Introduction

“The definition of life is to be sought for in abstraction; it will be found, I believe, in this general perception: life is the totality of those functions which resist death.” (Bichat, 1809: 1. Italics added) Bichat was talking about generalization or theorization in the area of medical knowledge. In describing disease and death, dissection was the potent method to him. He informed, “Dissection and disease exhibit the right and left nervous system of animal life. In palsy one side will be affected, while the integrity of the other side is unimpaired.” (Henderson, 1829: 82) Anatomical dissection was an all- encompassing love in the field of medicine during the late 1780s in America. Anatomists were even tagged with the eponym “brethren of the knife.” (Sappol, 2002: 44-45) On the other hand, in American experience, there was revulsion against anatomists and surgeons from the quarters of medicine. Experience in the use of the knife may, by mere dint of practice, be acquired “by any one (sic) who is not unconquerably stupid…[S]urgeons…undervalue study (of texts), and …attach an unmerited importance to incessant and minute dissection as the only means of acquiring manual dexterity in operating.” (Sappol, 2002: 54)

Hence, following confrontation between medicine and the rising knowledge of anatomy and dissection, it is wise to say, men needed a theory, for the phenomena that come under observation are so numerous that in default of a theory they would elude our grasp. Medicine must be guided by a theory, for otherwise medical doctrine could not be handed on from teacher to pupil. Henry Sigerist, the doyen of history of medicine, remarked, “Every theory is philosophical in its nature. It works with the thoughts, with the concepts, available at any particular epoch, thus moulding the culture of the time.” (Sigerist, 1958: 15) However, there was a time when medical men entertained so determined a dislike to the word theory, that they could scarcely tolerate the term. When also in the prosecution of anatomical enquiries doctors became lost in astonishment that such important ends could be effected by apparently such simple means. (Abernethy, 1814: 15) Interestingly, though talking about anatomical dissection at its most crude and experimental level Abernethy did not fail to take note of the Great Chain in Christian belief. He let us know, “Mr. Hunter, who so patiently and accurately examined the different links of this great chain, which seems to connect even man with the common matter of the universe, was of this opinion.” (Abernethy, 1814: 17) The area of theory is often very fuzzy with other connotations and purposes and not a clear-cut zone. Beclard was astonished to learn that Bichat “with that independence of opinion” so often brought forward in his General Anatomy “those old ideas, which for two thousand years have continued in the schools, those words vital force and vital properties, abstractions which he seems to have taken for realities, to which he gave a separate existence, and which he made perform so important a part in the animal economy.” (Beclard, 1823: xi-xii)

Anatomical knowledge, especially knowledge gained from dissecting a cadaver, was the “Midas touch” which ushered in a new era of medicine. It universalized ‘modern’ medicine and made it the only source of practical as well as theoretical knowledge of the body. All other medical knowledge (traditional and indigenous) was made subservient to it. Importantly, the edifice of modern medicine was constructed over this new theoretical backbone. Anatomy has a long and checkered past as a scientific discipline. Its heyday came in the 19th century, with the development of quick, effective surgical techniques on the battlefield and, later, the introduction of anesthesia, when knowledge of the structural intricacies of the body began to have practical significance for doctors. (Schaffer, 2004) A new norm and epistemological structure began to emerge. J. F. Lobstein remarked, “it is not the dead organ that medicine wishes to understand, but the living organ, exercising the functions peculiar to it…” (Castiglioni, 1947: 691) Knowledge of the living came out from knowledge of the dead.

It may be recollected that the body (in Western culture) since Aristotle’s time was worthy of attention for its own sake, not merely as a means of achieving medical purposes, and anatomy became a discipline, with its own methods of procedure, and formalized within a framework of teaching. No contribution was made in the early Western middle ages to the medical sciences of anatomy and physiology. Curiously, the “knowledge” of the learned consisted of strangely metamorphosed relics of ancient learning in literary and pictorial forms. Only at the end of middle ages do “we find the production of new knowledge from observation taking a considered place in anatomical studies.” (French, 1978: 439)

New Medical Knowledge and Epistemology

It was this new knowledge which differentiated two classes of physicians – modern and physicians like Hippocrates, Celsus, Aretaeus, all the Greek authors. The latter “have been satisfied with observing the symptoms; and consequently most of their diseases are badly described.” (Bichat, 1827: 15) Around 1800 one began to follow Bichat’s (1770–1801) maxim “open up a few corpses”, as Foucault laconically remarks. (Foucault, 1994: 124) In fact, there would be no reason to study inanimate cadavers if disease is a disorder of the circulating humors (Hippocrates or Galen). Nonetheless, if disease is conceived of as a malfunction of parts or forms, like organs (Morgagni), tissues (Bichat) or cells (Virchow), “opening up a few corpses’’ becomes accepted, as theorized by Foucault. The latter attributed the new paradigm to Bichat, in which ‘Dissecting anatomy’ would play a special role, by guiding the medical focus to look for the space where diseases really act, thereby founding modern medicine. (Pompilio and Vieira, 2008: 1)

Dissection-based anatomical analysis facilitated the classification of bodily components, the development of a vocabulary for describing the body with clarity and precision and mapping the bodily organs and their surface projections, which would be later used in physical diagnosis. (Older, 2004) Again, coming back to Bichat, we should “dissect in anatomy, experiment in physiology, follow the disease and make the necropsy in medicine; this is the three fold path, without which there can be no anatomist, no physiologist, no physician.” (King and Meehan, 1973: 532)

Arguably, “medicine itself is not a science: in its epistemological spirit, it is rather a kind of ideology.” (Osborne, 1998) With this line of argument, it may be deduced that anatomical knowledge of dissection is not only a medical knowledge; it is an ideological tool for building new paradigms of the body, health and disease. Furthermore, from a philosophical point of view, anatomy is not merely the structural biology of human species, which happens to be human. Because we are self-aware, the study of the human has a unique place in establishing the image we have of ourselves; ultimately, the prosaic descriptions of the bones, muscles, blood vessels and neural pathways are the context of our experience of life. (Bannister et al, 1995: 2) Dissecting room also becomes a place of “epistemological exhaustion.” (Warner and Rizzolo, 2006)

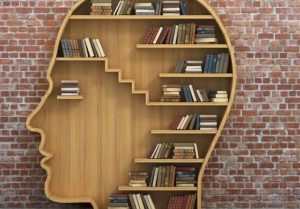

Modern medicine/biomedicine has passed through paradigmatic shifts. Before the advent of anatomical knowledge the working model of the body in medicine was of two- dimensional nature – symptom > illness. Patient’s history alone was the primary source of diagnosis. Though the bodily organs were described, detailed and used to explain disease causation no pathological anatomy was known. Accurate localization of diseases inside the body was inconceivable. As an outcome of emphasis on dissection and experimentation, medicine, during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, made its journey from Bedside medicine to Hospital medicine to Laboratory medicine (and, now, Techno-medicine). (Ackerknecht, 1967; Gelfand, 1980; Hannawaya and La Berge, 1999) Disease appeared to being located within a three-dimensional body –

symptom > illness > sign. Depth or volume of the body – the 3rd dimension – was added to symptom > illness perception whereby the body emerged to be of three-dimensional nature. Doctors were, then, to extract sign, i.e. pathology inside the body. Pictures shown below would help us to get at the point.

