Ever since the germ theory of disease was proved experimentally by Louis Pasteur two hundred years ago, the world has understood bacteria as the cause of numerous infections, many of them deadly. The insight led to the advent of medical principles and products – such as antibiotics- to cure these diseases and save thousands of human lives.

The germ theory was however also coloured by the imagination of the nineteenth century when – in the midst of the industrial revolution – the machine and the discipline of engineering were held as the highest achievements of humanity. So much so that the human body itself was considered a machine that could be repaired by doctors with the right tools, spare parts, detergents and lubricants.

The nineteenth century was also a time when rigid identities were being imposed on citizens in terms of their nationality, religion or ethnic status and the idea of ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ was being consolidated in popular understanding. This was extended to bacteria through the ‘war metaphor’ in medicine which perceived them as dangerous ‘outsiders’ – like invaders, trespassers or illegal migrants – to be ‘exterminated’ by all means. I don’t know why and this may be a bit unfair too but whenever I think of a doctor prescribing antibiotics needlessly I think of a lynch mob out to hang someone on mere suspicion of a crime.

So, what exactly is the problem with the war metaphor, which has been the dominant way of dealing with bacteria, viruses or other microbial parasites for over a century now?

- The war metaphor is based on a very mechanical understanding of how these invisible organisms operate. The higher the dosage of antibiotic used the higher the chance of eliminating all the infection-causing bacteria. The principle involved is the same as in Newtonian physics, greater the force used greater will be the momentum of whatever action is sought. While this borrowed metaphor from the world of Newtonian physics may have served the needs of dealing with infectious diseases in the past it has been a strategy with diminishing returns for many decades now. One of the main downsides of this approach for example is the emergence and rapid spread of antibiotic resistance around the globe over the last 80 years.

- In the war metaphor all bacteria are viewed as individual actors without a collective identity and as passive targets that can be eliminated or neutralised by bombarding them with antibiotics. As the late Israeli bio-physicist Eshel Ben Jacob showed in his work on bacterial intelligence, very large congregations of bacteria coordinate their actions through intricate signalling mechanisms and work in a way that is in the best interests of their entire group.

- Bacteria, like all forms of life, are very often guided in their actions and responses by non-linear processes. What that really means is that the path to understanding them, living with them or even taming them does not lie along any straight line but follows patterns that are as intricate as they are aesthetically beautiful.

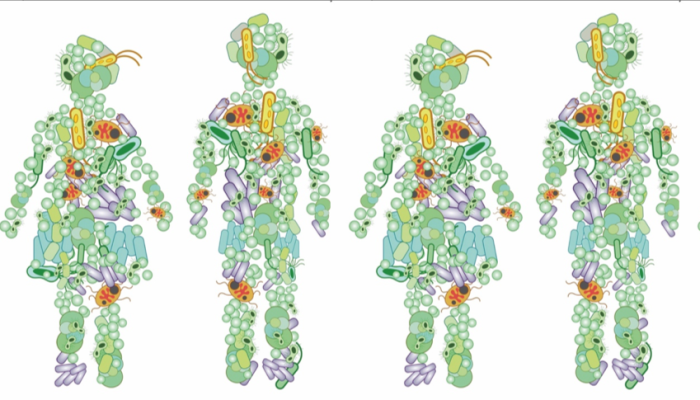

- What we also understand today is that there are no ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ when it comes to bacteria. New research in the past two decades has revealed the stunning scale and diversity of the bacterial world and in particular their crucial role in human survival. For example, the total microbial biomass in an average adult is approximately 0.2 kg and the microbiome today is considered another organ of our bodies.

- In fact, bacteria are part of an ancient and extremely rich ecosystem of organisms that are indispensable to all life on Planet Earth. It is bacteria that govern the most fundamental processes on our planet, from fixing nitrogen in the soil and recycling of organic waste to determining the composition of atmospheric gases to even the health trajectory of individual humans.

In this scenario of our rapidly changing understanding of the bacterial world, it is time to ask the question, whether infection, disease and antibiotic resistance are the only lenses through which we should perceive the bacterial world?

Could bacterial resistance – instead of being seen only as a threat- also offer us some lessons about adaptation and survival in the era of climate change? What are the processes and principles at work within the bacterial world that are worth emulating in our own collective behaviour as humans?

And strange as it may sound is it possible to stop fighting them perpetually and learn to ‘Dance with the Bacteria?

It is my contention that, done with great humility and wisdom, learning from bacteria – the oldest and most numerous organisms on our planet- can help the human species undo past mistakes and pave the way for a far more sustainable future. What are some of these lessons? This is not an exhaustive list I am attempting here but here are some possible things we can learn:

- Conserving diversity: More than any other factor it is the sheer genetic diversity of the bacterial world that allows resistance to emerge again and again when confronted with antibiotics. For humans societies the lesson is clear – the more diverse we are the greater the chance of our own survival as a species in the face of various calamities.

- Adapting to change: Bacteria have around for roughly 4 billion years on a planet that is 4.5 billion years old. They have not only survived the harshest temperature, weather, toxicity and abrupt shifts in environmental conditions but have time and again contributed to mitigating these factors and making them conducive to the flourishing of life. They have in other words shown phenomenal resilience faced with the toughest of challenges – a remarkable trait that again humans would do well to emulate.

- Working collectively: We now know that bacteria are living organisms which operate collectively in complex ways that are both dynamic as well as intelligent in their own way. What humans can certainly learn from bacterial behaviour is the importance of collectives and collective functioning – as the fate of individual humans is also deeply interconnected with that of all other humans and other forms of life on the planet.

- Balanced consumption: One of the interesting characteristics of many bacterial species studied is the way they conserve resources and never overconsume whatever is available to the point of complete exhaustion. We need to take from nature around us for our survival but the principle that we, as a species, need to learn from the bacteria, is to never take more than we can return to Mother Earth.

- Moving with ecological cycles: Through their recycling function, what bacteria reveal to us is that even after death the human body never perishes materially, except in its outer form and continues to play a role in the planetary ecosystem. Bacteria help complete the great ecological cycle of birth, growth and death that all of us humans are part of. Understanding these cycles is critical for us to make choices appropriate to different stages of these cycles and be in harmony with the great designs of nature that have evolved over millions of years.

What all this shows is that the war metaphor, that unfortunately still dominates our response to bacteria and bacterial resistance is hopelessly outdated and wrong. At the very least, it needs a serious course correction to acknowledge that bacteria dance to a different rhythm than the monotonous beat of marching drums and jackboots.

The metaphor of ‘dance’ and that of ‘Dancing with the Bacteria’ is one possible alternative to the one where war is seen as the only way forward. A dance does not imply a surrender of one dancer to the other or a domination either.

It is simply the art and science of moving together to a background music without stepping on each other’s toes. It calls upon the dancers to pay attention to history, tradition, culture the ambience, the mood and even the audience all at once without not skipping a single beat.

There is nothing mysterious about this at all. The dance is the metaphor also for all life as it has evolved over the millennia. We dance to negotiate our way through the ups and downs, open threats and secret joys of life all the time.

As health professionals, activists, indigenous communities and others we have to realize we have to learn ultimately to learn to Dance with the Bacteria. There is really no other way we can co-exist with both our grave problems as well as our wonderful synergies.