Preliminary Remarks

Hugh Cagle remarks – “For many in nineteenth-century Europe and the United States, the tropics could be found almost anywhere. Empires actual and aspirational (the United States had no formal tropical holdings until 1898) had already begun to bring the tropics home. Plants, animals, objects, and people from across the tropical world had become the subjects not only of specialized inquiry but also of general public fascination. Crowds at Kew marveled at enormous Amazonian lilies; rhododendrons from India lined a park near the Thames.”[1] Moreover, a skilled goldsmith from India, Rauluchantim, arrived to make finery for the Portuguese Crown. It may be called as the period of “assembling” or “exchanges” in European history supposed to say this. India and the “Tropics” was laid bare before the scientific scrutinizing gaze of Europe, which will later lead into the period of colonization or “exploitation”. This is an intriguing history. It can otherwise be viewed as having been pitched as prefigurations of an epistemic or clinical modernity to come.

N. Pearson finds that “the Industrial Revolution was built on, among other things, fundamental scientific advances in Europe, encouraged by the various learned societies which sprang up in several countries in the seventeenth century. Thus the seeds of later European advance and subsequent dominance must be found in scientific and other achievements, not least in the medical sphere, from at least two centuries before the culmination of the Industrial Revolution.”[2]

Immanuel Wallerstein comments – “One of the crucial elements in the organisation of production in peripheral zones of the world-economy is the guarantee of regular, low-cost labour. Hence the coercion; hence the rnew tenurial relations, hence the increased supervision of the work process. Cash-cropping in India did. not seem to escape this process, and the big transition seems to be the first half of the nineteenth century.”[3]

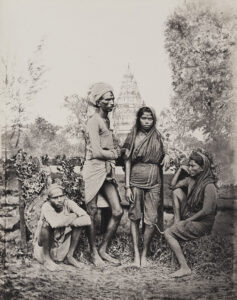

(Symbolic figures show 19th-century India and its medical practice. Source: BBC)

The systematizing of nature, foreign natural world and disease patterns are a European project of a new kind – “planetary consciousness among Europeans.”[4] This process of systematization was to assert even more powerfully the authority of print. With regard to the previous centuries, travel writings of the 19th century took a different trajectory. Mary Louise Pratt calls these places as “contact zones” – social spaces where disparate cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination.[5] It gave way to new form of ideology which created global imaginings above and beyond commerce.

As for Calcutta, political, cultural, academic and economic capital of the then India, Kapil Raj comments – “As the historical geography of Calcutta unfolds, we find the notion of a contact zone transformed into that of an intersection of myriad heterogeneous networks, a node in the transformative circulation of knowledge which structures and organises cultural encounter and its outcome. Through its institutions it also plays a major role in hierarchising knowledge.”[6]

This was a period when knowledge and epistemic exchanges in asymmetrically overdetermined space completely ended. It ushered in the beginning of thorough European hegemony over Indian way of perceiving medical traditions and their translation into practice. It is even clearly evident in the case of “reverse migration” – Indians who settled in England. “While they socialized with each other, they also entered deeply (albeit to different degrees) into British society. They accepted British models for teaching their languages, and also assumed British social roles for themselves as middle-class professionals. Thus, their social position in England and their personal relations with Britons there contrast strikingly with chose of mere hired tutors, a status which many of their peers at Fore William College had to endure.”[7]

Unlike Bernier’s or other travelers’ perception of the preceding centuries (for example), British medicine now demanded unquestionable superiority from Indians. Arnold reminds us – “Western medicine after 1835 (foundation year of the Calcutta Medical College) was taken as a hallmark of a higher civilization, as a sign of moral purpose and legitimacy of colonial rule in India, just as indigenous medical ideas and practices could be easily equated with ignorance and barbarism.”[8] Pratt further argues – “One can glimpse what it is like to imagine “Europe” as also constructing itself from the outside in, out of materials infiltrated, donated, absorbed, appropriated, and imposed from contact zones all over the planet.”[9]

Medicine brought forth autopsy and pathological examination as regular practices. Ironically, pathological anatomy and the practice of dissection did not open the door to cures – hardly any eighteenth-century scientific advance helped heal the sick directly, care of the sick remained marginal. Arnold notes, “Western medicine remained a highly imperfect, empirical science, and for all the pride individual doctors showed in their own skills and nostrums, it was all too evident that when confronted with cholera or dysentery their medicine chests lacked convincing cures.

