(Howrah Bridge in 1890s)

Preliminary Remarks

As is well known to scholars, historians and interested readers of the history of Howrah, its history dates back to 500 years or so and the place was earlier known as the Bengali kingdom Bhursut. I wish to draw attention to some of the historical facts of importance. Like any other places people and habitation were in presence in Howrah what is now called the twin city of Kolkata. L. S. S. O’Malley, one of the most authentic historians of Howrah in the early 20th century cautions us – “The history of Howrah, prior to the advent of European merchant adventurers, is practically unknown, and any attempt to trace it must necessarily lead along a wide and somewhat insecure track of conjecture.”[1]

However, Bipradasa Piplai’s Manasa Vijaya (edited by Sukumar Sen) is supposed to be written in 1495 A.D. and describes the voyage of Chand Sadagar from Burdwan to the sea. In this account, names like Ghusuri and Bator are found. The first mention of any place in the district by a European writer occurs in the journal of the Ventian Cesare Federici. His journal or travel account bears a very long name.[2] Federici visited the place in 1578. Regarding his account Donald Lach comments – “Like most itinerant merchants of the East, Fedrici eventually visited the emporiums at the mouths of the Ganges. From Orissa he was rowed along the shore and up the Ganges in large flat-bottomed boats which made their progress upriver with the incoming tide. Seagoing vessels, he indicates, are able to go upriver only to “Buttor” (Betor, near modern Howrah) where they unload and load at a temporary mart built of straw which is constructed and burned annually at the arrival and departure of the trading ships.”[3]

In Frederici’s account – “then we enter into the Riuer Gan¦ges: from the mouth of this Riuer, to a Citie called Satagan where the Marchants gather them selues together with their trade, are ••20. miles, which they rowe in 18. howers: with the increace of the water, in which Riuer it floweth and ebbeth as it dooth in the Themes, and when the ebbing water is come, they are not able to rowe against it, by rea∣son of the swiftnesse of the water, yet their Barkes be light and armed with oares, like to Foistes, yet they cannot pre∣uaile (Bazaras and Pauas are the names of the Barkes that they row in the Riuer Ganges) against that streame, but for refuge must make them fast to the banke of the riuer vntill the next flowing water, and they call these barkes Bazaras and Patuas: they row as wel as a Gallyot, or as wel as euer I haue séen any, a good tides rowing before you come to Satagan, you shall haue a place which is called Buttor, and from thence vpwardes the Shippes doo not goe, because that vpwards the Riuer is ve∣ry shallowe, and little water, euerye yéere at Buttor they make and vnmake a Village, with houses and shops, made of Strawe, and with all thinges necessary to their vses, and this village standeth as long as the shippes ride there, and depart for the Indies, and when they are departed, euery man goeth to his plotte of houses, and there setteth fier on* them, which thing made me to meruaile.”[4]

Next, we can examine Captain Alexander Hamilton’s account of the East Indies.[5] Hamilton writes – “On the other side of the River are Docks made for repairing and fitting their Ships Bottoms, and a pretty good Garden belonging to Armenians”.[6] We can deduce that small proto-industries were being built in Howrah during the mid-18th century. As a consequence, there must be regular incidents of casualties of Indian people working there. Moreover, it transpires that ships were coming to different areas of Howrah and so would be sailors coming there. Hamilton, in his sarcastic account also gives an account of a hospital in Calcutta – “The Company has a pretty good Hospital at Calcutta, where many go in to undergo the Penance of Physick, but few come out to give Account of its Operation.”[7] From this description the condition of medical service and expertise of the time becomes quite evident. If such was the case in Calcutta, we can surmise that how the situation in Howrah, related to health, medicine and healing, could be at that time.

Regarding “Docks made for repairing and fitting their Ships Bottoms” Moorhouse comments – “Note the precision – ‘ship’s bottoms’, not just ‘ships’, this is a seadog after all.”[8] Again, as Moorehouse shows that the East India Company (EIC) “had sent a deputation to Delhi, led by the merchant John Surman, to buy up another thirty-eight villages, including Howrah across the river”[9].