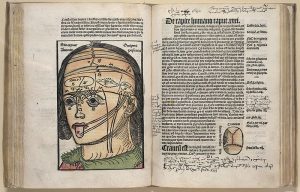

Fig. 1 Magnus Hundt’s Antropologium de hominis dignitate, natura et proprietatibus, de elementis, partibus et membris humani corporis. (Leipzig: Wolfgang Stöckel, 1501). [Antropologium, published in Leipzig in 1501, serves to explain the body not only anatomically and physiologically, but philosophically and religiously too. Humans were created in the image of God and represent a microcosm of the world as God created it.

Courtesy: Historical Anatomies on the Web, National Library of Medicine, US.]

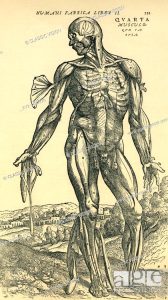

Fig. 2 Three-dimensional body and its different muscles accurately laid bare.

[From Andreas Vesalius’ De corporis humani fabrica libri septem. (Basel: Johannes Oporinus, 1543): 368. He was the anatomist to illustrate human body and its internal organs in a truly three-dimensional way and without any religious or philosophical connotations.]

Other implicit features of this new knowledge of anatomy were – (1) it not only had to be a highly visible knowledge, but also (2) it had to be a true scientia, based on demonstration, and (3) the only demonstrative method available to the dissecting physician was ocular demonstration. (French, 1993: 89) There was a change from old knowledge of the body to an anatomy involving dissection of the muscles, nerves and vessels, as opposed to the simple demonstration of the organs of the three cavities of the body. (Kellett, 1961: 105) It led into the loss of the Physicians’ learned and rational medicine from medical purview. An academic consideration of the ‘Institutes’ in parallel with the new vigorous growth of surgical gross anatomy began to burgeon. (French, 1993) In a more precise note, “The fundamental characteristic of medicine in the 19th century was the attempt to correlate discoveries in the laboratory and the autopsy room with observations made at the patient’s bedside.” (Elizondo-Omana, Guzman-Lopez and Garcia-Rodriguez, 2005: 12)

Despite this, tension between empirical facts and theorization, as noted above, was a much-contested ground during the formative period of modern medicine. Theorization was often used to unravel divine truth in human body and the world. Again, empirical facts were poised vis-à-vis theorization. Theorization was a problematic area in French medicine too. Even a person of Laennec’s stature (the inventor of stethoscope) regarded theories as only aids to memory. In his course of 1822, he even went so far as to say that only facts constituted science. (Ackerknecht, 1967: 9) Louis abstained from formulating hypotheses. “True science is but a summary of facts [which] are of no value if they are not enumerated.” (Ackerknecht, 1967: 10) The best generalization was the numerical method.

The new norm and epistemological structure, which began to emerge through the rise of Hospital medicine, was characteristic of some everlasting transformations of medicine. The tension between theory and empirical facts were resolved through (a) accumulating numerous facts to build a new theory, and (b) applying this theory to immediate clinical, surgical and pathological practices. To speak precisely of Hospital medicine “Actually it was only in the hospital that the three pillars of the new medicine – physical examination, autopsy, and statistics – could be developed.” (Ackerknecht, 1967:

15) Not only so, this new type of medicine was also “the closing hour of medical medievalism.” (Ackerknecht, 1967: 33) [Emphasis added]

The characteristics of this medicine that gave it this prideful place comprised of – (1) the rise of pathological anatomy, or the systematic correlation of clinical observations of the external manifestations of disease with the lesions found in the organs at the time of autopsy; (2) the transformation brought about in clinical observation by its being made not just on dozens of cases but on thousands; (3) the change in clinical activity from primarily listening to the patient’s story to making an active physical examination of patients through large-scale application of new and revised methods of diagnosis, i.e. percussion, auscultation and, most notably, the appearance of that symbol of modern medicine, the stethoscope; (4) the hospital as the locus of medical activity and research, and (5) the use of medical statistics in the analysis of case histories and the evaluation of therapy. (Hannaway and La Berge, 1999: 4)

The transformation of the eighteenth-century hospitals into “curing machines” was itself a complex occurrence involving shifts at many levels. The increasing hospitalization of the poor during the eighteenth century was certainly related to the process of urbanization and industrialization. (Rose, 1999: 59) Clinicians no longer simply saw sick individuals, they saw diseases. Interestingly, “Every time the stethoscope was (and is) applied to patient, it reinforced the fact that the patient possessed an analysable body with discrete organs and tissues which might harbour a pathological lesion.” (Armstrong, 1999: 24)

The use of corpse as teaching and experimental material bears a close relationship to the use of the lived body. For the study of anatomy and of surgery, it is necessary for the practitioner to develop – even to cultivate – clinical detachment while work is in progress. In the case of the dead body, this may be accomplished with comparative ease, in so far as once dead, the human body – whatever the popular culture of the era – may be much more readily objectified than the screaming writhing body of a living patient. The ease of objectification provides an underlying reason why in the 1830s anatomy, and partially dissection, was promoted as constituting the basis of all scientific knowledge of the human body. (Richardson, 2000: 50) Clinical detachment had transmuted the object of veneration and supernatural power which the corpse was in popular culture, into an object of scientific study. This special knowledge of anatomy and dissection, with its subsequent application to surgery, was too authoritative, at least during its germinative period. Hunter is an example in this regard. “Hunter himself appears to have been impervious to ethical criticism, and despite mounting clinical evidence, he continued to deny clinical failure and to cast doubt on stories of disease spread.” (Richardson, 2000:

411) The discoveries of the Hunters and their disciples had, however, confirmed the centrality of anatomical dissection as the foundation of medical and surgical education and it was an experience all students underwent. (Stanley, 2003: 170)

To emphasize, although pathological anatomy, exemplified by the earlier work of Laennec, François Broussais and others and by the ongoing research of Jean Cruveilhier, remained a central focus of Paris medicine, physicians investigated new diagnostic approaches. The notion emerged that one could dissect and analyze organs, tissues, and body fluids to find disease. (La Berge, 1999: 278)

Salient Features of Modern Medicine

It would be not an exaggeration if one asserts that it is anatomical dissection which has made medicine ‘modern’. That is why New England Journal of Medicine, while “Looking Back on the Millennium in Medicine”, places Elucidation of Human Anatomy and Physiology in the first place among the ten most important achievements of medicine in the last millennium. (Brenner, 2000: 42-49) Joseph Leidy expressed similar view one and half centuries ago. Leidy told in his lecture, “The practice of medicine of the ancients was an art, and not a science, and dignity it did not acquire until it was based on acquaintance with anatomy and physiology.” (Leidy, 1859)