Even vaccination, a medical technology that largely worked, could not be scientifically explained in the absence of a more developed understanding of immunology.”[10] In 1807, James Johnson prescribed a “unique” combination of medicines for a “liver patient” – “Four grains of calomel, and half a grain, or a grain of opium, to be taken in a little jelly, crumb of bread, or any other convenient vehicle, and repeated every four hours until it sensibly affects the mouth.”[11] For dysentery too, he had used almost the same medications – “the early and liberal use of mercury combined with opium, and a small quantity of antimonial powder, so as to induce ptyalism as soon as possible.”[12]

One thing may be considered here. Social psyche in favor of Western medical practice was, in a sense, an outcome general scientific education started in India during the late 18th and early 19th century.[13]

John Mack., Marshman, Ward, Carrey, Dinwiddie, Stephen Hislop and Serampore missionaries were pioneers to popularize general scientific education. One scholar observes – “a series of scientific instruments sent as a gift from Edinburgh was used by the newly arrived Rev. John Mack, who taught chemistry. By their physicality, these scientific instruments were supposed to impress Indians of the empirical veracity of European science. What mattered was not only what students saw at the end of telescope, for instance, but the rhetorical role played by these instruments.”[14] In describing the ‘grand object’ of Mack’s lectures, the missionaries noted that it was ‘the diffusion among the Natives of a species of knowledge which lays open the real nature of the material objects they so blindly worship’.[15]

Medical education had to overcome two particular problems. First, for more than two thousand years India had its own system of healing grounded on substantial theoretical premise and empirical results of its own. Second, unlike general scientific education, medical education had to specifically base on cadaveric dissection which was of much social repugnance in India. Moreover, in its transformation from the “art of healing” to “biomedical cure”, Western medicine had to incorporate advances in basic sciences. Hence, as a result, Western medicine was not easily introduced here. Travel writings of the 19th century did bear these characteristics in some way or other.

In India, at this particular colonial moment, the British grouped indigenous medicine with literature and the arts “considering it to be a part of local tradition distinct from universal science.”[16] It is consistent with the evolution of the concept and meaning of science in Europe. Science, as a word, came into English in C14. “But from Mc17 certain change became evident. In particular there was the distinction from art.”[17] Understandably, quantification of natural events replaced almost all qualitative aspects of the human world. Attempting to distill disease into medicine-by-numbers, Dr. Brown envisaged a thermometer calibrated upon a single scale, rising from zero to 80 degrees. “The device of a single axis objectified illness into something quantifiable, and pointed to a therapeutics dependent upon dosage size.”[18]

With all these specificities, Western medicine in colonial India had to grapple with so many intersecting therapeutic practices and, consequently, their standardization. Pringle commented, “Another inconvenience… common to all antennas, is the difficulty of making it to standard.”[19] In his experimental spirit of the eighteenth century, Dr. Wade had to admit epistemological mutation of medicine in the colony. While discussing about fevers, John Wade commented, “Doctor Pasly, at Madras, was probably the first who ventured to confide in his own observation, and to deviate from the destructive practice of the times.”[20] He compared his practices in Bengal with those “nosological writers” of England and affirmed, “a comparison of a large collection of cases, which have occurred in Bengal, and on board a ship…will prove to the satisfaction of every person”, if his judgment “is unbiased by prejudices acquired at the university, or in the shop, or by the respect which is due in a certain degree to great names.”[21] Evidently, there was refraction in perception from European medicine in medical thinking among some European surgeons working here.

For the first time in the history of medicine in India individual case records of the patients began to be kept and preserved. In Indian medical tradition, patients had no individual entity. They were, truly speaking, socially embedded. We never find individual patient’s history excepting a few cases in Buddhist medicine. Almost every surgeon had charge of 700 patients. They would keep a regular diary of cases.[22]

For our discussion, 19th century is marked by some important characteristics. (1) During the early 19th century it was the East India Company, rather than the Crown, that ruled India. (2) In hospital practices (for Europeans of India) autopsy became a regular practice to such an extent that, as Harrison argues, “Pathological observations made in military and naval hospitals began to inform new theories of disease causation and course of treatment.”[23] Practitioners working in India had an abundant supply of cadavers. So they were able to compare post-mortem findings with symptoms of disease in living patients “giving rise to a system of medicine not unlike that which later developed in revolutionary Paris.”[24] (3) Anxiety about the disease was rampant during the period. Maybe colonialism was making the “English vulnerable to “foreignness within” as it was producing spaces and peoples in England whose increasing cultural or social “foreignness” provided tropical diseases with a means of invading English society.”[25] (4) We would find differences in presentation of Indian medical knowledge from accommodation to whole scale rejection of Indian medical knowledge as the century rolled on from the phase of consolidation to expansion of the British empire. “In the early part of the following century (19th), the rapid expansion of British territory made possible the creation of pharmacopoeia with an all-India reach.”[26] (5) Science became more comprehensively professionalized and institutionalized “in the work of the colonial medical and scientific services, in hospitals, agricultural colleges and research institutes”.[27]