From another account it becomes evident that 5 villages were much coveted by the EIC. “The list of Towns ordered to be entered after the Consultation of May 4th 1714, being a list of Towns that East India Company already possessed round Calcutta, and of those they wished the Mogul (Emperor Farrukhsiyar) to grant them in his Phirmaund –

Towns Named Purgunnas

Salica (Salkia) Borow

Harirah (Howrah Borow

Cassundeah (Kasundia) Borow

Ramkissonpoor (Ramkrishnapur) Borow

Batter (Betore) Borow…”[10]

With these observations on how Howrah began to emerge as a commercial centre on the other side of the Ganges, we may now begin our journey to figure out health and healing conditions, otherwise medical history, of Howrah. I shall limit my paper to the period spanning the first quarter of the early 19th century to the mid-20th century or so.

Medicine and Public Health

To mention, in 1787 the Hooghly district was formed and in 1819 the whole of the present day Howrah district was added to it. The Howrah district was separated from the Hooghly district in 1843. On 1st May 1822 the Hooghly and Howrah Collectorate was entirely separated from Burdwan.[11]

From present perspective, “Howrah has a tropical climate. The summers here have a good deal of rainfall, while the winters have very little. This climate is considered to be Aw according to the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. The temperature here averages 26.0 °C | 78.8 °F. Precipitation here is about 1656 mm | 65.2 inch per year. Howrah is in the northern hemisphere. Summer begins at the end of June and ends in September. The months of summer are: June, July, August, and September. The best time to visit is February, March, October, and November.”[12]

But a large part Howrah of the period I’ll be dealing with was a marshy land and criss-crossed by many rivers. Drainage system was rudimentary. As a result a huge number of fever patients (to keep in mind, fever was then a blanket term under which most of the conditions causing fever were stacked into) and patients of diarrheal diseases were seen. O’Malley described the climate of Howrah in early 20th century as – “The climate of the district leaves much to be desired from an hygienic point of view. The land is low-lying, intersected by rivers and creeks, and studded with marshes, stagnant pools and silted-up river channels. Humidity is high, the rainfall is heavy, and the heat, though tempered to some extent by sea-breezes, is enervating.”[13]

Against this perspective, Howrah Seamen’s Hospital was established in 1824 (in some accounts the year of its establishment is taken as 1828) for the treatment of sick European seamen. There were definite terms for admission for officers as well as seamen. For officers, it was two rupees per day and for seamen one rupee per day for treatment at the hospital.[14] “The above charges include house-rent, attendance, clothing, bed clothes, board, medicines, and medical attendance.”[15] Next was established Howrah Native Hospital in 1828. The average number of patients received in the hospital was 3,500 and the average daily number of inmates fed and housed was 10. The hospital was capable of receiving 20 patients and more if necessary.[16]

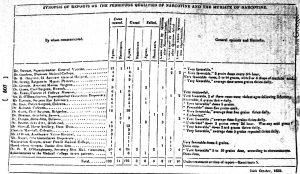

Howrah Seamen’s Hospital is important for another historical reason. Briefly speaking, most likely as a result of imperial conflict between colonial Indian government and Peru, there was embargo on importing Peruvian bark which was very much essential to procure quinine to treat various fevers in India. In the August (1838) meeting of Medical and Physical Society of Calcutta it was reported, “Dr. O’Shaughnessy read an extract from the last No. of Johnson’s Medico-Chronological Review, containing the important information, that the Peruvian Government had suspended the exportation of cinchona bark for a period of five years. Dr. O’Shaughnessy then laid before the Society the details of thirty-two cases of remittent and intermitant (sic) fevers treated by narcotine as a substitute for quinine, and of which thirty-one were cured.”[17] In the late 1830s, W. B. O’Shaughnessy made extensive experiments with his newly discovered drug narcotine, supposed to be a substitute of quinine, on patients in the laboratory of the CMC.[18] The trial of narcotine was also reported in an American journal under the title “On Narcotine as a substitute for Quinine in Intermittent Fever”.[19] Besides intermittent fever, the American journal reported, narcotine was also used in ague – “Dr. O’Shaughnessy added that, besides the sixty cases now recorded, more than 100 ague patients had been treated by his pupils and acquaintance with perfect success by this remedy.”[20] It was also further mentioned in the same journal that “In a subsequent number of the Indian journal, the following letter appears, addressed to Dr. O’Shaughnessy, by Mr. Green, Civil Surgeon, Howrah.”[21] The letter, reproduced in the American journal read thus, I have now employed the narcotine in sixteen cases of remittent fever, and such is my opinion of the efficacy of the remedy, that in instances of fever, intermittents and remittents, in ordinary healthy subjects, and in whom there is no complications of severe organic disease, I give it with the full expectation of arresting the next periodic return of the fever … I consider narcotine a more powerful antiperiodic than quinine. The remedy does not act silently … In short, even from my scanty experience, I consider the remedy an invaluable one.[22]

