The Modus Operandi

- Develop ‘surplus pool’ of ill-trained registered and unregistered doctors

Scarcity of doctors (and the resultant high wages) was acting as a deterrent to further expansion of the private healthcare sector during the 1990s. Medical College Regulations, 1999 act was passed to address this problem. This act laid down the specifications to set-up new private medical colleges. It did narrow the gap of required doctors, but failed to achieve the intended goal as the estimated Rs 300 to 400 crore initial investment and an annual recurring cost of Rs 50 crore to run a private medical college proved to be a deterrent. State in response started to dilute the existing norms, especially after 2008. Medical Council of India (MCI) also turned a blind eye to all their shortfalls (in lieu of handful of cash), all justified citing shortage of doctors. So, while between 1980 and 2014, the number of government medical colleges went up from 100 to 189, private medical college numbers jumped from 11 to 215. Over 70% of medical seats added after 1980 in fact belong to the private sector.

But the numbers still did not match the expectations. This is when Niti Ayaog in 2014 decided to upgrade the district hospitals into medical colleges. So, while number of private medical colleges went up from 215 to 260 in 2019, number of government medical college went up from 189 to 279, between the same period, overtaking private medical colleges for the first time since 1990s. This was just reshuffling of existing government resources in the main while facilitating private colleges with incentives to profit more by charging exorbitant capitation fees increased the number of undergraduate medical seats from 53,348 to 80,312 (a 48% jump) in the same span of 5 years. Because of which post-graduate seats also went up by 18,704 (a 65% jump).

Quality of medical education

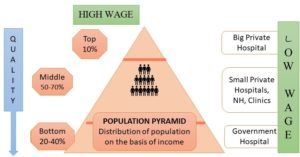

Government medical colleges failed to upgrade their human resources or infrastructure to accommodate these extra medical students, as the standard of both treatment and teaching declined further. Private medical colleges, in addition failed to captivate adequate number of patients because of high cost and poor quality of treatment leading to further deterioration of standard. Such cocktail of fallacies in the medical education system is producing a new breed of ill-trained doctors. This is not an anomaly, but a well thought off intended outcome to produce a surplus of handicapped doctors who could be exploited in either big corporate hospitals as low wage workers, while the rest dissatisfied lot are forced to work in ill-equipped private nursing homes concentrated in urban and semi-urban areas, and government hospitals and health centres. This is mostly not out of choice but out of compulsion because of poor working conditions and low pay structures (in comparison to private sector).

A small elite class of doctors still filters out of the system who either work as relatively high waged skilled labor in big corporate hospitals to treat the rich (including patients who land from outside the country for medical tourism) providing ‘quality’ healthcare or add to the existing brain drain to the rich countries. India in fact is the largest exporter of doctors with more than 47,000 doctors practicing in US and 25,000 doctors in UK. But the irony of the situation lies in the fact that this closed system doesn’t allow the medical students and junior doctors realize these fallacies until it is too late to rectify the problem or even protest against the system which is treating them unfairly.

Figure 3: Majority future generation doctors will end-up as low-wage workers

[1] Current data suggest that little over 10 lakh allopathic doctors are practicing in India to treat 1.3 billion people, which works out to a doctor to patient ratio of 1:11,082. This still falls short of the WHO recommended ratio of 1:1,000. India in fact needs another 5-6 lakh doctors to fill in the vacuum. On a similar note, another 2 million nurses are still required to fulfil the WHO prescribed nurse patient ratio of 1:1483, along with lakhs of primary, community and rural workers.

But, the official target of reaching 1.2 lakh medical undergraduates passing each year which could potentially bridge the doctor-patient gap in the next 5 years is still not sustainable because while State run medical colleges with their existing skewed teacher-student ratio are pushed to their limits, majority of private colleges are on the verge of closing because of their inability to attract sufficient patients essential to run a medical college. Niti Aayog, in desperation proposed a PPP model in November, 2019 to link both new and existing private medical colleges with functional district hospitals. This literal privatization of district hospitals under the coinage of ‘Model Concession Agreement for Setting Up Medical Colleges Under the Public Private scheme’ was placed to bail-out the existing private medical colleges and to incentivize setting of new private medical colleges. District hospitals with at least 750 beds are eligible, out of which 300 + 20% of beds will be free (i.e. State sponsored through insurance), while the rest will provide treatment at market prices. Minimum Rs 10 will be charged from free patients as registration fees. The private party is supposed to pay Rs one crore with an annual increase of only 5% for the first 7 years and subject to a gross ceiling of 50% of gross revenues. Bottom-line remains that the State primary and secondary treatment centres are up for sale.

DEPENDENCE ON MID-LEVEL HEALTH PROVIDERS (MLHP)

Meanwhile, the State in response has also created an artificial dependence on mid-level health providers (MLHP) like AYUSH i.e. the practitioners of Ayurvedic, Sidha, Tibb, Unani, Homeopathy, and Naturopathy who outnumber qualified doctors and are trying to fill in the vacuum. WHO, 2016 estimated that out of all allopathic practitioners, 42% in urban areas and 81% in rural areas are actually not medically qualified. Out of all nurses and midwives practising in rural areas, 33% studied beyond class XII and 89% did not have medical qualifications. National Medical Commission Bill, 2018 brought in the 6-month bridge course to legalize their practise of allopathic medicines in such primary health care setting. WHO recommends that these MLHPs should be part of range of preventive and promotive services, and take part in the curative process only under supervision of trained qualified doctor. But the State not bothered of ‘quality’ of services rendered to the poor, continue to replace qualified doctors with these MLHPs in SCs and PHCs, while the rest majority continue to practise in unregulated private sector with State legitimization. The State in 2017 has in fact identified at least 6 lakh villages who are still completely dependent on such quacks for their primary treatment, with no access to qualified doctor.

(To be continued)

[1] Health Ministry data, 2018