Early 19th-Century Writings

As already noted elsewhere, there was the regular practice of autopsy. Often these findings led surgeons like Charles Curtis to conclude “That European nosology and definitions, would in India, prove but uncertain or fallacious guides; that a stranger in short, with a good deal to unlearn …”[28] In this case, the knowledge of disease in India dislocated European authority of nosological explanation. He made a distinction between “maritime India” and the rest of India – “what is here stated, applies only to maritime India only, and not to all the variety of inland country comprehended within the vast peninsula.”[29]

Rev. William Tennant noted in 1804 – “though medicine as a science cannot be said to exist among the orientals, many useful observations have occurred in practice, on the effects of various medicines, and their application in different diseases.”[30] He added, “The Hindoos are precluded by their religious system from acquiring any considerable knowledge of anatomy; their chirurgical skill is perhaps, therefore, more deficient than their medical practice; yet it is allowed, thet they perform some difficult operations in surgery; and they are acquainted with sewing up deep wounds, and capable of practicing, what Hudibras has ludicrously termed the Taliacotian art.”[31] He was possibly pointing towards Indian rhinoplasty, lithotomy and couching. He also noted, “There are in all possibility, many medicines which might be useful, were we acquainted with the Hindoo Materia Medica, and the furniture of numerous penzaries, which are open everywhere from Midnapore to Annopsheer.”[32] He found that the “native hospital” of Calcutta to be “so creditable to the humanity and benevolence of the inhabitants of Calcutta”.[33] As a result of “scientific” superiority, “The confidence which the natives, in every trying occasion, put in the superior skill of Europeans, amounts itself to a confutation of those persons, who, without any means of knowledge, are constantly holding up their attainments as superior to every thing (sic.) known in Europe.”[34] He was in all probability talking of Hakeems and Ayurvedics of the time. Rising above their religious proscriptions, he happily noted that “the medical gentlemen in Calcutta are frequently applied to in private by the natives … they generally take their medicines (from English doctors), in spite of their religion.”[35]

William Ward made some interesting observations in 1822. We would remember that the Native Medical institution was established in this year. The institutionalization of Western medical education began to take definite shape from this year on. He exclaimed, “If empirics abound in enlightened Europe, what can be expected in such a state of medical knowledge as that the Hindoos, but that impostors, sporting with the health of mankind, should abound.”[36] He was outspoken about the anatomical ignorance of Indians. “Their ignorance of anatomy, and, in consequence, of the true doctrine of the circulation of the blood, &c., necessarily places their different remedies among the ingenious guesses of men very imperfectly acquainted with the business in which they are encouraged.”[37] He poised a very trenchant question, “What are medicine and surgery without chemisty and anatomy?”[38] It may be profitable to remember what Tytler, then Superintendent of the NMI, taught his students, “no small recommendation for Anatomy … it has a most powerful influence in counteracting prejudices that arise from birth … Before the knife of the anatomist every artificial distinction of society disappears; and if all the individual of the human race are equal in the grave, they are still more so on the dissecting table.”[39]

Regarding chemistry, Ward noted, “Though the Hindoos may formerly have had some knowledge of chemistry, yet it appears to have been too slight to enable them to distinguish the real properties of different substances … Respecting the treatment of fevers, dysentery, and other internal complaints, the Hindoo physicians profess to despise the Europeans … They confess the superiority of Europeans in surgery, however, in all its branches.”[40] Moreover, “They never bleed patient.” He also noted, “The women of the haree cast are employed as midwives; and the doivugnu brahmans inoculate for the small-pox.”[41] He gave an example of a physician feeling the pulse of his patient and diagnosed him to be suffering from fever.[42] He seems to ask a poignant question consistent with his ideological position, “Are these the “benignant Hindoos?” – a people who have never erected a charity school, an alms-house, or an hospital…”[43] We can presume that having laid the foundation of modern science and medicine in his treatise, Ward was now narrowing his focus on the lack of institutions like hospital in India. Ward paid his attention to another aspect of the impact of general scientific and Western medical education in India – “India, thus enlightened and civilized, would, even in an independent state, contribute more to the real prosperity of Britain as a commercial people, by consuming her manufactures to a vast extent, than she does at present, or ever will do, remaining uncivilized.”[44]

