Role of pharmacists

The working session Sholmes went to focused on the role of pharmacists in promoting rational use of medicine. Like the nurse, the role of pharmacists in the medical or health systems of many countries is very undervalued. With their training in the science behind modern medicine, pharmacists are critical to ensure quality treatment, patient safety and good health outcomes.

In several countries the training and education of pharmacists also leaves much to be desired. Given their importance to implementing rational use of medicine, many presentations in the session dwelt on ways to improve quality of pharmacists and methods of monitoring their work to help them do a better job.

Ideally, while doctors prescribe medicine it is the job of pharmacists to dispense them after considering various issues related to the interactions between drugs, side effects, proper dosages and even costs involved. However, several countries allow doctors to both prescribe and dispense medicine as this means greater income for the practitioners, who are a powerful lobby influencing state policy.

Two studies were presented showing firstly that community pharmacists were willing to identify and report adverse drug reactions and could be trained to do so. Secondly, counselling by pharmacists increased adherence to medicines and in an example from Sri Lanka showed evidence of slowing the progression of Chronic Kidney Disease of Unknown Origin among rural patients.

A study in Thailand on the curriculum used for training students of pharmacy found it heavily focused on manufacturing pharmaceutical products and providing pharmaceutical care for individual patients. Only a few courses are designed for introducing pharmacy students to practice rational use of medicine systematically i.e. manage the drug supply, monitor consumption, estimate future drug needs, monitor prescriptions, adverse drug reactions and events.

As part of an initiative to design a better course, a group of 7-8 students were assigned to promote rational drug use in an assigned village for three months. Students, faculty members and community leaders worked together to understand drug and health systems in the community before designing a relevant project and performing necessary services. They were guided through the following steps: understanding the community’s needs and problems; prioritizing them; designing a response and then implementing it; evaluating the project; presenting the results to the community; and noting the lessons learnt.

Along the course, pharmacy students had learned that all drug use phenomena were complex as a result of many intercorrelated factors, and a single-linear intervention was not enough to solve the problem.

Sholmes found the project to be fascinating. Without putting your feet on the ground and soiling your hands, no change was possible, he thought. This 3-month project to spend time with the community and tailor a rational use of medicines to match their specific needs was the way forward indeed.

The researchers too concluded in their study that a community-based course with the aim to promote rational drug use in community is a win-win. Students learn various skills in working with real people in real problems to solve the problem systematically, while the community benefits from an intervention designed specifically for them.

However, given the way communities are impacted by decisions taken in faraway national capitals and even by global events or processes, working only at the grassroots will forever remain insufficient. Together with the bottom-up approach there was a need to work on top-down changes also to create the right environment for helping different sections of the population practise rational use of medicines.

Sholmes and Whatsup decided to go together to the next session, which was focused precisely on this theme – the role of governments, policies and systems in improving use of medicines.

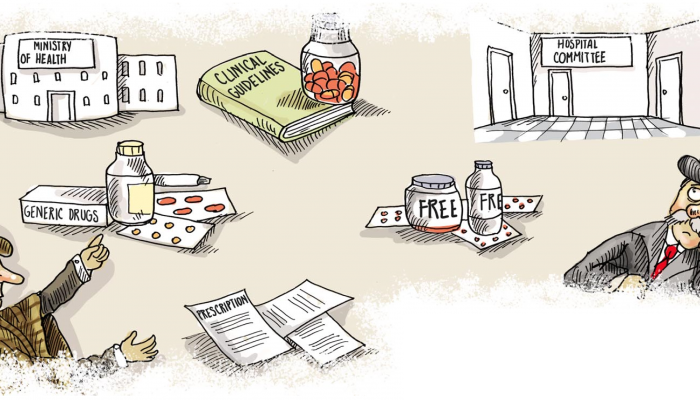

The first presentation of the session was a study to understand which essential medicines policies were most effective in encouraging quality use of medicines in public-sector primary care. It identified a set of essential medicines policies that were consistently associated with better medicines use and recommended their adoption by all countries. These national policies included:

- Having a unit in the Ministry of Health dedicated to monitoring use and promoting rational use of medicines.

- Ensuring use of up-to-date evidence-based clinical guidelines, drug formularies and lists of essential medicines – by distributing them to all practitioners (in paper or electronic format), training all practitioners in their use (at undergraduate and postgraduate levels), and ensuring the drug supply follows the essential drug lists.

- hospital drug and therapeutic committees that can monitor how medicines are used and take corrective actions for misuse.

- generic substitution whereby cheaper generic drugs may be substituted for more expensive branded products,

- regular public education on medicines use,

- medicines free at the point of care in public facilities

- disallowing prescribers to earn money from selling drugs (because this gives an incentive to prescribe more drugs and more expensive drugs)

- disallowing over-the-counter availability of some antibiotics, particularly newer antibiotics reserved for serious infection.

Other presentations showed how individual policies were associated with better use of medicines and patient outcomes. In Russia early diagnosis, implementation of guidelines and protocols led to earlier diagnosis and better medical outcomes in the context of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. In Thailand the Ministry of Public Health launched the Rational Drug Use Hospital Program, covering education of healthcare professionals with monitoring and benchmarking of prescribing and which led to reduction in misuse of antibiotics. In Kazakhstan, development of a national formulary led to a reduction in the use of less effective and more costly medicines.

To be continued…