Narcotine, a cheaper substitute of quinine derived from opium freely available in Indian bazaars, was put into trial by O’Shaughnessy to treat various fevers. It was enthusiastically reported at the meetings of Medical and Physical Society of Calcutta. Thus the Howrah hospital was intertwined with a new experiment going on in CMC, which was also published in the most celebrated journal Lancet.[23]

(The fourth from the top is Dr. Green who took part in the trial of narcotine.)

In the London Medical Gazette an impressive report was published about Seamen’s Hospital. It read thus – “We have received a Report of the Seaman’s Hospital at Howrah (the Deptford of Calcutta), which gives satisfactory evidence of the value of this institution … It appears that this hospital appears was rendered necessary chiefly on account of the great distance of the General Hospital (of Calcutta) from the shipping, and from the great increase of the shipping frequenting the port of Calcutta … We trust that those who have influence upon the spot will perceive the necessity for maintaining an establishment which offers the advantage of being at all times prepared to give almost immediate medical aid to the sick sea man – a service which should never be permitted to depend upon any contingency.”[24]

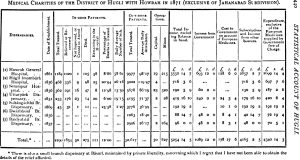

After the Seamen’s hospital, Howrah Native Hospital was formed in 1828, as already mentioned above. Next important European hospital was Howrah General Hospital established in 1861. About this hospital a report was published in the Indian Medical Gazette – “We have just received the Annual Report of this Institution for 1865. It is brief and modest, but very much to the point. We heartily congratulate the Committee and the Superintendent – Dr. Robert Bird – upon the success that has attended their endeavours. We find that during the last four years as many as 52,665 persons have been treated in the Howrah Hospital. During the past year there have been 777 European in-door, and 5,974 European out-door patients; whilst amongst Natives the corresponding figures have been 690 and 7,057. The deaths amongst the Europeans treated within the hospital amounted to 53; amongst Natives to 120. The number of seamen admitted is yearly increasing. In 1861 only 68 presented themselves; in 1865 there were no less than 368.”[25] There was an early report of cholera outbreak on board.[26] In another instance Harry Leach (1836–79), Resident Medical Officer on the Dreadnought hospital-ship, wrote that he had extensive experience of ‘‘scorbutic dysentery’’ at the European General Hospital at Howrah, Calcutta.[27]

The table below will reveal the importance of this hospital.[28]

The third quarter of the 19th century was devastated by fevers, especially ‘Burdwan Fever’, and other diseases. Hunter traced a number of causes for these conditions – (1) ‘use of bad water’, (2) ‘proximity to marshes’, (3) ‘vegetable decomposition’, (4) ‘defective conservancy and general insanitation’, (5) ‘defective drainage’, and (6) ‘poorness of food; bad hygienic conditions; excessive population’. Regarding silting of rivers and the bearings of this great subject, according to him, “on medicine have never been sufficiently studied … Given a stagnant, foul, shallow – it may be half-dried – waterway, one may generally expect to find in persons of those residing near it the distinctive cachexia loci (implying debility, sickness, spleen disease, and short life).”[29] He clearly stated – “The precise manner in which the unhealthy influence is generated and takes effect is yet unknown … The most important fact to remember is, that the remedy lies in effectual drainage, and in opening out either of dead rivers or of new channels of outflow … diminution of malarious disease has kept pace with the improvement of wet land.”[30] He suggested to be engaged in the question of drainage from an engineering point of view. Interestingly, it predates our present day public health engineering.[31]