In 1832, William Twining, assistant-surgeon of the General Hospital, Calcutta, specifically noted the practice of splenic drainage in Bengal, as described by Lambert in the preceding century. “Long needles are said to be used by native practitioners, to puncture the spleen: and if they ever penetrated to the diseased organ, and a cure succeeded, it is very probable that the successful event might be ascribable to the peritoneal inflammation excited at the diseased part. I have seen them use needles, but so short, that I am quite certain the surface of the spleen was never touched in any of the operations which I witnessed … it is probable that the use of needles for such purpose, is founded on practical acquaintance of the benefits to be derived from such operation when more effectually done.”[45] As distinct from Lambert, Twining, being a surgeon by training, provided physiological explanation of the procedure, “And it is possible that the benefit which is derived from it, may depend on a degree of local inflammatory action, being followed by an effusion of lymph, which on absorption effects a permanent decrease of the spleen.”[46] He added, “Two men now in Hospital, Pereira and Guthrie, have each had the spleen repeatedly and deeply punctured : they are recovering, and 1 think the spleen in each has diminished more rapidly since the operation, than for 3 or 4 weeks previously.”[47]

Montgomery Martin is possibly the first Company surgeon to talk about what we now know as lathyrism. He observed, “It seems to consist in a weakness and irregular motion of the muscles moving the knees, which are bent and moved with a tremulous irregular motion, somewhat as in the chorea, but not so violent. … It is attributed by some to eating khesari (lathyrus-sativus); but this seems fanciful …”[48] In adjacent areas of Purnea, he found about “150 Jurrahs, or surgeon-barbers, who cup, bleed, and treat sores. The midwives are of the lowest tribes, and merely cut the umbilical cord.”[49]

He found that there remained some acts of “hybridization” of European inoculation and Indian variolation. “I have heard that some Europeans have been silly enough to employ them to repeat their spells, even when an European surgeon had performed the operation.”[50] In the surrounding areas of Rajmahal, he found about “20 Jurrahs, who evacuate the water of hydrocele, treat sores, and draw blood both by cutting a vein, and by a kind of imperfect cupping. They are by birth barbers.”[51] On the contrary, medicine was practiced by Brahmins or Vaidyas or Kayasthas. “Medicine (Baidya-sastra) is taught by several of the pundits, some of whom also, although they grammarians, practice the art.”[52] He was pointing towards the contamination European thought by Indian customs on the one hand, and revealed that medicine and grammar are intertwined in Indian medical teaching on the other.

We should note that while the scholastic practice of medicine was vested in the hands of the high caste people, surgical procedures were relegated to the lowest caste and Muslims. The division between medical and surgical practices is quite evident from the big demographic survey done by Martin. Importantly, Ainslie found Hakeems who possess a great deal of information, and are, “in general, men of polite manners, unassuming, liberal minded and humane.”[53]

E. Boileau, lieutenant surgeon of the Company, noticed the practice of indigenous medicine in 1835 in Jodhpur of Rajwara. In his observation, “It is not, however, to be understood that arithmetic is studied or medicine taught as abstract sciences, for the practical part only appears to be attended to each.”[54] By 1835, Western medicine was in a position to claim its hegemony over indigenous ones. Through a series of medical and surgical training experiments in the Native Medical Institution, medical classes at the Sanskrit College and Madrasa of Calcutta, and the School for Native Doctors in Bombay – the period spanning from 1822 to 1835 – Western medical practice was imbibed by especially the upper echelon of Indian society. Boileau affirms, “On another occasion, when the Jesulmer Vakeel was laid up with a fever at Jodhpur, an ordinary dose of calomel and emetic tartar astonished him so that he cleared all the people out of his tent, and assured me solemnly that he was going to die!”[55]

Besides derisive opinion regarding Indian surgical practices the change in tone regarding the use of Indian pharmacopeia also began to change during the mid-19th century. The days of Jones, Ainlslie, O’Shaughnessy or Waring were over. New experiments in the CMC and other institutions were reconstituting British high-handedness of their own pharmacopeia.