Anatomical dissection without the aid of knife is not conceivable. The question of knife will become apparent when we enter into the area of Indian anatomy. Changes in the culture of medicine have carried anatomy from a research science, to a training tool, nearly to a hazing ritual, to a vehicle for ethical and moral education. Physicians, scientists, and medical students, as well as observers such as sociologists and writers, have been only intermittently aware of these cultural shifts. Yet anatomical dissection has been a remarkably persistent feature of medical education – indeed, it stands out as the most universal and universally recognizable step in becoming a doctor. (Dyer and Thorndike, 2000: 969) Compulsory study in gross anatomy works is no doubt the initiating rite of the newly arrived into the professional tribe of physicians. In the early period of anatomy teaching, the professor lectured from a chair elevated above the cadaver while lowly barber-surgeons demonstrated various structures at the professor’s command. Students were completely passive – they engaged the dissected body only through their eyes and their ears, never with their hands. (Gregory and Cole, 2002)

In the later period, anatomy teaching has passed on from “a necessary inhumanity” to commencement of clinical medicine with anatomical dissection. (Aziz et al, 2002) Anatomy is widely appreciated as being among the most significant components of medical education and the study of anatomy through the dissected cadaver is viewed as the uniquely defining feature of medical courses. (McLachlan and Patten, 2006)

Significantly, dissection-based anatomical knowledge is also associated with metaphors of invasion (Otis, 1999), new subjectivity of modernity and professional identity (Sappol, 2002: 2-7). Metaphor was used in other ways too. In the 18th century, when doctors turned to mathematics to produce a Newtonian map of the body, the metaphor of hydraulic pumps was used to express human digestion and blood circulation. (Turner, 2006) To continue, dissection broadened the gulf between the rich and the destitute of a society. Moreover, it also legitimized the state and institution’s claim to the pauper’s body. (Richardson, 2000) Anatomist’s and physician’s perception of self gradually transformed into a secular, individualist, unitary, self-bounded, internalized and modern self. It was no more the perceived self of the population, which again, in its turn, reconstituted the self of the population. “The body was the anatomist’s stage, upon which he outlined a complete text.” (Sawday, 2006: 131) Over this text, a few important chapters of medical knowledge and its history were written forever – (a) evolution, manifestation and organ localization of disease, and (b) application of anatomical knowledge into surgical practice. Western medicine originated, in large part, from the practice of autopsy, which led to the first insights into the connections between a patient’s clinical symptoms and diseased organs found after death. (Soulder, Terry and Mrak, 2003) By correlating the clinical anatomical findings, physicians defined diseases, achieved greater precision in diagnosis, and began to appreciate disease-as-process implying that diseases underwent development, in which the time factor was important.

This “complete text” took a different shape when it was dislocated from its origin and transplanted into the soil of colonized land. Both race and sex were a product of ‘deep’ forms of knowledge, such as pathological anatomy, “which began to emerge at the end of the eighteenth century, in contrast to ‘Linnean’ forms of natural history which were concerned with classification on the basis of surface appearances.” (Harrison, 1999:

12) The body, though firmly located in colonial India, was scientifically observable only through knowledges and practices of colonial medicine which developed different and conflicting ideas about diseases and their treatment. “The new discipline privileged etiology over pathology, which permitted it to analyze disease as the product of a microbe’s combination with the tropics.” (Prakash, 2000: 137. Emphasis added.)

Colonial diseases darkly mirrored English social space. “The “Foreign” diseases that the British were encountering outside their island seemed to reflect a foreignness within. In a world where the boundaries of colonial contact had become fluid…” (Bewell, 1999: 51) What is important here is the concept of bounded, stable and circumscribed self of modernity to the formation of which anatomical knowledge plays a significant role begins to dissolve, when it gets dislocated to the colonial world far away from its origin. Despite this, it was obviously mandatory for the colonial ruler to sustain their superiority in all branches of knowledge, particularly in science and medicine. In Indian context, Western medicine derived its “claim to scientific objectivity and authority largely from…studies of morbid anatomy…” (Arnold, 1993: 53)

Terms and images plucked from the colonial language of medicine and disease began to infiltrate the phraseology of Indian self-expression (or, put otherwise, Indian subjectivity), to become part of the ideological formulation of a new nationalist order. (Arnold, 1993: 241) These terms and images were firmly anchored on superiority of anatomical knowledge, excellence of surgical practices and, at a later period, diagnostic and therapeutic marvels.

Against this backdrop, an interesting episode in the history of medicine was waiting to be unveiled.

No Anatomist, No Knife – Indian Surgical Knowledge and the Body

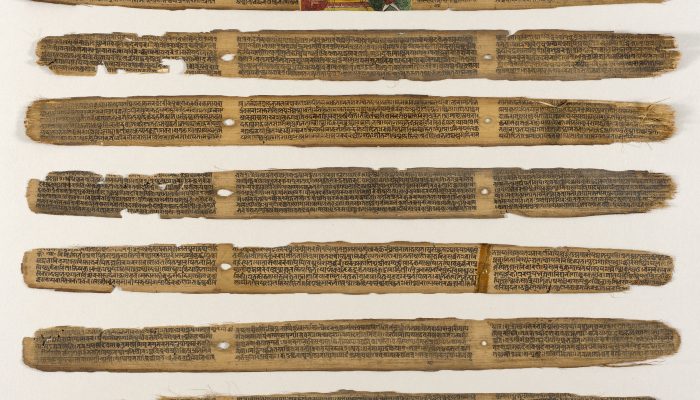

The Greater Triad of Āyurveda comprises Caraka (Saṃhitā), Suśruta (Saṃhitā), and Vāgbhaṭa (Aṣṭāńgahridayasṃhitā). Among them, the Suśruta is renowned for his elaborate discussion and practical instructions on surgery and, even, preparing a dead body for teaching purpose.

(Los Angeles County Museum of Art published on 11 January 2018. These palm leaf manuscript was originally found from Nepal, text is dated 12th-13th century while the art is dated 18th-19th century.)

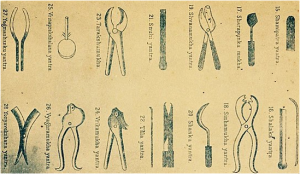

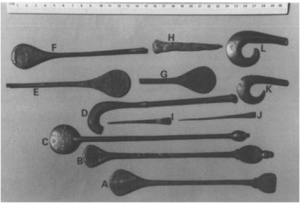

(Later reconstruction of instruments, fully attributed to him and supposed to be used by Sushruta himself. See below too.)

(Accepted as Sushrutan Instruments: Historical and Now: NO Sushrutan Instruments by EBD i.e. Archeology. “recipe” only. National Museum of Pakistan. showing ancient IVC tools and instruments (attributed to Sushruta). These instruments have been used in various modern texts time and again. But such accurate instruments were designed by Sushruta is untenable.)

The Suśrutasaṃhitā (Āchārya, 2008) consists of eight chapters – Sūtrasthāna, Nidānasthāna, Śārīrasthāna, Cikitsāsthāna, Kalpasthāna, and Uttaratantra. Importance of surgery is expressed thus – “It is pre-eminent too on account of its quick action, owing to the use of sharp and blunt instruments (śastra, yantra), caustic (kṣāra), and cautery (agni). [Sū, 1.17-18] (Meulenbeld, 1999, IA: 203)

The crucial problem arises with a mnemonic verse of śārīrasthāna (5.46) – tvakparyantasya dehasya yohyam ańgaviniścayaḥ // śalyajñānādrite naiṣa varṇyatehańgeṣu keṣucit // (In English translation – “Foetus lies woman’s uterus in state of universal flexion facing mother’s back; at the time of delivery, it comes naturally to vagina with head.”)