Regarding ‘poorness of food; bad hygienic conditions; excessive population’, he pointed out a number of valid reasons for poor health conditions. Some of his observations were – (1) “the food consumed by the labouring population is insufficient to enable them to maintain themselves in a good hygienic condition, and to resist the climatic and other influences which excite to disease.”[32] (2) “A population of 940 per square mile is at the rate of 1.8 persons per cultivable acre; and 10 maunds or 800 ibs. Of rice would give an allowance of 1.2 lbs. per head per day, which is not sufficient for health.”[33] (3) “If the land cannot feed the population upon it, the remedy must lie either in reduction of population by emigration, or in increasing the productive powers of the soil by irrigation.”[34] It is important to note here that the traditional irrigation system of land practised by the peasantry was going to be replaced by the upcoming new irrigation system initiated by the British. It had two aspects – (a) humanitarian medical aspect to save the population from diseases and scarcity of food, and (b) to ensure the uninterrupted supply of cheap labour by sustaining at the minimal food acquisition level.

About diseases, Hunter put stress on ‘Burdwan Fever’ which was later diagnosed most likely to be a case of malignant malaria.[35] For example, the ravages of the epidemic were of astronomical level in one area which “contained 6961 souls before the outbreak, while in 1871 the population had decreased to 1739”[36]. Malaria was also associated with the railway lines then being constructed throughout India. At a much later date, formerly malariologist of Bengal-Nagpur Railway observed, “From the point of view of a Malariologist a railway is a Euclidean straight line. It might be thought of that any attempt to control malaria its route would be foredoomed to futility, unless powers of entry and work on surrounding property were granted. For this reason very little has in the past been attempted towards the control of malaria on railways.”[37]

As for ‘Relief Operations’, fever dispensaries were established at the larger centres of population, and an itinerant dispensary in the rural tracts, moving about from village to village, wherever the fever was severe. In 1869, 14 dispensaries were in operation, at which 48,744 persons received gratuitous medical aid, at a total cost of to Government £700 – “quinine, although it does much to check the accession of fever as an anti-periodic, is ill suited to the constitution of the ill-fed labouring population … the poorer classes are more amenable to treatment native than by European medicines.”[38]

Hunter then goes on to write about ‘Native Practitioners’. “The drugs in the pharmacopoeia of the kabiraj, or native medical practitioner, are derived alike from the gettable, animal, and mineral kingdoms … They are never produced from plants growing in jungly localities; and lucky days and hours are generally consulted by the kabiraj in collecting them … Urine is always given internally, as a laxative and tonic in spleen and liver diseases, leprosy, jaundice, and anasarca (generalized sweiing of the body)”.[39] Moreover, “The forms in which medicines are administered by native physicians are as powders, pills, infusions, and decoctions … The Hindu physicians compare the human body to a small universe, and maintain that, like the great universe, it has a creative, a preservative, and a destructive agency, in the shape of air, bile, and phlegm.”[40] It is interesting to note here that Hunter actually talks about two things – (1) macrocosmic-microcosmic balance, as was seen by Ayurvedic physicians, and (2) ‘humoral theory’ of disease causation which was abandoned by Western medicine after post-mortem dissection or autopsy was made a regular practice since late 18th century after the French Revolution.

In O’Malley’s account, there is mention of a few more deadly diseases – small-pox, cholera. O’Malley wrote regarding small-pox, “It was only in 1906 that the death-rate rose over one per mile, the incidence being highest in March and April. The town of Howrah suffered rather severely, having a death-rate of 3.43 per mile; but the village in the interior were comparatively immune.”[41]

Regarding cholera, O’Malley wrote, “Cholera is endemic in this district, the average death-rate during the years 1892-1896 being 3.73 per mille, while in 1907 the death-rate rose to 7.38 per mille, the maximum recorded … Of the rural areas Syampur thana suffers most, apparently on account of the difficulty of getting good drinking water after the rains. Howrah city returns the largest mortality, the reported death-rates in 1895 and 1896 being as high as 11.10 and 9.58 per mille respectively. In 1896 the new water-works were opened; and a supply of filtered water being available, the mortality dropped to 3.38 in 1897, and to 0.96 and 1.63 in the next two years.”[42] It is reported that in 1900 there was again a rise to 4.53 per mille, which was most likely connected to the large influx of coolies from Bihar. These coolies lived huddled together in insanitary ‘busties’, often did not drink pipe water, and ate coarsest kinds of grain.