H. Irvine wrote, “Nearly all the articles of real efficacy used by the Natives are found in our own Pharmacopoeia, such as gamboge, impure calomel, pure corrosive sublimate, arsenoius acid, senna, cassia fistula, sulphur, mercury, opium, musk, castor, croton, tiglium, rhubarb, turbeth root, jalap, impure potash and soda, the impure mineral acids, and several others.”[56]

In different parts of Rajwara, Irvine noted, “the Jetties conduct the medical and surgical treatment, aided in the latter by the “barbers” who are “surgeons” by caste and occupation.”[57] To him, medicine was as unscientific as elsewhere in Rajwara.[58] Being a surgeon, he was astonished to learn, “Many Europeans in India are still of opinion that native hakims and boeds are often superior in knowledge to, are at any rate are in possession of secrets unknown to, regular practitioners.”[59] He was dismissive about the claim, “I will only instance one among the articles of the native materia medica, than which none is more vaunted, the har or harra, considered to posssess wonderful general deobstruent and purgative qualities, &c, &c., while those who thus belaud it, are apparently not aware that this is the chebulic myrobalan (Termanalia chebula) of our pharmacopoeia of the sixteenth century and long since deservedly neglected.”[60] From today’s point of view, there seems to appear a hybrid space.

He had his own ambiguities in judgment. “The practice of medicine among the natives, is in the hands of Mahommedan hakims, and Hindoo bueds, naies, baburs, and jetties. Their knowledge appears to be at a very low ebb; their chief reliance is upon charms and signs … often the most incongruous and laughable even to themselves …”[61] While he was making such observations of native medical practice he seemed to retain some respect for native surgery which was so long much derided. “The state of surgery is sufficiently good, in the treatment of incised wounds: union by the first intention being almost always effected, the native constitution also greatly aiding in this: the edges of the wound are generally brought accurately together, and the dried skin of the “sambur” is ground very fine with water, and applied in a paste over the edges: this speedily dries and keeps the parts in close contact: the gelatinous nature of application also probably tends to promote immediate union.”[62]

He also found that “Operations for cataract are successfully performed, at times, by travelling oculists, whose employment is hereditary; they know nothing of anatomy whatever; and operate quite fearlessly.”[63] Of the greater operations of surgery, he found, lithotomy was sometimes performed. In his observation, “the lithotomist is as ignorant as the oculist in regard to anatomy”.[64]

The prevailing trend of juxtaposing European surgical superiority and excellence with native surgical ignorance is somewhat dislocated in this observation. The fundamental differentiating point between the two is the knowledge of anatomy. Contrarily, Indian medical knowledge holding its superiority for hundreds of years becomes an issue of ridicule after the discoveries of chemical substances as newer drugs were produced in laboratories.

Again, while commenting on fevers, Irvine himself cuts a sorry figure. “In general the fevers of this district require a considerable degree of depletion to be employed at first, especially in the cases of the young and robust; the degree of depletion being far greatest in the continued, moderate in the remittent, and slight in the intermittent fevers.”[65] Newer chemical drugs of European pharmacopoeia could not provide an answer to the riddle of the much dreaded Indian fever. He stresses on the role of the government and from his entire description it transpires that he was giving his service as a public servant. Seema Alavi cogently notes the “harnessing of the new medical knowledge to the general well being and public service”.[66]

Another important feature began to be manifested in the writings of the travelers. The consolidation of Western medicine with its firm institutional base like the CMC remolded not only travel writings but also a new kind of Indian history. In this line of argument, Colonel Sykes asserted, “the seeds of knowledge we have thus sown fructify to a general and luxuriant harvest, that we shall have left a monument with which those of Ashoka, Chundra Goopta, or Shah Jehan, or any Indian potentate sink into insignificance; and their names will fall on men’s ear unheeded, while those of Auckland, as protector, and of Goodeve, Mouat, and others, as zealous promoter of scientific Native medical education shall remain embalmed in the memory of a grateful Indian posterity.”[67]

In 1844, Stocqeler, wrote, “A visit to the Medical College will well repay the curiosity of the stranger.”[68] In his list of important places to visit in Calcutta was the museum of the CMC. “There are many remarkable examples of tropical diseases of the viscera, ulcerations of the intestines, alterations and derangements of the biliary organs … and some fine preparations of monostrities …”[69] He jubilantly noted, “the science of medicine is freely taught and the qualified practitioners in the healing art distributed over the country.”[70] In his vision, “The blessings of European medical knowledge will gradually extend over the land” and “the ignorant, chicaning empirics, who have for so many years served the office of physicians in India, will be supplanted by a race of men who possess the requisite ability and scientific acquirements to treat disease with a reasonable prospect of success.”[71]

By the mid-19th century Western medicine had generated it legitimacy and extended its tentacles all over India through conduits like dispensaries, different medical schools, jails, hospitals, and, moreover, private practitioners.