Everyone from Hoernle to Meulenbeld has translated this passage as containing knowledge about the body, i.e., anatomical knowledge. Here, the basic problem erupts with the term śalyajñānād. This term is usually accepted for anatomical knowledge. Only exception is Fiser and Fiserova’s article (Fiser and Fiserova, 1963). They are unhappy with such translation.

Śalya actually means “a dart…shaft (also the point of an arrow or spear and its socket), anything tormenting or causing pain…or (in med.) any extraneous substance lodged in the body and causing pain…and, as a branch of medicine, to ‘the extraction of splinters or extraneous substances’….” (Monier-Williams, 2002: 1059) In Apte’s dictionary the fifth meaning of śalya is “Any extraneous substance lodged in the body and giving it very great pain.” (Apte, 1985) All these meanings are relevant for a surgeon (śalyahartar) in India. To some authors, “It may as well be added that they (surgeons) were perfectly acquainted with the anatomy of the goat, sheep, horse, and other animals used in their sacrifices.

Early warfare was conducted with such weapons as bow and arrow, sword, mace, etc. Thus in every war the services of bold and skilful surgeons were always in requisition for extracting arrows, amputating limbs, arresting haemorrhage, and dressing wounds.” (Sinh Jee, 1896: 179-180. Emphasis added.). Emphasis added.) Kunte observed, “surgeons … extracted the shafts of arrows lodged in the body and dressed wounds which the ancient Āryas dreaded much, because, before they went to war, they donned coats of mail, cuirasses and helmets.” (Kunte, 1902: 4) Now it may be prudent to remember Edelstein, “In antiquity, knowledge of the body is never exclusively professional knowledge, as it is now.” (Edelstein, 1987: 261)

The next mnemonic verse of śārīrasthāna (5.47-48) sheds light on “certain (niḥsaṃśaya) knowledge” of anatomy. Meulenbeld translates the passage, “A surgeon (śalyahartar), who wants to acquire certain anatomical knowledge, should, with that in mind, thoroughly examine a dead body, after cleansing it, for increase of knowledge arises from the combination of perception (pratyakṣa) and study of the science.” (Meulenbeld, IA: 253) The verse is –

tasmānniḥsaṃśayaṃ jñānaṃ hartrā śalyasya vāñchatā // śodhayitvā mṛtaṃ samyagdraṣṭavyohańga viniścayaḥ // (47) pratyakṣato hi yadṛṣṭaṃ śāstradṛṣṭaṃ ca yadbhavet // samāsatastadubhayaṃ bhūyo jñānavivardhanam // (48)

Here too remains the problem of translation. In Fiser and Fiserova’s translation, “Therefore, anyone who strives after acquiring a safe knowledge of śalya, must prepare a dead body, and examine its parts in the right way.” (Fiser and Fiserova: 313) We have seen before that śalya should not be confounded with anatomy. This term is more concerned with surgery. Moreover, Hoernle provides us with a varia lectio in Bodleian MS., No. 739 and India Office MS., No. 1842. The variant reading is – icchatā śalya- jīvinā, instead of śalyasya vāñchatā. (Hoernle, 1994: 225-226) It clearly denotes a physician who lives on surgery (śalya-jīvinā).

Zysk points out to the fact that “a violation of the dead person’s sacredness seems prposely to be avoided that rather than cutting into the corpse with a sclapel (śastra)…Suśruta instructs that practice should be carried out on fruits, gourd skin, water- bags, stalks of plants and the like.” (Zysk, 1983: 188)

It points towards the presence of a surgeon, not an anatomist. If this is the situation, we have to confront and resolve a few questions – (a) how this knowledge of śalya was practiced, (b) without having knowledge of anatomy how ancient physicians or surgeons managed to do surgery, and (c) how it came to an end.

After the mnemonic verses, the next part of śārīrasthāna is composed in prose. In ancient medical texts, mnemonic verses were written for memorizing theory, while practical lessons were written in prose. In the next prose section there is thorough discussion on how to prepare a dead body for dissection – “For this purpose, a corpse should be selected which is intact, originating from a person who has not died from poison, has not suffered from a disease for a long time, and has not lived until a very old age. [The text has avarṣaśatika, i.e., one who has not attained the maximum span of life of hundred years. (Meulenbeld, IB: 375, note 151)]

The corpse, with the intestines and their contents removed, should be wrapped in coverings of muñja grass (botanical name – Tripidium bengalense, bark, kuśa grass (botanical name – Desmostachya bipinnata), śana (hemp), or any other suitable material, and placed in a running stream, kept within a cage (pañjara), at a place where it is not easily noticed; it should be left there in order to decompose; then, after seven days, one should take it for examination, very gradually scrapping away all the tissues, beginning with skin, and, subsequently, the major and minor external and internal parts of the body which have been mentioned; the scrapping away should be carried out by means of a brush (kūrca), made of uśīra grass, animal hairs (bāla), veṇu (bamboo), balbaja grass (botanical name – Eleusine indica), or any other suitable material. (5.49)” (Meulenbeld, IA: 253)

Such particular procedure by scraping the layers one by one of a dead body after purification is called avgharṣaṇa. Similar method of preparing a dead body, named hydrotomie, has been found in European experience too. (King and Meehan, 1973; Mazars, 2006) Curiously enough, it may be mentioned that there was the use of black ants whose mandibles serve as staples for suturing a wound. (Mazars: 70-71) Rahul P. Das cites reference from later texts on the particular procedure of avgharṣaṇa in later Āyurvedic text of Vāgbhaṭa (Sūtrasthāna, 34, 38). (Das, 1983)

What is missing in this entire discussion is the use of any knife. The described way of treatment without the use of a knife by a simple scrubbing with a whisk made of the roots of Andropogon muricatus (uśīra grass). Fiser and Fiserova note, “there is no other instance of a dissection without knife, known so far.” (Fiser and Fiserova: 316) However, in sūtrasthāna of Suśrutasaṃhitā there are mentions of śastra-s and yantra-s. (Sū, 1.7 and 1.8)

Various types of knives are described there. For our present purpose, we are concerned with the use of knife only in case of dissection. Following instruments are accepted as Sushrutan Instruments: Historical and Now: NO Sushrutan Instruments have been found Archeology. “recipe” only. National Museum of Pakistan. showing ancient IVC tools and instruments (attributed to Sushruta). These instruments have been used in various modern texts time and again. But such accurate instruments were designed at the time of Sushruta or by himself seems to be untenable.

Now, the relevant question comes up – what could the ancient Indian physicians and surgeons actually observe by employing the described method of dissection? We have some plausible answers – (1) this kind of examination of human bodies provides the dissecting surgeon with some amount of rough information on soft tissues, and (2) he could possibly examine the tendons, ligaments, vessels muscles etc. wherefrom he could be able to get an idea of their course. “Nevertheless, he could not distinguish them from each other, and estimate their physiological functions; he merely learned that these structures are not to be damaged in the course of an operation.” (Fiser and Fiserova:

- Emphasis added.)