Next the question of ‘Dysentery and diarrhoea’ was dealt with. But most of the deaths under diarrhoea and dysentery were those of old people. Then O’Malley described plague – first detected in 1900, and was not virulent by the time.[43]

O’Malley lets us know that vaccination against small-pox was compulsory in the two towns of Howrah and Bally. But the chief objectors were Musalmans and the lower-caste Hindus.[44] Regarding ‘Sanitation’ “the great sanitary need of the district of Howrah is the improvement of of drainage, filling up numerous unhealthy tanks, and the removal of excessive vegetation from the vicinity of dwelling-houses.”[45] During the time, drainage work was in progress in Howrah. But very little was done to fill up the large number of unhealthy tanks. Village sanitation was in its infancy. According to the Sanitary Commissioner, in 1899, “Howrah is without exception the dirtiest, most backward, and badly managed municipality I have seen.”[46] Finally, O’Malley observed, “It remains to note the improvements effected in meeting the most pressing sanitary wants of the town, viz., (1) a filtered water-supply; (2) a good drainage system; (3) an improvement of the bastis; (4) better conservancy arrangements for the disposal of filth and night-soil.”[47] In his observation, “Howrah is situated on comparatively high land on the west bank of the Hooghly … There is still no regular system of drainage. Most of the drains were kachcha drains without any proper alignment”[48].

Buckland wrote, “The drainage of land in Bengal is certainly one those problems nearly affecting the physical and material welfare of the people … malarious swamps formed by the silting up of streams. The natural drainage of the country being stopped, old beds of rivers becoming receptacles for stagnant water…”[49].

Some Eminent Doctors from Howrah

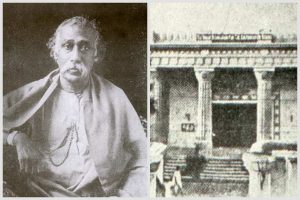

(Mahendralal Sarkar and IACS – the first building)

First among the most noted doctors is undoubtedly Dr. Mahendralal Sarkar – 2nd M.D. from Calcutta University (CU) and the founder of the Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (IACS) in 1876. Graduating from the CMC, he turned towards homeopathic practice in his later life. He passed out form the CMC in 1860 with excellent results. In 1868, he founded the journal Calcutta Journal of Medicine. Before the foundation of the IACS, he articulated his goals for such an institution – “We want an Institution which will combine the character, the scope and objects of the Royal Institute of London and of [the] British Association for the Advancement of Science. We want an Institution which shall be for the instruction of the masses, where lecture[s] on scientific subjects will be systematically delivered and not only [will] illustrative experiments [be] performed by the lecturers, but the audience should be invited and taught to perform [them] themselves.”[50]

With his great scientific spirit of original researches and inquiries in sciences, he categorically stated – “Nay, it is not right that we should continue to be not only the idle spectators of the wonders of science, but remain the unproductive recipients of the comforts daily heaped upon us as it were by its practical achievements. This last fact renders it imperative upon us all that we should be workers ourselves and help the onward march of humanity. We are so constituted that we must either go forward, or be driven backward, we cannot remain stationary. These is an immense difference between the civilized man and the man happening to live in civilized times; between the man of science and the man whom accident has placed in the era of science.”[51]

More poignantly, he, after the foundation of the IACS, clarified his position on scientific learning – “The very fact of being born at this stage of the world’s history is indeed in itself a privilege, but with such a privilege, to remain as ignorant as the man of the stone period, is not only a matter of unspeakable shame, but one of awful irresponsibility.”[52]