R. Bacheler was an American as well as an M.D. He stayed for eleven years in Orissa in the mid-19th century. By that time Bacheler realized “Every European in India being looked upon as a superior being, is supposed to understand more or less of medicine, and is often called upon to prescribe for the sick.”[72] In his analysis, the reason was “The Hindu system of medicine, deficient, and, in many respects, erroneous as it is, is not generally understood even by the majority of native practitioners. Their knowledge does not extend beyond the mere rudiments of the profession.”[73]

Interestingly, only two decades ago, when Boileau finds some amount of dexterity and excellence in low-caste Indian surgery Bacheler simply relegates it to the fringe. “Of surgery they understand little. The blacksmith, with his tongs, serves as dentist, and the barber, with his razor, as surgeon; since these are the only persons supposed to have tools adapted to the practice of these professions.”[74] Bacheler’s account is not interesting only for a derogatory opinion he had about Indian medical knowledge. He also practiced European medicine and surgery in his Mission. These accounts will provide some more aspects of travelers’ account.

Following his account, “Medicines have been dispensed to all who have applied, and surgical operations performed, for the last nine years. These applicants have usually been poor, such as were not able to pay for medical advice. The pilgrims, on their return from Jagarnath, have afforded a large number of patients; and many come from remote parts of the district, as well as from the town and vicinity of Balasore.”[75] Bacheler states, “During the last year, the number of applicants has very much increased, in consequence, probably, of the introduction of chloroform. A few successful operations under its influence seemed to establish the confidence of the people, to an extent never before known, not only in regard to surgical operations, but, also, in the use of European medicines generally.”[76] In 1850, 12 cases were operated under chloroform. It seems quite interesting that in the CMC chloroform was applied by R. O’Shaughnessy within 3 months of its discovery in November 1847 in London. Bacheler applied chloroform in a province far away from Calcutta.

A small medical class was also formed composed of young students from different parts of the province. “They are pursuing a course of study sufficiently thorough, it is hoped, to enable them to practise medicine and surgery with success, according to European principles.”[77]

All these observations make it comprehensible that the model of CMC has begun to operate since the mid-19th century India. “In the absence of medical books, a lecture has been delivered daily, which each student has copied out for future reference ; and these, when the course is completed, will embrace a sufficient amount of information to enable them to perform the duties of their calling with acceptance. They have rendered great assistance in the Dispensary, most of the labor of preparing and dispensing the medicines having been performed by them.”[78] He also noted, “The Medical Class has completed a course of two years study, each student having taken copious notes of the daily lectures, sufficient to provide himself with a competent guide in the ordinary diseases of the country. Twelve young men have, at different times, been connected with the class, only six of whom have completed the course.”[79]

Concluding Remarks

Not all of those, who are mentioned here, were not only travelers but also settled here and taught medicine and other subjects to Indian students. One of the brightest sons of the Calcutta Medical College S G Chuckerbutty Chuckerbutty emphasized – “granting all the praise and honour due to hard-working and intelligent professors, the European medical officers were at best birds of passage, and could not, therefore, permanently improve the position and prospects of the profession out of the service.”[80] In a move to replace these “birds of passage”, internalization of modern medicine was of prime importance. From this point of view, British and European writings of the period too may be deemed as a sort of travel writings.

If we scrutinize the vicissitudes of travel writings of the 19th century we would find some discrete, yet sometimes overlapping, trends in presentation.

First, during the first three decades of the century some amount of acceptance was there for Indian drugs. Though, to say, Indian surgical knowledge was scornfully rejected.

Second, some special surgical practices of Indian low-caste people generated awe within Europeans. Some of these practices included rhinoplasty, lithotomy, couching for cataract, drainage of splenic and other abscesses. But their lack of anatomical knowledge decidedly made them inferior to Europeans. These practices were gradually assimilated within the technically and organizationally all-powerful European surgical practices. Especially, after the introduction of chloroform and ether as anesthetic agents the power and excellence of European surgery had no rivals.

Third, during the later part of the century Indian medical knowledge too had lost its position. Earlier, in Irvine’s writings we found the inkling. Years later, in the Rajputana Gazetteer it was clearly stated, “There are said to be some three thousand different kinds of physic to be obtained from the shops of the pansaris, or native druggists; but, of these, only three hundred are believed in; nearly all are imported from other parts of India. Most of the drugs of real efficacy used by native practitioners are to be found in our own pharmacopoeia.”[81] In Indian context, producing new pharmacopoeia was related to bringing about homogeneity amongst numerous synonyms of Sanskrit, Arabic, Persian and Tamil names, and their regional variations.[82]

Fourth, as we have seen in the case of Martin and Irvine, there were hybrid spaces in disease perception. “Hybrid disease landscapes … upset the stability of of colonial disease geography by questioning and displacing European epidemiological certainties and securities.”[83]

Fifth, in this journey of Western medicine from uncertainty about medical supremacy to the decisive authority of medicine, the CMC played the most important role. Ballingall designated blood-letting, purging and mercury to be “the most powerful resources of the healing art”.[84]

In 1928, Montgomery Martin laid the project and plan of the CMC, which was rejected by Bentinck “lest Hindoo prejudices should be offended”. Within a span of seven years, after experimentations through different college systems of teaching anatomy, surgery and hospital training, the CMC was “in full operation and producing much good.”[85] Against this perspective, travel writings also began to change, as we have seen in the case of Stocqueler.