Here remains an answer to our previous question – without having the knowledge of anatomy how the ancient physicians or surgeons managed to do surgery. Kutumbiah explains the problem, “Surgical operations demanded a knowledge of regional anatomy rather than elaborate and often tedious description of all the structures of the body. The place of regional anatomy was supplied by the concept of marmas.” (Kutumbiah, 1999: 33) Marmas or marmans should be understood as vital/lethal points arising out of a junction or meeting place of the five organic principles of ligaments, veins, muscles, bones and joints. There are one hundred and seven marmans. Heart, head and basti (urinary bladder) are known as ‘trimarma’ because of their importance. (Sharma, 1998:

16) Filliozat notes, “It is equally from a Vedic conception in preserving the corresponding Vedic name that classical medicine has elaborated one of its most characteristic notions of anatomy, that of the vulnerable points or marman.” (Filliozat, 1964: 163) The form is derived from the root mr, “to die”, and it means above all a “mortal point”. The Āyurvedic texts have an extremely detailed catalogue of the marmans and they are, in general, quite easily identifiable, thanks to the precisions that are furnished. “They are most often the big vasculo-nervous packets or the tendons and the important nervous trunks.” (Filliozat, 1964: 164)

It is obvious that this type of surgery is a craft, even being bereft of precise knowledge of anatomical organs. In Indian context, where education was based on gurukul system, some dexterous surgeons could carry this craft on to their pupils in a non-institutional family setting. Gradually, through accumulation of knowledge and its practice over many years, one could become a gifted surgeon (not in the shadow of modern medicine). Such kind of surgical dexterity was palpably present even during the colonial period in India. We shall examine this issue later on.

Now we can try to address the question of decline of surgery in India. Zysk has convincingly argued about Hinduization and Brahminization of Indian medicine. (Zysk, 2000) Chattopadhyaya also provides some insights into this issue. (Chattopadhyaya, 1977)

One of the most authoritative Brahminic text the Manu Saṃhitā (Laws of Manu) states, “The food of a physician is (as vile as) pus, that of an unchaste woman (equal to) semen, that of a usurer (as vile as) ordure, and that of a dealer in weapons (as bad as) dirt. (4.220)” Manu Saṃhitā was composed around 200 A.D. or later. (Sharma, 1996: 17) Dasgupta comments, “A comparison of Suśruta and Vāgbhaṭa I shows that the study of anatomy had almost ceased to exist in latter’s time.” (Dsagupta, 1991: 433) As a result, there arose problems of interpretations of ancient medical terms. (Dasgupta, 1991; Das, 2003; Filliozat, 1964; Jolly, 1977; Meulenbeld, 2008; Wujastyk, 1998; Zimmermann, 1999) We should be aware of the fact that these ancient context-sensitive polysemous terms should not be read back with a post-Renaissance, post-Vesalian and post-Harverian mindset. Assaying scientific nature of Āyurveda, supposed to be distinct from the religious Vedas, Engler argues, “Ayurveda simply does not manifest characteristics of modern science in anything more than a vague analogous sense.” (Engler, 2003: 429) While discussing elements of ritual practices in Vāgbhaṭa’s text, Benner finds “It is therefore not always possible to clearly and sharply distinguish ritual and medicine.” (Benner, 2009: 132)

Interestingly, after the full discussion on how to prepare a dead body for medical knowledge and training we find in śārīrasthāna (5.50) –

na śakyascakṣuṣā draṣṭuṃ dehe sūkṣatamo vibhuḥ /

dṛśyate jñānacakṣurbhistapaścakṣurbhireva ca // [The vibhu (ātman), being extremely subtle, cannot be perceived with (normal) eyes, but only by means of (the sight acquired through) spiritual knowledge (jñāna) and penance (tapas).] (Meulenbeld, IA: 253)

Zysk finds Suśruta “Speaking in terms of Vedānta (as interpreted by the 14th cent. commentator Ḍalhana)” and “exposing the internal parts of the human body will never reveal (or harm) the inner soul or self (Ātman) whose correct understanding is gained rather from the religious practices pertaining to sacred knowledge and from ascetism.” (Zysk, 1983: 188) Vibhu is Ātman, the spiritual self of Vedānta.

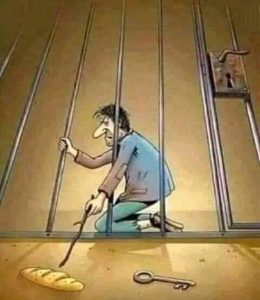

With this passage in mind, it is understandable that spiritual knowledge finally overshadows the craft of dissection. Embedded within such a social milieu in ancient India, surgical practice was relentlessly relegated to the margins and to the low-caste people like barber potter etc. High caste physicians would only practice textual and scriptural medicine, without ever touching the body. Truly speaking, there is not single conception of the body in Indian medicine (Āyurveda), but a dominant one. (Wujastyk, forthcoming; Zimmemann, 2006) There is a bodily frame though which dosa-s, dhātu-s and mala-s flow. When a physician would examine a patient, he would go on reciting mnemonic verses related to the bodily organs. As a result, it appeared that there was no break. In this unique situation, anatomical knowledge seems to have been continuing since time immemorial. With this conception of the body and a unique theory of disease causation there was no need of dissection at all.

Let us now examine the etiopathogenetic process of a disease as conceived in Āyurveda. In Āyurveda, prodromes (pūrvarūpa) develop into full-fledged symptoms (rūpa). Secondary affections (upadrava) are consequences of the basic morbid process. At the end of this process recovery takes place or fatal signs (arista) appear, foreboding death. Each stage is characterized by a cluster of signs. In many cases the enumeration of these signs occurs in the form of verses, more easy to remember than statements in prose. (Meulenbeld, 2008: 612-613)

According to P. V. Sharma, the entire process of pathogenesis occurs through the following six stages: 1. Sañcaya (accumulation), 2. Prakopa (aggarvation), 3. Prasara (dissemination), 4. Sthānasamśraya (localization), 5. Vyakti (manifestation), and 6. Bheda (explosion). (Sharma, 1998: liii-lv) It is easily understandable that in this explanatory model of disease causation there is no need of anatomical knowledge or dissecting a body. It emanates from an entirely different conceptual framework.

At this juncture, it may be emphasized that till the sixteenth century Indian- European exchange or interaction of medical knowledge was at the level of herbal cures and simples. (Da Orta, 1895; Patterson, 2001) Da Orta was keener on knowing and acquiring Indian medical knowledge of treating the dreaded diseases like cholera. At the turn of the seventeenth century, when European physicians began to come to India it was almost a routine practice to deride at the utter lack of surgical and anatomical knowledge of Indian (especially Brahmin) practitioners. When by the later half of the sixteenth century learned physicians like Bernier and Fryer came to India, they came with knowledge of post-Vesalian knowledge of dissection and post-Harverian knowledge of circulation. Organ localization of disease and its cure principally by surgery were routinely done.

Tavernier, a self-taught physician, gives details of accurate blood-letting by a European surgeon Pitre de Lan to cure the then King of his chronic pain in the head. He commented, “as for surgery, the people of the country understand nothing about it.” (Tavernier, 1889: 302-303)

Although, to remember, unlike European surgery (emerging out of anatomical dissection and incessant scientific experimentations), Indian craft-based surgery was a family craft and not a thing of little importance.