Dr. Panchanan Chatterjee, a surgeon from Bally, was internationally acclaimed. Another eminent physician-scientist was Dr. M. N. Dey. Dr. Jajneshwar Chatterjee, an obstetrician, was renowned all over India. ENT surgeon Dr. Satyaban Roy was nationally reputed. An eminent radiologist was Dr. Shambhu Mukherjee who started the course of radiology at CU. One of the founders of the psychology department of CU was Dr. S. N. Banerjee. The famous author of a book on physiology, Dr. Candi Charan Chatterjee, was also from Howrah. Dr. Tarit Kumar Ghosh of Howrah was the founder of the Bangur Institute of Neurology.[53] The founder of R G Kar Medical College Dr. Radha Gobinda Kar was a resident of Santragachi, Howrah.[54] Established in 1886 as the Calcutta School of Medicine, it had no affiliated hospital and practiced out of Mayo Hospital. In 1902, it moved to its own complex including a school building and hospital. In 1904, it merged with the National College of Physicians and Surgeons of Bengal and, after a period of further growth, was renamed as the Belgachia Medical College in 1916. The institution was given its current name on 12 May 1948 to honour Dr. Radha Govinda Kar who first conceived of it.

There were also good number of homeopaths and Ayurvedic physicians in Howrah. A detailed account can be found in Bandyopadhya and Santra’s books.[55] For precise and good discussion on the later of the 20th century Santra’s book is quite enlightening.

Many more names could be mentioned, but the limit of space forbids me from doing this. However, we can have glimpses of health, medicine, diseases, public health and different institutions affording services to alleviate the sufferings of the ailing population of Howrah of the time period mentioned this research paper can be had.

[1] L. S. S. O’Malley, Bengal District Gazetteers. Howrah (Calcutta: 1909), 17.

[2] The voyage and trauaile of M. Cæsar Frederick, merchant of Venice, into the East India, the Indies, and beyond the Indies. Wherein are contained very pleasant and rare matters, with the customes and rites of those countries. Also, heerein are discovered the merchandises and commodities of those countreyes, aswell the aboundaunce of goulde and siluer, as spices, drugges, pearles, and other jewelles. Written at sea in the Hercules of London: comming from Turkie, the 25. of March. 1588. For the profitabvle instruction of merchants and all other trauellers for their better direction and knowledge of those countreyes (London: Printed by Richard Iones and Edward White, 18. Iunij. 1588)

[3] Donlad F. Lach, Asia in the Making of Europe. Vol. 1.The Century of Discovery (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 473.

[4] Federici, ibid, pp. 22-23. I have retained the old English spellings as were in the 1588 edition, though difficult to understand at many places with our present understanding of the language. But it seems quite interesting.

[5] Alexander Hamilton, A New Account of the East Indies, Being the Observations and Remarks of Capt. Alexander Hamilton, Vol. II (Edinburgh: 1727).

[6] Ibid, 12.

[7] Ibid, 11. [Italics added]

[8] Geoffrey Moorhouse, Calcutta: The City Revealed (Penguin: 1994), 34.

[9] Ibid, 39.

[10] C. R. Wison, The Early Annals of the English in Bengal, Vol. 2 (London: 1900), 172.

[11] O’Malley, Bengal District Gazetteers. Howrah, 26-27.

[12] https://en.climate-data.org/asia/india/west-bengal/howrah-969448/

[13] O’Malley, idem, 52.

[14] The Bengal and Agra Annual Guide and Gazetteer for 1841, Vol. I, 2nd edition, p. 359.

[15] Ibid, 359.

[16] Ibid, 364.

[17] Calcutta Monthly Journal 1838, (August, No. XLV): 387-388 (387).

[18] “On Narcotine as a Substitute for Quinine in Intermittent Fever by Dr. O’Shaughnessy,” Lancet, 2 (1839), 606-607.

[19] “On Narcotine as a Substitute for Quinine in Intermittent Fever by Dr. O’Shaughnessy,” Lancet, July20 (1839): 606-607.

[20] “Materia Medica and General Therapeutics”, The American journal of the Medical Sciences XXV (1839): 191-205 (195).

[21] Ibid, 195.

[22] Ibid, 195.

[23] “On Narcotine as a Substitute for Quinine in Intermittent Fever by Dr. O’Shaughnessy,” Lancet, 2 (1839), 606-607.

[24] London Medical Gazette, Part 1 (May 1845): 379.

[25] “The Howrah General Hospital”, Indian Medical Gazette (July 1, 1866): 196.