Post-1857 India represents another pattern of travel writings. We have stopped short of that period. That is another account somewhere else.

Endnotes

[1] Hugh Cagle, Assembling the Tropics: Science and Medicine in Portugal’s Empire 1450-1750 (Cambridge University Press, 2018), p. 3.

[2] M. N. Pearson, “The Thin End of the Wedge. Medical Relativities as a Paradigm of Early Modern Indian-European Relations”, Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Feb., 1995), pp. 141-170 (170).

[3] Immanuel Wallerstein, “Incorporation of Indian Subcontinent into Capitalist World-Economy”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Jan. 25, 1986), pp. PE28-PE39 (PE 32).

[4] Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (London, New York: Routledge, 1992), 29.

[5] Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (London, New York: Routledge, 2008), p. 7.

[6] Kapil Raj, “The historical anatomy of a contact zone: Calcutta in the eighteenth century”, Indian Economic and Social History Review, 48, 1 (2011): 55–82 (78).

[7] Michalel H. Fischer, Counterflows to Colonialism: Indian Travellers and Settlers in Britain 1600-1857 (Delhi: Permanent Black, 2004), p. 116.

[8] David Arnold, Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-Century India (London: University of California Press, 1993), p. 57.

[9] Pratt, Imperial Eyes, p. 134.

[10] David Arnold, Science, Technology and Medicine in Colonial India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004), 66.

[11] J. Johnson, The Oriental Voyager; or Descriptive Sketches and Cursoy Remarks, on a Voage to India and China (London: James Asperne, 1807), 250.

[12] Ibid, 256.

[13] For a good study see, H. J. C. Larwood (1961), “Science and education in India before the Mutiny”, Annals of Science, 17(2): 81-96; “Science in India before1850”, British Journal of Educational Studies, 1958, 7(1): 36-49.

[14] Sujit Sivasundram, “‘A Christian Benares’: Orientalism, science and the Serampore Mission of Bengal”, Indian Economic and Social History Review, 44, 2 (2007): 111–45 (117).

[15] Ibid, p. 136.

[16] Richard S. Weiss, Recipes for Immortality: Medicine, Religion, and Community in South India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 22.

[17] Raymond Williams, Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 277.

[18] Roy Porter, The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present (New York: Harper Collins, 1999), 262.

[19] John Pringle, Observations on the Diseases of the Army in Camp and Garrison (London: Millar, Wilson and Durham, 1753), 233.

[20] John Peter Wade, A Paper on the Prevention and Treatment of the Disorders of Seamen and Soldiers in Bengal (London: J. Murray, 1793), 45.

[21] Ibid, 47-48.

[22] Transactions of the Medical and Physical Society of Calcutta, 1829, 4: 171.

[23] Mark Harrison, Medicine in an Age of Commerce and Empire: Britain and its Tropical Colonies, 1660-1830 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 5.

[24] Ibid, 4.

[25] Alan Bewell, Romanticism and Colonial Disease (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 20.

[26] C. A. Bayly, Empire and Information: Intelligence gathering and social communication in India, 1780-1870 (New Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 272.

[27] Arnold, The Tropics and the Traveling Gaze: India, Landscape, and Science 1800-1856 (New Delhi: permanent black, 2005), 34.

[28] Charles Curtis, An Account of Diseases of India (Edinburgh: W. Laing, 1807), xvi. [Emphasis added]

[29] Ibid, xix.

[30] William Tennant, Indian Recreations, vol. I (Loondon: Longman, 1804), 358. [Emphasis added]

[31] Ibid, 360. [Emphasis added]

[32] Ibid, 363.

[33] Ibid, 73.

[34] Ibid, 74.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Wiliam Ward, A View of the History, Literature, and Mythology of the Hindoos, vol. II (London: Kingsbury, Parbury, and Allen, 1822), 339.

[37] Ibid, 338.

[38] Ibid. [Emphasis added]

[39] John Tytler, trans., Anatomist’s Vade-Mecum (Calcutta: Education Press, 1830), 14.