Manucci was possibly the first traveller to give a somewhat detailed account of Indian rhinopalsty. “The surgeons belonging to the country cut the skin of the forehead above the eyebrows, and made it fall down over the wounds on the nose…In a short time the wounds heal up…I saw many persons with such noses, and they were not so disfigured as they would have been without any nose at all…” (Manucci, 1907: 301) Manucci, so to speak, does not specify who these surgeons were. However, so many accounts testify these people to be of low caste origin. Rhinoplasty, following Manucci’s observation, should be regarded as a regular practice in pre-colonial India as Manucci saw many people undergoing this operation. About a century later, Lambert observed, “An obstruction of the spleen…They make a small incision over the spleen, and then insert a long needle between the flesh and skin. From this incision, by sucking thro’ a horn pipe, they obtain a certain pinguous matter which resembles pus.” (Lambert, 1750: 99-100) An American doctor noted in 1856, “The blacksmith, with his tongs, serves as dentist, and the barber, with his razor, as surgeon; since these are the only persons supposed to have tools adapted to the practice of these professions.” (Bacheler, 1856: Emphasis added.)

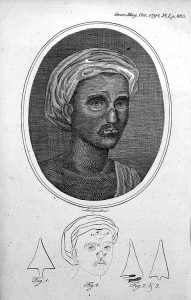

Against this backdrop, amidst rueful world of Indian surgical knowledge as noted by European travelers and physicians, appeared the news of Indian rhinoplasty. In a historical letter B(arak). L(ongmate) wrote to the editor of the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1794, “A friend ahs transmitted to me, from the East Indies, the following very curious, and, in Europe, I believe, unknown chirurgical operation, which has long been practiced in India with success: namely, affixing a new nose on a man’s face.” (B.L, 1794: 891- 892) A Maharatta (Marathi) by the name of Cowasjee (though, he seems to be a Parsee) was captured by Tipu Sultan’s soldiers who cut off his nose and one of his hands for his treachery. Cowasjee joined the Bombay Army near Srirangapatnam with a cut nose. He was a “pensioner of the Honourable East India Company.” A man “of the Brickmaker caste” near Poonah reconstructed the nose. “Two of the medical gentlemen, Mr. Thomas Cruso and Mr. James Trindlay (Findlay), of the Bombay presidency, have seen it performed…” Suśruta’s version has the skin flap being taken from the cheek; Cowasjee’s was taken from the forehead. Subsequently, the details and an engraving from the painting were reproduced in the October 1794 issue of the Gentleman’s Magazine of London. There were also drawings of the portrait of Cowasjee with his repaired nose.

B.L. commented, “This operation is not uncommon in India, and has been practiced from time immemorial.”

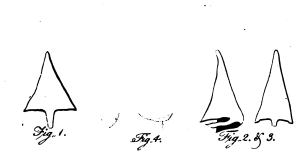

[Drawings of the skin flaps used in the operation – copied from the

Gentleman’s Magazine 1794.]

Other travellers also admired this expertise of Indian rhinoplasty. “I MUST by no means omit one branch of European surgery, that has of late been practised with great success by a Poonah artist, who has lately revived the Tailacotian art, differing only in the material…The sufferer applied to the great restorer of Hindoostan noses, and a new one, equal to all the uses of its predecessor, immediately rose in its place. It can sneeze smartly, distinguish good from bad smells, bear the most provoking lug, or being well blown without danger of falling into the handkerchief.” (Pennant, 1798: 237) Later medical authors also testify this excellence of Indian rhinoplasty. (Santoni-Rugiu and Sykes, 2007)

Cowasjee’s portrait with the reconstructed nose.

[Courtesy: Wellcome Library, London. L0017597 Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Indian method of the restoration of the nose by plastic surgery, from article by B.L. to Mr. Urban, concerning Cowasjee, a man who had his nose reconstructed with the aid of plastic surgery.

Line engraving 1794 By: Longmate From: Gentleman’s Magazine By: B.L. Published: 9th October 1794 Volume 64, part 2, facing page 883.]

Final Remarks

Eastern and Western medicine began with similar fusions of religion, spirituality, and science. Anatomists resorted to analogies of the universe to explain the body when superstitions surrounding death and the fate of the soul prevented closer observation through dissection. The dead body was venerated and paid due honour. Dissection was a taboo and social stigma. Like Āyurveda, there was greater emphasis on prognosis than diagnosis. We may find some similarities between Gilbertus Anglicus describing the thirteenth-century medicine in Europe and Āyurvedic practices. (Henderson, 1918) In classical European medicine, the existence of muscle in the modern sense was beyond physicians’ perception. It was rather flesh. In Hippocratic writings, the heart is actually an exceedingly strong muscle – “muscle, not in the sense of ‘tendon’ but of a compressed mass of a flesh…” (Lloyd, 1983: 348; Shanks, 2002; Matuk, 2006) There were even “anatomy riots” against grave robbing. All these phenomena and many more were rewritten into the forward moving victorious journey of modern medicine through institutionalization of dissection-based anatomical curricula, marvels of surgery through application of this knowledge of morbid anatomy and organ localization of disease, if not to say anything about therapeutic excellences. Detached clinical reasoning, having its premises on cadaveric knowledge (providing knowledge of the living) unwaveringly led to “necessary inhumanity”. It is reflected even in today’s medicine too. “Unfortunately, the “hidden curriculum” of contemporary medicine – especially the hurried, disease- centered, impersonal, high-throughput clinical years – still tends to undermine the best intentions of students and faculty members and the best interests of patients and families.” (Block and Billing, 2005: 1315)

In Indian context, it is better to say there was almost no anatomical practice at all. Hence, there was no question of the dead teaching the live. Consequently, “necessary inhumanity” is not the term suitable for this context. We do not even find any medical professionalism in European sense. Rather, Āyurveda constituted the matrix through which Indian subjectivity found its expression. The Āyurvedic assumption of the identity of body and nature is a logical consequence of the leitmotif of the Indian world view that asserts an underlying unity in the apparent multiformity of creation and strives for a transcendence of dualities, oppositions and contradictions. (Kakar, 1998: 219-251; Fabrega, 2009) In ancient India learning of grammar, logic and philosophy played very important role in the learning of medicine. As a result, at the epistemological level, one’s worldview was constructed along the line of predominant philosophy of the period. It is not comparable to the post-industrial, post-Enlightenment European society. Unlike Cartesian reasoning, Indian logic had “psychologized epistemology” in its core. In Caraka, “counter-demonstration is not a refutative enthymemes, for, nothing is refuted by it. It only establishes a proposition which happens to be logically contradictory to the thesis of the ‘demonstration’.” (Matilal, 1997: 3)

During the colonial period, especially after the reporting of successful rhinoplasty in the Gentleman’s Magazine, Indian medical knowledge and surgical crafts (like couching and lithotomy) were brought into the focus of mainstream of modern medicine, relativized and made marginal. Finally, the process of “colonizing the body” was set into motion with all vigour and maneuver.