[26] “Report of an Outbreak of Cholera on Board the Edith Moore”, Indian Medical Gazette (July 1, 1870): 155-156.

[27] G. C. Cook, “Scurvy in the British Mercantile Marine in the 19th century, and the contribution of the Seamen’s Hospital Society”, Postgrad Med J 2004;80:224–229.

[28] W. W. Hunter, A Statistical Account of Bengal, Vol. III, Districts of Midnapore and Hugli (including Howrah) (London: 1876), 440.

[29] Ibid, 423.

[30] Ibid, 423-424.

[31] Ibid, 426.

[32] Ibid, 430.

[33] Ibid, 431.

[34] Ibid, 432.[Italics added]

[35] Leonard Rogers, “The Lower Bengal (Burdwan) Epidemic Fever Reviewed and Compared with the Present Assam Epidemic Malarial Fever (Kala- Azar)”, Indian Medical Gazette (Nov. 1897): 401-408. Also see, U. N. Brahmachari, “On the Nature of the Epidemic Fever in Lower Bengal Commonly Known as Burdwan Fever. (1854-75.)”, Indian Medical Gazette (Sept. 1911): 340-343.

[36] Hunter, A Statistical Account of Bengal, idem, 436.

[37] R. Senior-White, “Studies in Malaria, as It Affects Indian Railways”, Indian Medical Gazette (Feb. 1928): 55-72.

[38] Hunter, A Statistical Account of Bengal, 435. [Italics added]

[39] Ibid, 438.

[40] Ibid, 438-439.

[41] O’Malley, idem, 56.

[42] Ibid, 56.

[43] Ibid, 58.

[44] Ibid, 59.

[45] Ibid, 59.

[46] Ibid, 60.

[47] Ibid, 61.

[48] Ibid, 62.

[49] C. E. Buckland, Bengal Under the Lieutenant-Governors, Vol. II (Calcutta: 1901), 610.

[50] Pratik Chakraborty, “Science, Morality, and Nationalism: The Multifaceted Project of Mahendra Lal Sircar”, Studies in History 2001; (17) 245-274. For detailed study on Mahendralal Sarkar and nationalist movement see, Jayanta Bhattacharya, Medical College er Itihas (2nd part, in Bengali, 2023).

[51] Mahendralal Sircar, “On the Necessity of National Support to an Institution for the Cultivation of Science,” in Collected Works of Mahendralal Sircar, Eugene Lafont and the Science Movement (1860-1910), ed. Arun Kumar Biswas (Kolkata: The Asiatic Society, 2003), 73-74. [Italics added]

[52] Sircar, Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science (1880), 76. Also see, John Bosco Lourdusamy, “The Indian Association for the Cultivation of Science: A Tortuous Tryst with ModernScience”, Journal of Science Education and Technology, Vol. 12, No. 4 (Dec., 2003), pp. 381-396. [Italics added]

[53] Hemendra Bandyopadhyay, Panchsho Bochhorer Howrah (in Bengali), 195-196.

[54] Ibid, 197.

[55] Hemendra Bandyopadhya, Howrah Zellar Itihas (in Bengali), 378-379. Also see, Tarapada Santra, Howrah (in Bengali), chapter 10 (pp. 49-52).

Wonderful article on establishment of medical infrastructures at Howrah and development of treatment of the European Seamen, factory workers, local people and slums developed by the factory workers.

I was more prompt in reading the account as I was born in 1952 in Howrah General Hospital and spent my early childhood near Howrah maidan.

Thank you, Dr Bhattacharya for presenting such a rich write up.

Fantastic

Very interesting essay. The comments and commentary on hygiene/sanitation/drainage system (or lack thereof) ring true even today.

I chanced upon your excellent article while Googling “Howrah Native Hospital” because I want to trace any family or address of D N Banerjea, Honorary Secretary of the HNH Committee in 1870. I have tried in vain to find a book by him published in 1871, on a completely non-medical subject: Is This Called Civilization? He was a catechist at the Howrah church and connected to Bantra Theatre. Did HNH have a library? If so, where did it go? Any other Howrah library that may have this book? As a senior citizen in south Kolkata, I have difficulties in travelling to Howrah without a personal contact to meet. Any help would be most welcome. Thank you.