[40] Ward, A View, 337-338.

[41] Ward, A View of the History, Literature, and Mythology of the Hindoos, vol. I (1822), 96.

[42] Ibid, 269.

[43] Ibid, cvii. [Emphasis added]

[44] Ibid, liii. [Emphasis added]

[45] William Twining, Clinical Illustrations of the More Important Diseases of Bengal, with the Result of an Enquiry into their Pathology and Treatment (Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press, 1832), 332.

[46] Ibid, 332-333.

[47] Ibid, 334.

[48] Montgomery Martin, The History, Antiquities, Topography, and Statistics of Eastern India, vol. I (London: Wm. H. Allen and Co., 1838), 115.

[49] Ibid, 139.

[50] Ibid, 140.

[51] Martin, The History, Antiquities, Topography, vol. II (1838), 106. [Emphasis added]

[52] Martin, vol. I, 137.

[53] Whitelaw Ainslie, Materia Indica, vol. II (London: Longma, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1826), xxxiii.

[54] A. H. E. Boileau, Personal Narrative of a Tour through the Western States of Rajwara, in 1835 (Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press, 1837), 182.

[55] Ibid.

[56] R. H. Irvine, A Short Account of the Materia Medica of Patna (Calcutta: Military Orphan Press, 1848), 2.

[57] Irvine, Some Account of the General and Medical Topography of Ajmeer (Calcutta:W. Thacker & Co., 1841), 25.

[58] Ibid, 30.

[59] Ibid, 153.

[60] Ibid. [Emphasis added]

[61] Ibid, 122.

[62] Ibid. [Emphasis added]

[63] Ibid. [Emphasis added]

[64] Ibid.

[65] Ibid, 114. [Emphasis added]

[66] Seema Alavi, Islam and Healing: Loss and Recovery of self of an Indo-Muslim Medical Tradition 1600-1900 (New Delhi: permanent black, 2007), 91.

[67] W. H. Sykes (1847), “Government Charitable Dispensaries of India, Chiefly in the Bengal and North-Western Provinces”, 10(1): 23.

[68] J. H. Stocqueler, The Hand-Book of India, Guide to the Stranger and the Traveller (London: Wm. H. Allen & Co., 1844), 294.

[69] Ibid, 295.

[70] Ibid, 51.

[71] Bid, 291.

[72] O. R. Bacheler, Hinduism and Christianityin Orissa (Boston: Feo. C. Rand & Avery, 1856), 174.

[73] Ibid.

[74] Ibid.

[75] Ibid, 175.

[76] Ibid.

[77] Ibid.

[78] Ibid, 175-6.

[79] Ibid, 178.

[80] S G Chuckerbutty, “Address in Medicine: The Present State of the Medical Profession in Bengal (delivered on February 3rd, 1864),” British Medical Journal 2 (July-December 1864): 88. Chuckerbutty, Popular Lectures, p. 143.

[81] Rajputana Gazetteer, vol II (Calcutta: Government Press, 1879), 89.

[82] Jayanta Bhattacharya, “Anatomical Knowledge and East-West Exchange”, in Deepak Kumar and Raj Sekhar Basu, eds., Medical Encounters in British India (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2013), 40-60.

[83] Bewell, Romanticism, 48.

[84] George Ballingall, Practical Observations on Fever, Dysentery, and Liver Complaints, as they occur amongst the European troops in India, 2nd edn., (Edinburgh: Adam Black, 1829), 2.

[85] Rober Montgomery Martin, Statistics of the Colonies of the British Empire (London: Wm. Allen and Co., 1839), 305.

Interesting… Darun

Dear Jayanta — Mesmerizing collections of supporting pictures and your weaving style is non pareil ! In your literary compositions – though you are a physician by profession — I can call you — Indian Ackernecht.But to get international recognition — which you deserve without any doubt — you must dishout the essays in English. keep marching –Good luck –nirmalya da.

Fascinating

There are extensive records of autopsies done in CMC in the pathology department from the 19th and early 20th centuries

I had done a search there for material for my MS thesis in 1990

Especially remember the description of dissections of “watering can perineums” of (presumably) sailors with STDs

So rich an article, Dr Jayanta Bhattacharya. You have incorporated findings of well respected medical scientists of different periods and tried to explain the same even for persons like me having no medical knowledge.

I would have benefited more had I had some medical background!

However, I could understand how the English Medical scientists working in India took time to feel the pulses of the Indians, studied and adapted the scientific parts of the local prevalent medical procedures and went on introducing the English system more acceptable to the Indian students and systems.

Wonderful.

Thank you, Doctor.

Thank you!