 45-74.

[59] Peary Chand Mitra, A Biographical Sketch of David Hare (1877), 127.

[60] George Smith, The Life of Alexander Duff , Vol. 1 (1879), 215.

[61] GCPI (1837), 56.

[62] Ibid, 56.

[63] Pramatha Nath Bose, A History of Hindu Civilization, Vol. 2 (1894), 32.

[64] Shibnath Shastri, Ramtanu Lahiri O Tatkalin Baga Samaj (1909), 158-59. [Translation by me]

[65] David Arnold, Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-Century India (1993), 6.

[66] “The Calcutta Medical College. III”, The Calcutta Journal of Medicine 1873, 6 (6, June 1873): 211.

[67] “The Calcutta Medical College. III”, 211.

[68] R. Havelock Charles, “The Progress of the Teaching of Human Anatomy in Northern India,” British Medical Journal (September 30, 1899): 841-844 (841).

[69] Charles, ibid, 841.

[70] GCPI (1837), 55-56.

[71] Ibid, 56-57.

[72] For a good and precise discussion of the old Calcutta’s different institutions see, Keya Dsagupta, Mapping Calcutta: The Collection of Maps at the Visual Archives of the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta (2009).

[73] GCPI (1837), 57-58.

[74] Ibid, 57.

[75] Ibid, 58-59.

[76] Ibid, 59.

[77] Ibid, p. 59. [Emphasis added]

[78] Ibid, p. 60.

[79] Ibid. [Emphasis added]

[80] “Miscellaneous,” Calcutta Monthly Journal, Third Series, 3.31 (June 1837): 433.

[81] GCPI (1837), 61. [Emphasis added]

[82] Ibid, 61.

[83] Ibid, 62.

[84] D.G .Crawford, A History of the Indian Medical Service, 1600-1913, 2 volumes, vol. 2 (1914), 439.

[85] GCPI (1837), 67.

[86] Erwin H. Ackerknecht, Medicine at the Paris Hospital, 1794-1848 (1967), 15.

[87] Ibid, 74-93.

[88] Ibid, 15.

Mind blowing and authentic describtion. Thanks