To conclude, to de-essentialize this universalized epistemological and ontological preoccupations of “necessary inhumanity” we have to search for different epistemologies and corporeities. We find before us a corporeity which is marginalized as a consequence of the affirmation of new technologies. One has to emphasize that power-knowledge never succeeds in completely overcoming the body. The body always exceeds the power frame that attempts to control it. (Bhattacharya, 2004) This exceeding is possible partly because of the internal conflicts and contradictions among various discourses that attempt to control the body.

Reference

Abernethy, John. 1814. An Enquiry into the Probability and Rationality of Mr. Hunter’s Theory of Life; Being the Subject of the First Two Anatomical Lectures Delivered before the Royal College of Surgeons, of London. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees.

Āchārya, Jādavji Trikamji, ed. 2008. Suśrutasamhitā of Suśruta with the Nibandhasańgraha Commentary of Śrī Dalhanāchārya. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharati Prakashan.

Ackernecht, Erwin. 1967. Medicine at the Paris Hospital 1794-1848. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Apte, Vaman Shivram. 1985. The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Armstrong, David. 1999. Bodies of Knowledge/Knowledge of Bodies. In Reassessing Foucault, ed. Colin Jones and Roy Porter, 17-27. London, New York: Rutledge.

Arnold, David. 1993. Colonizing the Body: State Medicine and Epidemic Disease in Nineteenth-Century India. Berkley, London: University of California Press.

Ayeni and Barbara K. Dunn. 2002. The Human Cadaver in the Age of Biomedical Informatics. The Anatomical Record (New Anatomy) 269: 20-32.

Aziz, M. Ashraf, James C. Mckenzie, James S. Wilson, Robert S. Cowie, Sylvanus A. Bacheler, O. R. 1856. Hinduism and Christianity in Orissa: Containing a Brief Description of the Country, Religion, Manners and Customs, of the Hindus, and an Account of the Operations of the American Freewill Baptist Mission in Northern Orissa. Boston: Geo. C. Rand & Avery.

Bannister, H. Lawrence, Henry Gray and Peter Llewellyn Williams 1995. Gray’s Anatomy, 38th edn. Edinburgh, London: Churchill Livingstone.

Beclard, P. A. 1823. Additions to the general Anatomy of Xavier Bichat. Boston: Richardson and Lord.

Benner, Dagmar. 2009. Samskāras in Vāgbhata’s Astāńgahrdaysamhitā: garbhādhāna, rtusamgraha, pumsavana. In Mathematics and Medicine in Sanskrit, ed. Dominik Wujastyk, 119-133.

Bewell, Alan. 1999. Romanticism and Colonial Disease. Baltimore, London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bhattacharya, Jayanta. 2004. The Body: Epistemological Encounters in Colonial India. In Making Sense of Health, Illness and Disease, ed. Peter L. Twohig and Vera Kalitzkas, 23-54. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi.

Bichat, Xavier. 1809. Physiological Researches upon Life and Death, trns. Tobias Watkins. Philadelphia: Smith & Maxwell.

Bichat, Xavier. 1827. Pathological Anatomy, the Last Course, trns. Joseph Togno. Philadelphia: John Grigg.

Block, Susan D. and J. Andrew Billings. 2005. Learning from the Dying. New England Journal of Medicine 353: 1313-1315.

Brenner, M. J. 2000. Looking Back on the Millennium in Medicine. New England Journal of Medicine 342: 42-49.

Castiglioni, Arturo. 1947. A History of Medicine. 2nd edn. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. Chattopadhaya, Debiprasad. 1977. Science and Society in Ancient India. Calcutta: Research India Publications.

Da Orta, Garcia. 1895. Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs of India (New edition edited and annotated by the Conde de Ficalho), trans., Clements Markham. London: Henry Sotheran & Co.

Das, Rahul Peter. 1983. More on the Dissection of Cadavers in Ancient India. Ancient Science of Life 3 (1): 48.

Das, R. P. 2003. The Origin of the Life of a Human Being: Conception and the Female According to Ancient Indian Medical and Sexological Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Dasgpta, Surendranath. 1991. A History of Indian Philosophy, Vol. II. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Dyer, George S. M. and Mary E. L. Thorndike. 2000. Quidne Mortui Vivos Docent? The Evolving Purpose of Human Dissection in Medical Education. Academic Medicine 75: 969-979.

Edelstein, Ludwig. 1987. Ancient Medicine, ed. Owsei Temkin and C. Lillian Temkin. Baltimore, London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Elizondo-Omana, Rodrigo E., Santos Guzman-Lopez and Maria de Los Angeles Garcia- Rodriguez. 2005. Dissection as a Teaching Tool: Past, Present, and Future. The Anatomical Record (Part B: New Anatomist) 285 (1): 11-15.

Engler, Steven. 2003. “Science” vs. “Religion” in Classical Ayurveda. Numen 50 (4): 416-463.

Fabrega, Horacio Jr. 2009. History of Mental Illness in India: A Cultural Psychiatry Retrospective. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Fiser, I. and O. Fiserova. 1963. Dissection in Ancient India. In History and Culture of Ancient India (For the XXVI International Congress of Orientalists), ed. W. Ruben, V. Struve and G. Bongard-Levin, 306-328. Moscow: Oriental Literature Publishing House Foucault, Michael. 1994. The Birth of the Clinic: Archaeology of Medical Perception, trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Vintage Books.

French, Roger K. 1978. The thorax in history 4. Human dissection and anatomical progress. Thorax 33: 439-456.

French, Roger K. 1993. The Anatomical Tradition. In Companion Encyclopedia of the History of Medicine, ed. W. F. Bynum and Roy Porter, 81-101. London, New York: Routledge.

Gelfand, Toby. 1980. Professionalizing Modern Medicine: Paris Surgeons and Medical Science and Institutions in the 18th Century. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Gregory, S. Ryan and Thomas R. Cole. 2002. The Changing Role of Dissection in Medical Education. Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA). 287 (9): 1180- 1181.

Hannaway, Caroline and Anne La Berge, ed. 1999. Constructing Paris Medicine. Amsterdam, Atlanta, GA: Rodopi.

Harrison, Mark. 1999. Climates and Constitutions: Health, Race, Environment and British Imperialism in India 1600-1850. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Henderson, Henry E. 1918. Gilbertus Anglicus: Medicine of the Thirteenth Century. Ohio, Cleveland: Cleveland Medical Library Association.

Hoernle, A. F Rudolf. 1994. Studies in the Medicine of Ancient India. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

Jolly, Julius. 1977. Indian Medicine, trns. C. G. Kashikar. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal.

Kakar, Sudhir. 1998. Shamans, Mystics and Doctors: A Psychological Inquiry into India and its Healing Traditions. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Kellett, C. E. 1961. Sylvius and the Reform of Anatomy. Medical History 5 (2): 101-116. King, Lester S. and Marjorie C. Meehan. 1973. A history of the autopsy. A review. American Journal of Pathology 73, 2 (November 1973): 514-544.

Kunte, Anna Moresvara. 1902. Aṣṭāńgahṛdaya. Bombay: Nirnaya-Sagar Press. Kutumbiah, P. 1999. Ancient Indian Medicine. Chennai: Orient Longman.

La Berge, Anne. 1999. Dichotomy or Integration? Medical Microscopy and the Paris Clinical Tradition. In Constructing Paris Medicine, eds. Caroline Hannawya and Anne La Berge, 275-312. Clio Medica 50. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi.

Lambert, Claude-Francois. 1750. A Collection of Curious Observations on the Manners, Customs, Usages, different Languages, Government, mythology, Chronology, Ancient and Modern Geography, Ceremonies, Religion, Mechanics, Astronomy, Medicine, Physics, Natural History, Commerce, Arts, and Sciences, of the Several Nations of Asia, Africa, and America, trns. John Dunn, Vol. I. London: Printed for the Translator.

Leidy, Joseph. 1859. Lecture Introductory to the Course on Anatomy in the University of Pennsylvania for the Session 1858-59. Philadelphia: Collins.

Lloyd, G. E. R. ed. 1983. Hippocratic Writings. London: Penguin Classics.

L(ongmate), B(arak). 1794. Curious Chirurgical Operation. Gentleman’s Magazine 64 (ii): 891-892.

Manucci, Niccolao. 1907. Storia Da Mogor or Mughal India 1653-1708, Vol. II. trns. William Irvine. London: John Murray.

Matilal, Bimal Krishna. 1997. Logic, Language and Reality: Indian Philosophy and Contemporary Issues. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Matuk, Camillia. 2006. Seeing the Body: The Divergence of Ancient Chinese and Western Medical Illustration. Journal of Biocommunication 32 (1): 1-8.

Mazars, Guy. 2006. A Concise Introduction to Indian Medicine, trns. T. K. Gopalan. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

McLachlan, John C and Debra Patten. 2006. Anatomy teaching: ghosts of the past, present and future. Medical Education 40: 243–253.

Meulenbeld, G. Jan. 1999-2002. A History of Indian Medical Literature. Vol. IA, IB, IIA, IIB, and III. Groningen: Egbert Forsten.

Meulenbeld, G. Jan. 2008. The Mādhavanidāna: With ‘Madhukośa’, the Commentary by

Vijayarakṣita and Śrīkaṇṭhadatta (Chapters 1-10). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Monier-Wiliams, Monier. 2002. A Sanskrit-Englsih Dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Older, J. 2004. Anatomy: A must for teaching the next generation. The Surgeon: Journal of Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh and Ireland 2 (2): 79-90.

Osborne, Thomas. 1998. Medicine and ideology. Economy and Society 27 (2): 259-273. Otis, Laura. 1999. Membranes: Metaphors of Invasion in Nineteenth-Century Literature, Science, and Politics. Baltimore, London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Patterson, T. J. S. 2001. Indian and European practitioners of medicine from the sixteenth century. In Studies on Indian Medical History, ed., G. Jan Meulenbeld and Dominik Wujastyk, 111-120. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Pennant, Thomas. 1798. The View of Hindoostan, Vol. II. London: Henry Hughes. Prakash, Gyan. 2000. Another Reason: Science and the Imagination of Modern India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Pompilio, Carlos Eduardo, and Joaquim Edson Vieira. 2008. Sao Paulo Medical Journal 126 (2): 71-72.

Richardson, Ruth. 2000. Death, Dissection and the Destitute. Chicago, London: University of Chicago Press.

Rose, Nikolas. 1999. Medicine, History and the Present. In Reassessing Foucault: Power, Medicine and the Body, ed. Colin Jones and Roy Porter, 48-72. London and New York: Routledge.

Santoni-Rigiu, Paolo and Philip J. Sykes. 2007. A History of Plastic Surgery. Heidelberg and Berlin: Springer.

Sappol, Michael. 2002. A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America. Princeton, Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Sawday, Jonathan. 2006. The Body Emblazoned: Dissection and the human body in Renaissance culture. London, New York: Routledge.

Schaffer, Kitt. 2004. Teaching Anatomy in the Digital World. New England Journal of Medicine. 351: 1279-1281.

Shanks, David. 2002. Muscularity and the Western Medical Tradition. Hirundo: The McGill Journal of Classical Studies II: 58-81.

Sharma, P. V. 1998. Essentials of Āyurveda. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Sharma, Ram Sharan. 1996. Aspects of political ideas and institutions in ancient India. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Sigerist, Henry E. 1958. The Great Doctors: A Biographical History of Medicine. New York: Doubleday Anchor Books.

Sinh Jee, Bhagwat. 1896. A Short History of Aryan Medical Science. London: Macmillan & Co.

Souder, Elaine, RN, Tanya Laws Terry and Robert E. Mrak. 2003. Autopsy 101. Geriatric Nursing 24 (6): 330-337.

Stanley, Peter. 2003. For Fear of Pain: British Surgery, 1790-1850. Clio Medica 70. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi.

Tavernier, Jean-Baptiste. 1889. Travels in India, trans., Valentine Ball, Volume I. London: Macmillan & Co.

Turner, Bryan S. 2006. Body. Theory, Culture & Society 23: 223-226.

Warner, John Harley and Lawrence J. Rizzolo. 2006. Clinical Anatomy 19: 403-414. Wujastyk, Dominik. 1998. The Roots of Ayurveda: Selections from Sanskrit Medical Writings. New Delhi: Penguin Books India.

Wujastyk, Dominik. (Forthcoming). Interpreting the image of the human body in pre- modern India. International Journal of Hindu Studies.

Zimmermann, Francis. 1999. The Jungle and the Aroma of Meats: An Ecological Theme in Hindu Medicine. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

Zimmermann, Francis. 2006. The Conception of the Body in Ayurvedic Medicine: Humoral Theory and Perception. Retrieved January 26 2007, from http://philosophindia.fr/india/index.php?id=35. (Revised and published on the web in April 2006. An earlier version of this paper was published in 1983 from Heidelberg: Remarks on the conception of the body in Ayurvedic medicine, South Asian Digest of Regional Writing, 8 (1979 [actually 1983]), Sources of Illness and Healing in South Asian Regional Literatures, Heidelberg, University of Heidelberg: 10-26)

Zysk, Kenneth G. 1983. Some Observations on the Dissection of Cadavers in Ancient India. Ancient Science of Life 2 (4): 187-189.

Zysk, K. G. 2000. Ascetism and Healing in Ancient India: Medicine in the Buddhist Monastery. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

[This paper was published in Cultural Contours of History and Archaeology (in honour of Snehasiri Prof. P. Chenna Reddy and in 10 volumes, 11 parts), volume 8, eds. K. Krisnha Nail and E. Siva Nagi Reddy (Delhi: B. R. Publishing Corporation, 2015), 263- 280.]

* I deeply acknowledge my indebtedness to Rahul Peter Das, Domink Wujastyk and Geraldine Forbes. They have provided me with so many invaluable journals, books and other academic materials, which have facilitated this work.

Well written article

However, the discussion about “Indian” rhinoplasty is not complete

Susruta did not describe the forehead flap rhinoplasty but rather the cheek flap rhinoplasty an operation that is carried out even today

I can send you examples of Sushruta rhinoplasty technique – write on ghoshmm@gmail.com

Interesting article. Thank you.